Type the words, “Old habits …” into Google, and the search engine quickly adds, “die hard” and “are hard to break.” When I did it just now, these were followed by two song titles — one by Hank Williams Jr., the other by Mick Jagger — both dealing with letting go of past relationships. Alas, in love and life, breaking up is hard to do.

two song titles — one by Hank Williams Jr., the other by Mick Jagger — both dealing with letting go of past relationships. Alas, in love and life, breaking up is hard to do.

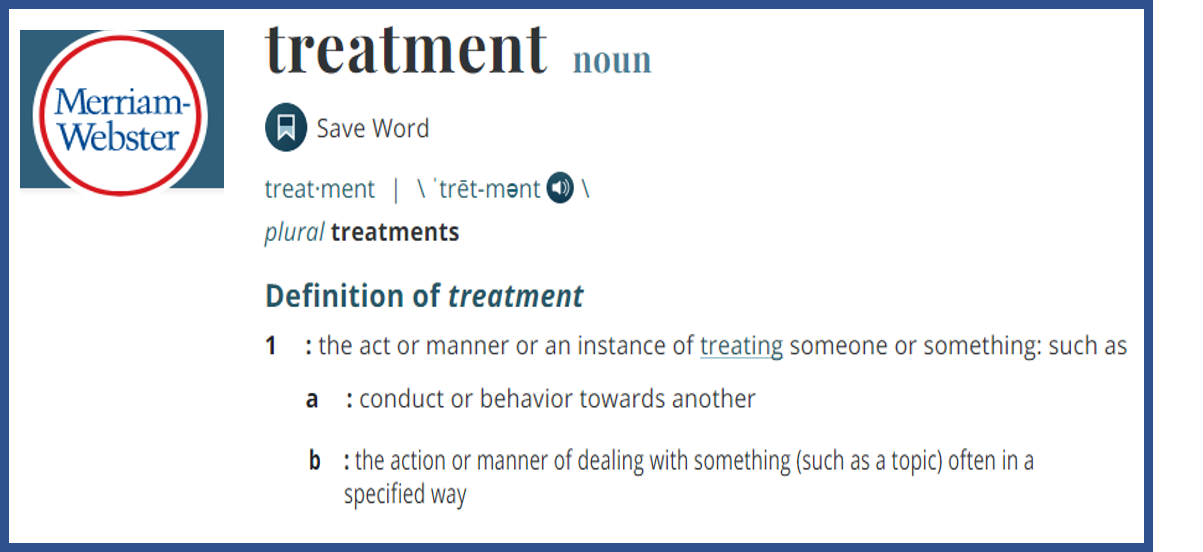

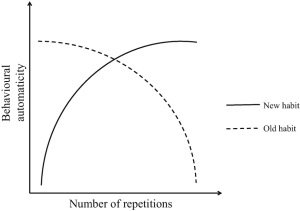

Like it or not, and despite our best intentions, we often end up returning to what we know. What are generally referred to as, “habits,” researchers in the field of expert performance label, “automaticity,” literally meaning thoughts and behaviors engaged in reflexively, involuntarily or unconsciously.

The evidence shows more than 40% of what we do on a daily basis is habitual in nature; that is, carried out while we’re thinking about something else (1). While such data might generate concern for most — “that’s a lot of acting without thinking” — the expertise literature indicates its absolutely essential to improving performance. Simply put, automaticity frees up our limited cognitive resources to focus on achieving performance objectives just beyond our current abilities — a process known as deliberate practice.

So, what’s your sense? How long does it typically take for new behaviors to be executed without a high degree cognitive effort?

Please jot down your answer before reading further.

Did you do it?

Now, before I provide a research-based answer, would you watch the video below? (It’s fun, I promise)

Having watched the video, would you care to change your answer? With a self-reported 5-minutes of practice per day, it took Destin 8 months to achieve automaticity on his “backwards bicycle.” His experience is far from unique. Turns out, most of us — like many of those in the video who confidently seated themselves on the bike, then failed — seriously underestimate the amount of time and effort required for establishing new, more effective habits.

Somehow, somewhere, sometime, someone asserted the road to automaticity was about 21 days (3). Research actually shows it takes, on average, three times as long and, in many instances, up to 8 months (2)! Does that latter figure sound familiar? Complicating such findings is the fact that many of the “habits” studied by researchers are relatively simple in nature (e.g., drinking a bottle of water with lunch, running 15 minutes after dinner). Imagine a more complex behavior, such as learning to respond empathically to the diverse clients presenting for psychotherapy — and, just so you know, soon to be published research shows such abilities do not improve with experience nor correlate with clinicians’ estimates of their ability — and the challenge involved in improving clinical performance becomes even more apparent.

And did I mention the sense of failure, even incompetence, that frequently accompanies attempts to establish new habits? It’s understandable why so many of our efforts to improve are short lived. Frankly, its far easier to see oneself as getting better than to actually do what’s necessary long enough to improve. The evidence, reviewed previously on this blog, documents as much (4).

In our latest book, Better Results (APA, 2020), we identify a series of evidence-based steps for helping therapists develop a sustainable deliberate practice plan. Known by the acronym A.R.P.S. (5), it includes:

In our latest book, Better Results (APA, 2020), we identify a series of evidence-based steps for helping therapists develop a sustainable deliberate practice plan. Known by the acronym A.R.P.S. (5), it includes:

- Automated: If you are asking yourself when, you likely never will.

- Reference point: Count your steps, not your achievements.

- Playful: Give in, let go, have fun.

- Support: Go alone and you won’t go far

Following these steps, we’ve found, helps clinicians maintain their momentum as they apply deliberate practice in their professional development efforts. To these, I add a precursor: Change your mindset. Yeah, I know, that results in C.A.R.P.S, meaning “to find fault or complain querulously or unreasonably; be niggling in criticizing minor errors,” but that’s precisely the point. Recalling that deliberate practice is about reaching for performance objectives just beyond our current abilities, think “small and continuous improvement” rather than “achieving proficiency and mastery.”

OK, that’s it for now.

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

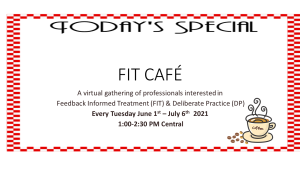

P.S.: Join me and my co-author Dr. Daryl Chow for our Online Deliberate Practice course. Designed for the busy professional, you learn at your own pace. Each week , you receive a bite-sized lesson. We provide ongoing support alongside a community of clinicians working to apply deliberate practice to their professional development. For more information or to register, click the icon below: