The use of routine outcome monitoring (ROM) is on the rise. In the United States and abroad, regulatory bodies are actually mandating the gathering of outcome data as the new “standard of care.”

The use of routine outcome monitoring (ROM) is on the rise. In the United States and abroad, regulatory bodies are actually mandating the gathering of outcome data as the new “standard of care.”

As agencies rush to implement–often at great cost in terms of time and money–the question remains: just how much does ROM contribute to improved retention and effectiveness?

Over 20 years ago, I began using outcome and alliance scales in my work as a therapist, asking clients at each visit to give me feedback about the qaulity of our relationship and their experience of progress. Eventually, together with colleagues, I developed two, brief measures: the Outcome and Session Rating Scales.

When studies using the scales began to appear in the literature, I was immediately concerned. In my opinion, the results were just “too good to be true.” First, the results were confounded by allegiance effects, having been done exclusively by people with a significant investment in the results. More to the point, however, I was worried that the studies focused on the measures rather than on therapists.

When studies using the scales began to appear in the literature, I was immediately concerned. In my opinion, the results were just “too good to be true.” First, the results were confounded by allegiance effects, having been done exclusively by people with a significant investment in the results. More to the point, however, I was worried that the studies focused on the measures rather than on therapists.

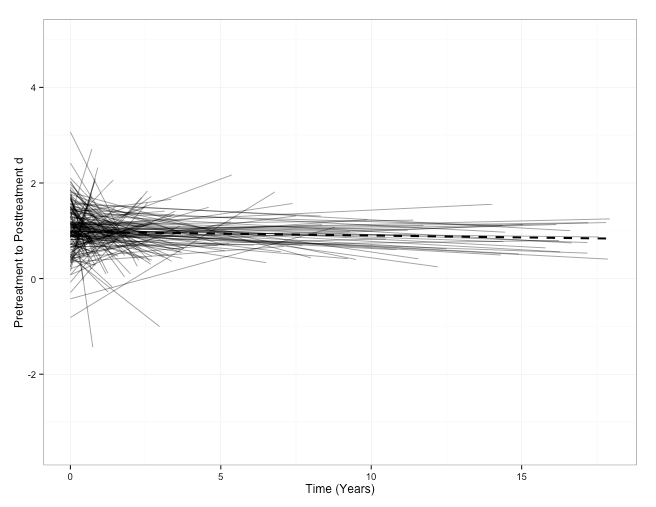

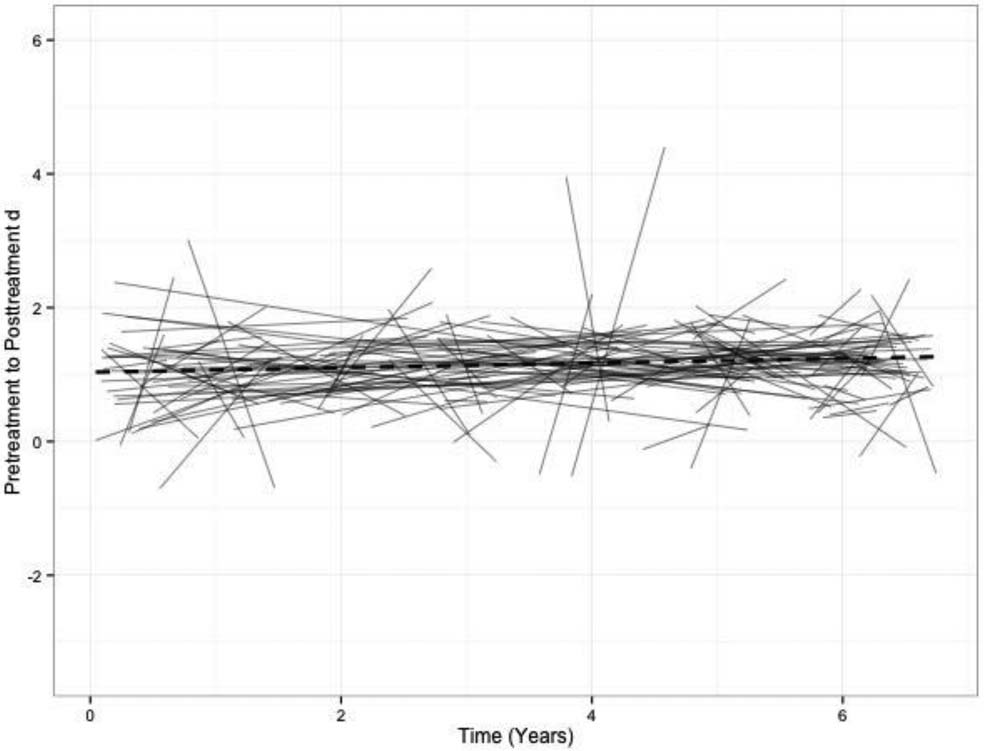

Soon, as I predicted, other studies appeared with far more modest results. And now, a meta-analysis of all studies using the ORS and SRS has been published, confirming that routinely measuring performance, improves outcome but not as much as reported in the original studies (viz., .27 versus .50).

For those involved in and advocating FIT (Feedback-Informed Treatment), this is an IMPORTANT study. It makes clear that when working feedback-informed, improving effectiveness requires more than the use of two measures. Indeed, it’s not really about the measures at all. Rather, it’s about therapists using feedback to identify opportunities for their own professional development.

For those involved in and advocating FIT (Feedback-Informed Treatment), this is an IMPORTANT study. It makes clear that when working feedback-informed, improving effectiveness requires more than the use of two measures. Indeed, it’s not really about the measures at all. Rather, it’s about therapists using feedback to identify opportunities for their own professional development.

As my colleague and fellow psychologist, Birgit Valla, is fond of saying, “A stopwatch will not make you a better runner. It’s not about the clock. It’s how you use the information to identify small, specific aspects of your performance that could be improved and then practicing.”

That’s what the team at ICCE and I have been exploring these past 7 years. The latest article summarizing that research was published just this week.

All the best,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

P.S.: Registration for the Spring Intensives is open. Click on the links below to reserve your spot!

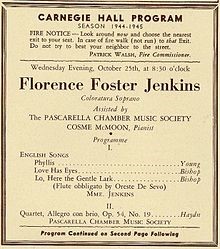

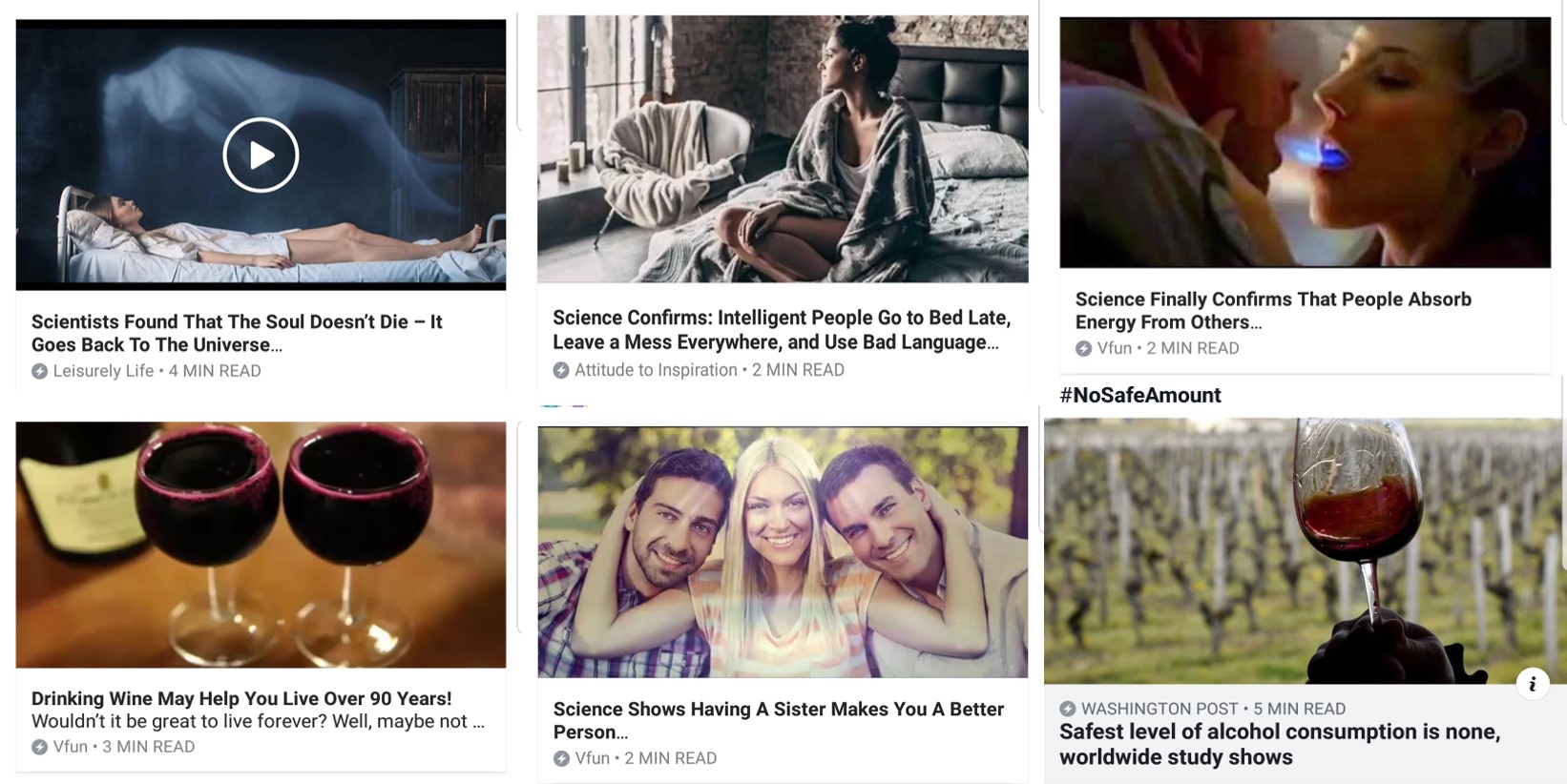

ose not to go to psychotherapy because they are busy doing something else–consulting psychics, mediums, and other spiritual advisers–forms of healing that are a better fit with their beliefs, that “sing to their souls.”

ose not to go to psychotherapy because they are busy doing something else–consulting psychics, mediums, and other spiritual advisers–forms of healing that are a better fit with their beliefs, that “sing to their souls.”

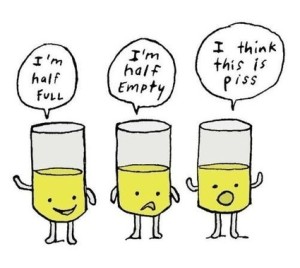

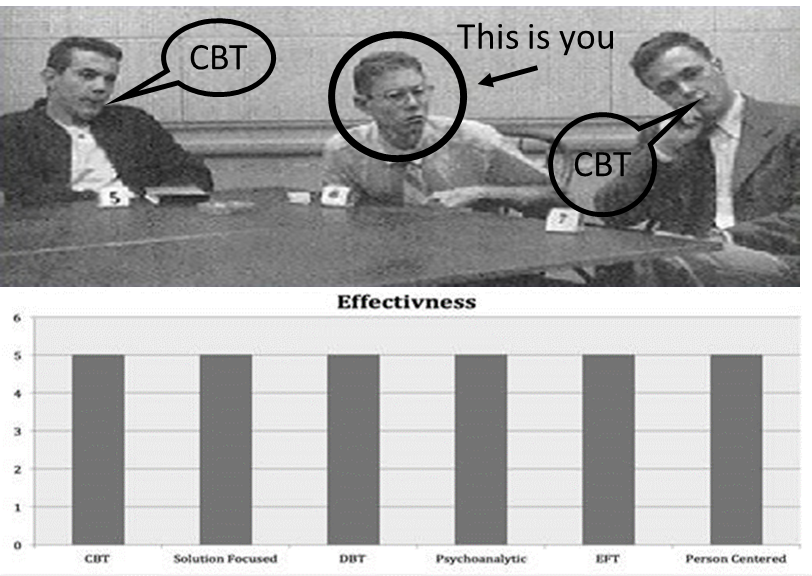

associated with self-assessment, we actively work to limit information that conflicts with how we prefer to see ourselves (e.g., capable versus incompetent, perceptive versus obtuse, intuitive versus plodding, effective versus ineffective, etc.).

associated with self-assessment, we actively work to limit information that conflicts with how we prefer to see ourselves (e.g., capable versus incompetent, perceptive versus obtuse, intuitive versus plodding, effective versus ineffective, etc.).

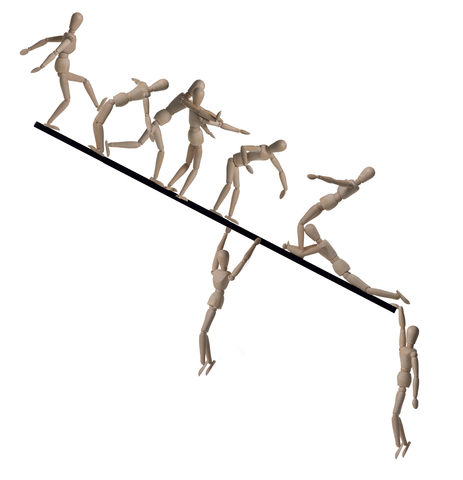

It’s not a steep slope, to be sure. It is slow and gradual, like a leak in a bicycle tire. Most problematically, other research shows, it’s also imperceptible. Indeed, as experience in the field grows, clinician-confidence increases, leading most to see themselves as more effective than their results actually indicate.

It’s not a steep slope, to be sure. It is slow and gradual, like a leak in a bicycle tire. Most problematically, other research shows, it’s also imperceptible. Indeed, as experience in the field grows, clinician-confidence increases, leading most to see themselves as more effective than their results actually indicate.

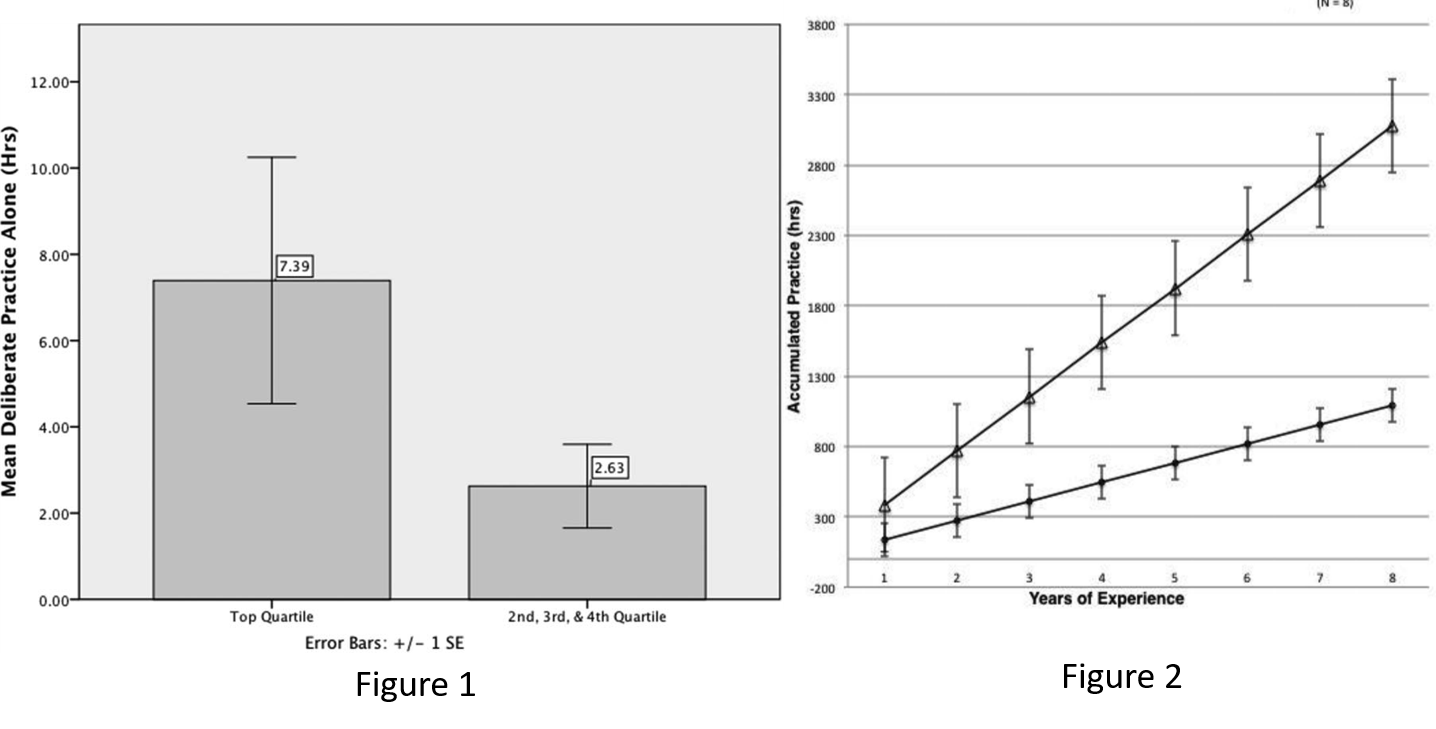

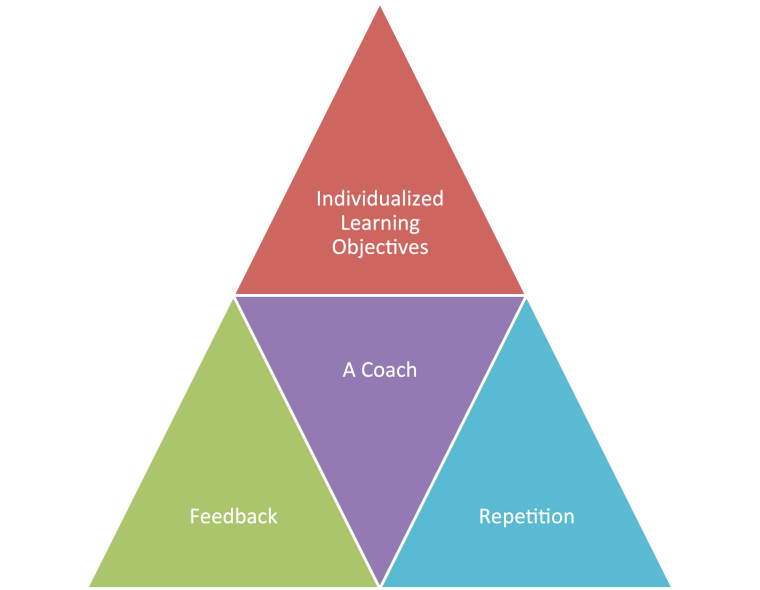

For the last several years, I’ve been advocating deliberate practice (DP)—conscious and purposeful effort aimed at improving specific aspects of an individual’s performance. DP contains four essential ingredients:

For the last several years, I’ve been advocating deliberate practice (DP)—conscious and purposeful effort aimed at improving specific aspects of an individual’s performance. DP contains four essential ingredients: