Being a mental health professional is a lot like being a parent.

Please read that last statement carefully before drawing any conclusions!

I did not say mental health services are similar to parenting. Rather, despite their best efforts, therapists, like parents, routinely feel they fall short of their hopes and objectives. To be sure, research shows both enjoy their respective roles (1, 2). That said, they frequently are left with the sense that no matter how much they do, its never good enough. A recent poll found, for example 60% parents feel they fail their children in first years of life. And given the relatively high level of turnover on a typical clinician’s caseload — with a worldwide average of 5 to 6 sessions — what is therapy if not a kind of Goundhog Day repetition of being a new parent?

For therapists, such feelings are compounded by the number of clients who, without notice or warning, stop coming to treatment. Besides the obvious impact on productivity and income, the evidence shows such unplanned endings negatively impact clinicians’ self worth, ranking third among the top 25 most stressful client behaviors (3, p. 15).

Recent, large scale meta-analytic studies indicate one in five, or 20% (4) of clients, dropout of care — a figure that is slightly higher for adolescents and children (5). However, when defined as “clients who discontinue unilaterally without experiencing a reliable or clinically significant improvement in the problem that originally led them to seek treatment,” the rate is much higher (6)!

Feeling “not good enough” yet?

By the way, if you are thinking, “that’s not true of my caseload as hardly any of the people I see, dropout” or “my success rate is much higher than the figure just cited,” recall that parent who always acts as though their child is the cutest, smartest or most talented in class. Besides such behavior being unbecoming, it often displays a lack of awareness of the facts.

By the way, if you are thinking, “that’s not true of my caseload as hardly any of the people I see, dropout” or “my success rate is much higher than the figure just cited,” recall that parent who always acts as though their child is the cutest, smartest or most talented in class. Besides such behavior being unbecoming, it often displays a lack of awareness of the facts.

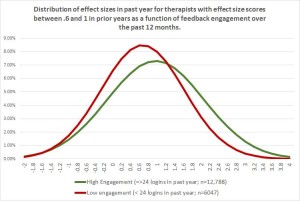

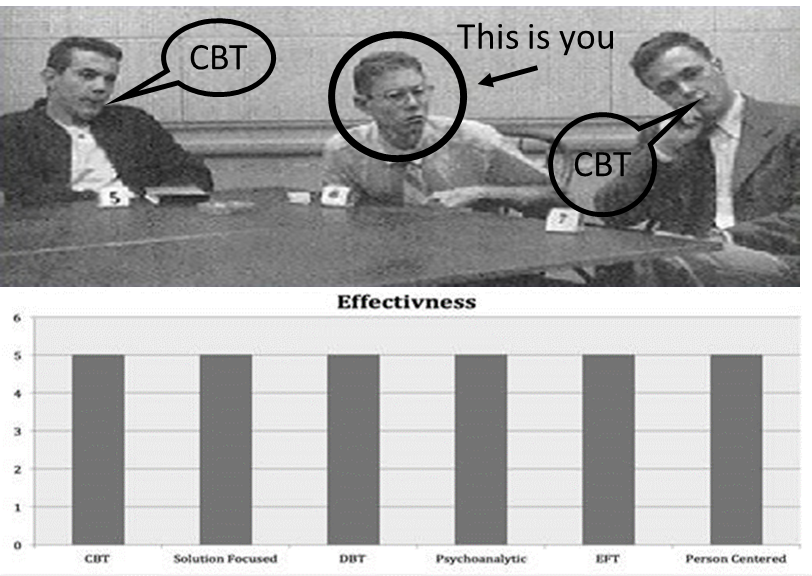

So, turning to the evidence, data indicate therapists routinely overestimate their effectiveness, with a staggering 96% ranking their outcomes “above average (7)!” And while the same “rose colored glasses” may cause us to underestimate the number of clients who terminate without notice, a more troubling reality may be the relatively large number who don’t dropout despite experiencing no measurable benefit from our work with them– up to 25%, research suggests.

What to do?

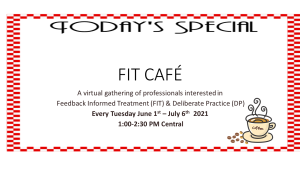

As author Alex Dumas once famously observed, “Nothing succeeds like success.” And when it comes addressing dropout, a recent, independent meta-analysis of 58 studies involving nearly 22,000 clients found Feedback-Informed Treatment (FIT) resulted in a 15% reduction in the number people who end psychotherapy without benefit (8). The same study — and another recent one (9) –documented FIT helps therapists respond more effectively to clients most at risk of staying for extended periods of time without benefit.

Will FIT prevent you from ever feeling “not good enough” again? Probably not. But as most parents with grown children say, “looking back, it was worth it.”

OK, that’s it for now,

Scott

Scott D. Miller Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

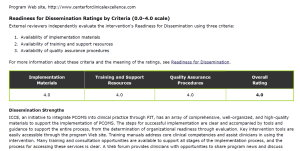

P.S.: If you are looking for support with your implementation of Feedback-Informed Treatment in your practice or agency, join colleagues from around the world in our upcoming online trainings.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)