I remember exactly where I was on April 4th, 1968 — in a pool doing laps. I was a junior member of my hometown’s swim team. I’d barely started when the coach blew his whistle calling the practice to an abrupt halt. As we toweled off, he told us something terrible had happened. It was first time I recall hearing the name, Martin Luther King, Jr..

I remember exactly where I was on April 4th, 1968 — in a pool doing laps. I was a junior member of my hometown’s swim team. I’d barely started when the coach blew his whistle calling the practice to an abrupt halt. As we toweled off, he told us something terrible had happened. It was first time I recall hearing the name, Martin Luther King, Jr..

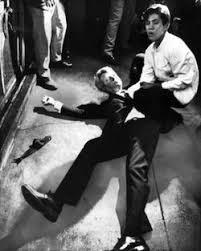

If I close my eyes, I can easily call up other, vivid memories of traumatic, culture-changing events. The death of Robert Kennedy. The Challenger explosion. The attack on the World Trade Center. And now, only slightly more than half way through the present year, many more. The first days of the outbreak and lockdown. The running tally of deaths on the nightly news. The lines of people at our local foodbanks. The images of George Floyd being killed, and weeks of protests against racism and inequality that have followed.

Then and now, I struggle with a stark choice; specifically, to connect or disconnect with events as they unfold. After all, so much is happening in the  world and I only have so much bandwidth — and as a person with many advantages, I can disconnect with little real consequence to the well-being of myself and my family.

world and I only have so much bandwidth — and as a person with many advantages, I can disconnect with little real consequence to the well-being of myself and my family.

In the end, however, I feel ethically compelled to connect, listen, or perhaps more accurately state, hear people — not because I see myself as knowing what to do, but rather because I want to understand if and how I can be helpful.

So, what does the research indicate?

When I was in graduate school, human diversity was treated in what might be called, “the chapter approach.” Here’s what the field knows about men, for instance, with another on women, African-Americans, Latinos, and so on. This approach can be directly traced to social, historical, and political events beginning in the 1960’s, and a then growing awareness of the lack of attention paid to diversity in the field of mental health– in particular, culture, race, religion, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, etc.

For several decades, researchers have built on this framework, developing and testing what have come to be known as “culturally adapted” psychological treatments (e.g., CBT for Latina Women or people of Asian heritage). Despite years of effort, including scores of randomized trails and meta-analyses, experts conclude, “Current evidence does not offer a solution to the issue of which components of cultural adaptation are effective, for what population, and whether cultural adaptation works better than noncultural adaption” (1).

Part of the problem with this approach is the sheer number of possible adaptations quickly becomes unmanageable. To illustrate, in developing a culturally adapted psychotherapy, where adjustments are made along only 4 of the 13 officially identified dimensions of diversity, a total of 715 different ways exist to adapt service delivery to fit the individual. Obviously, any approach that results in so many variations is absurd, making it impossible to apply in the real world and risking being nothing more than window dressing — a kind of superficial “gift wrapping” that conceals more than it helps to reveal the identities and objectives of the participants. More importantly, however, is that the current approach makes a priori decisions about which dimensions are most important to consider when planning and delivering treatment.

Part of the problem with this approach is the sheer number of possible adaptations quickly becomes unmanageable. To illustrate, in developing a culturally adapted psychotherapy, where adjustments are made along only 4 of the 13 officially identified dimensions of diversity, a total of 715 different ways exist to adapt service delivery to fit the individual. Obviously, any approach that results in so many variations is absurd, making it impossible to apply in the real world and risking being nothing more than window dressing — a kind of superficial “gift wrapping” that conceals more than it helps to reveal the identities and objectives of the participants. More importantly, however, is that the current approach makes a priori decisions about which dimensions are most important to consider when planning and delivering treatment.

What then are therapists who wish to connect more effectively with a broad and diverse clientele to do? Research makes clear when practitioners are open to exploring clients’ values, background, and culture, good results follow. Such evidence suggests, in place of competence (i.e., achieving a certain level of pre-determined knowledge about and skills for working with various cultural groups), its better to have an orientation to treatment that enables practitioners to attend to and integrate cultural dynamics as they naturally occur in the therapy process.

One of the lead researchers on multicultural orientation is Professor Jesse Owen at the University of Denver. Together with a team of investigators, he’s identified three core principles that both encompass and can guide a therapist’s attitudes, in-and-between session actions, and personal reactions regarding the role of culture in therapy. Interestingly, much of what he and the group have discovered fits with what my colleagues and I have been learning from our study of highly effective psychotherapists. I won’t give it away here. You can watch the interview yourself.

OK. That’s it for now. Please let me know your thoughts.

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Leave a Reply