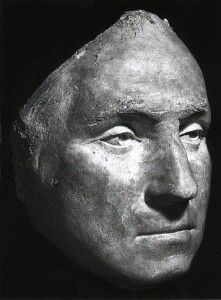

Here’s an interesting dilemma. In December 1799, three physicians were summoned to the Mount Vernon estate to treat the former first president of the United States for a sore throat. The accepted therapy of the day was administered skillfully and competently multiple times. Several hours later, the president was dead. Historians agree George Washington likely did not die of whatever illness he had, but rather from the care he received killed him. The intervention, of course, was bloodletting — the chief tool of which remains the title of one of medicine’s leading research journals (i.e., The Lancet [Flexner 1974]).

Here’s an interesting dilemma. In December 1799, three physicians were summoned to the Mount Vernon estate to treat the former first president of the United States for a sore throat. The accepted therapy of the day was administered skillfully and competently multiple times. Several hours later, the president was dead. Historians agree George Washington likely did not die of whatever illness he had, but rather from the care he received killed him. The intervention, of course, was bloodletting — the chief tool of which remains the title of one of medicine’s leading research journals (i.e., The Lancet [Flexner 1974]).

The question is, did Washington’s physicians act ethically?

According to the ethical codes of the four largest mental health provider organizations in the United States, the answer is an unsatisfying and deeply disconcerting, “yes.” Standard 2.01 of the Ethical Principles of Psychologists (APA 2017), for example, merely requires practitioners “provide services … with populations and in areas … within the boundaries of their competence, based on their education, training, supervised experience, consultation, study, or professional expertise” — conditions easily met by Washington’s physicians.

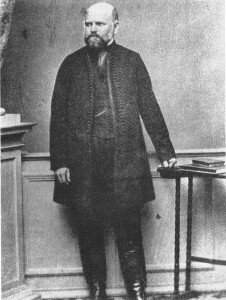

Before objecting that professionals should not be held accountable for standards of care yet to be developed, vetted by science, and  accepted by peers and regulatory bodies, consider another historical example. The year is 1846. Hungarian-born physician Ignaz Semmelweis is in his first month of employment at Vienna General Hospital when he notices a troublingly high death rate among women giving birth in the obstetrics ward. Indeed, with rates of 25 to 30 percent many expectant mothers prefer to give birth in the street rather than the clinic.

accepted by peers and regulatory bodies, consider another historical example. The year is 1846. Hungarian-born physician Ignaz Semmelweis is in his first month of employment at Vienna General Hospital when he notices a troublingly high death rate among women giving birth in the obstetrics ward. Indeed, with rates of 25 to 30 percent many expectant mothers prefer to give birth in the street rather than the clinic.

Medical science at the time attributes the problem to “miasma,” an invisible, poisonous gas believed responsible for a variety of illnesses. Having noticed that midwives have a rate 6 times lower than physicians, Semmelweis concludes his colleagues contact with dead bodies is somehow involved and orders them to wash their hands prior to interacting with expectant mothers. The mortality rate on the maternity warm immediately plummets landing at the same level as that of midwives.

Nowadays, of course, handwashing is a “best practice,” supported by a century of scientific evidence. During Semmelweis’s day, such data was not available. His was merely a hunch—one which, by the way, fell outside the boundaries of then current medical standards, his professional experience, education, and training. What’s more, he continued to promote the practice even after it was deemed unscientific by his peers and the broader professional community.

Returning to the earlier question, did Semmelweis act ethically? The answer, according to the field’s current ethical codes, would be “no.”

It’s hard to defend a standard that deems a practitioner who competently delivers an unhelpful, even deadly service (e.g., Washington’s physicians) ethically superior to one who is actually helpful but working beyond the limits of their education, training, supervised experience, consultation, study or professional expertise” (e.g., Semmelweis). And yet, that is precisely what the competence criterion in the current ethical codes of mental health provider organizations does.

It’s hard to defend a standard that deems a practitioner who competently delivers an unhelpful, even deadly service (e.g., Washington’s physicians) ethically superior to one who is actually helpful but working beyond the limits of their education, training, supervised experience, consultation, study or professional expertise” (e.g., Semmelweis). And yet, that is precisely what the competence criterion in the current ethical codes of mental health provider organizations does.

What alternatives exist? Adopting a standard of “working within and continually to extend the field’s and one’s own level of effectiveness” would achieve what the current criterion has failed to deliver: protecting the public welfare while facilitating ongoing improvement in the results of clinical services. It would also free therapists to use their creativity as well as take advantage of ideas from a variety of healing traditions.

But how?

Together with my colleagues Joshua Madsen and Mark Hubble, we lay out the details in a new chapter published this month in The Oxford Handbook of Psychotherapy Ethics. I’m hoping you’ll be interested in reading it.

Click here or email at scottdmiller@talkingcure.com if you’d like a copy.

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Leave a Reply