I’m sure you’ve heard it repeated many times:

I’m sure you’ve heard it repeated many times:

The term, “evidence-based practice” refers to specific treatment approaches which have been tested in research and found to be effective;

CBT is the most effective form of psychotherapy for anxiety and depression;

Neuroscience has added valuable insights to the practice of psychotherapy in addition to establishing the neurological basis for many mental illnesses;

Training in trauma-informed treatments (EMDR, Exposure, CRT) improves effectiveness;

Adding mindfulness-based interventions to psychotherapy improves the outcome of psychotherapy;

Clinical supervision and personal therapy enhance clinicians’ ability to engage and help.

Only one problem: none of the foregoing statements are true. Taking each in turn:

- As I related in detail in a blogpost some six years ago, evidence-based practice has nothing to do with specific treatment approaches. The phrase is better thought of as a verb, not a noun. According to the American Psychological Association and Institute of Medicine, there are three components: (1) the best evidence; in combination with (2) individual clinical expertise; and consistent with (3) patient values and expectations. Any presenter who says otherwise is selling something.

- CBT is certainly the most tested treatment approach — the one employed most often in randomized controlled trials (aka, RCT’s). That said, studies which compare the approach with other methods find all therapeutic methods work equally well across a wide range of diagnoses and presenting complaints.

- When it comes to neuroscience, a picture is apparently worth more than 1,000’s of studies. On the lecture circuit, mental illness is routinely linked to the volume, structure, and function of the hippocampus and amygdala. And yet, a recent review compared such claims to 19th-century phrenology. More to the point, no studies show that so-called, “neurologically-informed” treatment approaches improve outcome over and above traditional psychotherapy (Thanks to editor Paul Fidalgo for making this normally paywalled article available).

- When I surveyed clinicians recently about the most popular subjects at continuing education workshops, trauma came in first place. Despite widespread belief to the contrary, there is no evidence that learning a “trauma-informed” improves a clinician’s effectiveness. More, consistent with the second bullet point about CBT, such approaches have not shown to produce better results than any other therapeutic method.

- Next to trauma, the hottest topic on the lecture circuit is mindfulness. What do the data say? The latest meta-analysis found such interventions offer no advantage over other approaches.

- The evidence clearly shows clinicians value supervision. In large, longitudinal studies, it is consistently listed in the top three, most influential experiences for learning psychotherapy. And yet, research fails to provide any evidence that supervision contributes to improved outcomes.

Are you surprised? If so, you are not alone.

The evidence notwithstanding, the important question is why these beliefs persist?

According to the research, a part of the answer is, repetition. Hear something often enough and eventually you adjust your “truth bar” — what you accept as “accepted” or established, settled fact. Of course, advertisers, propagandists and politicians have known this for generations — paying big bucks to have their message repeated over and over.

For a long while, researchers believed the “illusory truth effect,” as it has been termed, was limited to ambiguous statements; that is, items not easily checked or open to more than one interpretation. A recent study, however, shows repetition increases acceptance/belief of false statements even when they are unambiguous and simple- to-verify. Frightening to say the least.

A perfect example is the first item on the list above: evidence-based practice refers to specific treatment approaches which have been tested in research and found to be effective. Type the term into Google, and one of the FIRST hits you’ll get makes clear the statement is false. It, and other links, defines the term as “a way of approaching decision making about clinical issues.”

A perfect example is the first item on the list above: evidence-based practice refers to specific treatment approaches which have been tested in research and found to be effective. Type the term into Google, and one of the FIRST hits you’ll get makes clear the statement is false. It, and other links, defines the term as “a way of approaching decision making about clinical issues.”

Said another way, evidence-based practice is a mindset — a way of approaching our work that has nothing to do with adopting particular treatment protocols.

Still, belief persists.

What can a reasonable person do to avoid falling prey to such falsehoods?

It’s difficult, to be sure. More, as busy as we are, and as much information as we are subjected to on a daily basis, the usual suggestions (e.g., read carefully, verify all facts independently, seek out counter evidence) will leave all but those with massive amounts of free time on their hands feeling overwhelmed.

And therein lies the clue — at least in part — for dealing with the “illusory truth effect.” Bottom line: if you try to assess each bit of information you encounter on a one-by-one basis, your chances of successfully sorting fact from fiction are low. Indeed, it will be like trying to quench your thirst by drinking from a fire hydrant.

To increase your chances of success, you must step back from the flood, asking instead, “what must I unquestioningly believe (or take for granted) in order to accept a particular assertion as true?” Then, once identified, ask yourself whether those assumptions are true?

Try it. Go back to the statements at the beginning of this post with this larger question in mind.

(Hint: they all share a common philosophical and theoretical basis that, once identified, makes verification of the specific statements much easier)

(Hint: they all share a common philosophical and theoretical basis that, once identified, makes verification of the specific statements much easier)

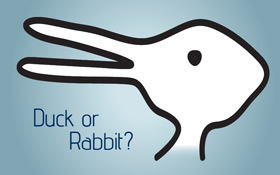

If you guessed the “medical model” (or something close), you are on the right track. All assume that helping relieve mental and emotional suffering is the same as fixing a broken arm or treating a bacterial infection — that is, to be successful a treatment containing the ingredients specifically remedial to the problem must be applied.

While mountains of research published over the last five decades document the effectiveness of the “talk therapies,” the same evidence conclusively shows “psychotherapy” does not work in the same way as medical treatments. Unlike medicine, no specific technique in any particular therapeutic approach has ever proven essential for success. None. Any claim based on a similar assumptive base should, therefore, be considered suspect.

Voila!

I’ve been applying the same strategy in the work my team and I have done on using measures and feedback — first, to show that therapists needed to do more than ask for feedback if they wanted to improve their effectiveness; and second, to challenge traditional notions about why, when, and with whom, the process does and doesn’t work. In these, and other instances, the result has been greater understanding and better outcomes.

So there you have it. Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

P.S: Registration for the Spring Feedback Informed Treatment intensives is now open. In prior years, these two events have sold out several months in advance. For more information or to register, click here or on the images below.

.jpg)