It’s a complaint I’ve heard from the earliest days of my career. Therapists do not read the research. I often mentioned it when teaching workshops around the globe.

“How do we know?” I would jokingly ask, and then quickly answer, “Research, of course!”

Like people living before the development of the printing press who were dependent on priests and “The Church” to read and interpret the Bible, I’ve long expressed concern about practitioners being dependent on researchers to tell them how to work.

- I advised reading the research, encouraging therapists who were skittish to skip the methodology and statistics and cut straight to the discussion section.

- I taught courses/workshops specifically aimed at helping therapists understand and digest research findings.

- I’ve published research on my own work despite not being employed by a university or receiving grant funding.

- I’ve been careful to read available studies and cite the appropriate research in my presentations and writing

I was naïve.

To begin, the “research-industrial complex” – to paraphrase American president Dwight D. Eisenhower – had tremendous power and influence despite often being unreflective of and disconnected from the realities of actual clinical practice. The dominance of CBT (and its many offshoots) in practice and policy, and reimbursement is a good example. In some parts of the world, government and other payers restrict training and reimbursement in any other modality – this despite no evidence CBT has led to improved results and, as documented previously on my blog, data documenting such restrictions lead to poorer outcomes.

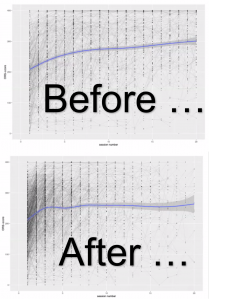

More to the point, since I first entered the field, research has become much harder to read and understand.

How do we know? Research!

Sociologist David Hayes wrote about this trend in Nature more than 30 years ago, arguing it constituted “a threat to an essential characteristic of the endeavor – its openness to outside examination and appraisal” (p. 746).

I’ve been on the receiving end of what Haye’s warned about long ago. Good scientists can disagree. Indeed, I welcome and have benefited from critical feedback provided when my work is peer-reviewed. At the same time, to be helpful, the person reviewing the work must know the relevant literature and methods employed. And yet, the ever-growing complexity of research severely limits the pool of “peers” able to understand and comment usefully, or – as I’ve also experienced – to those whose work directly competes with one’s own.

Still, as Hayes notes, the far greater threat is the lack of openness and transparency resulting from scientists’ inability to communicate their findings in a way that others can understand and independently appraise. Popular internet memes like, “I believe in science,” “stay in your lane,” and “if you disagree with a scientist, you are wrong,” are examples of the problem, not the solution. Beliefs are the province of religion, politics and policy. The challenge is to understand the strengths and limitations of the methodology and results of the process called science — especially given the growing inaccessibility of science, even to scientists.

Continuing with “business as usual” — approaching science as a “faith” versus evidence-based activity — is a vanity we can ill afford.

Until next time,

Scott

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence