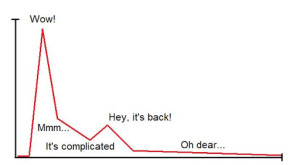

Last week, my inbox started filling with emails from colleagues about a new study. Working with a real world sample, researchers compared dynamic therapy to cognitive therapy and found…

(drum roll please)

NO DIFFERENCE IN OUTCOME!

Long ago, psychologist Saul Rosenzweig dubbed the equivalence in outcome between competing brands of psychotherapy, “The Dodo Verdict.”

(I’m the one on the right)

What’s surprising is all the attention the study has been getting. After all, the “Dodo verdict” is one of the most robust findings in the treatment literature. And yet, it remains a subject of controversy. For obvious reasons, those who advocate that certain therapies are more effective than others dislike the Dodo intensely. In fact, as I’ve reported several times on this blog, that group is forever claiming they’ve found the single study that proves it wrong.

Ultimately, however, the Dodo provides strong empirical support for something practitioners have long known: nothing works for everyone. To find the right path, therapists, and the people they serve, need choice.

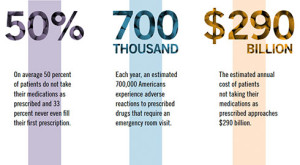

Personally, I believe a much more important, yet under reported, finding of the study is the number of people who dropped out after a single visit with their therapist. In this carefully controlled and executed study, 26% of people in both treatment conditions did not return for a second session. Slightly more than half—50%–attended 5 sessions or less. This after having endured a selection and recruitment process that retained only 5% of those initially screened for participation!

Beyond the impact on those seeking service (e.g., inadequate and ineffective care, longer waiting lists, etc.), unilateral client discontinuation and no shows, available evidence shows, “exact a significant financial burden in terms of staff salaries, overhead, and lost revenue, in addition to personnel losses resulting from low morale and high staff turnover.”

What can be done?

Three evidence-based ideas:

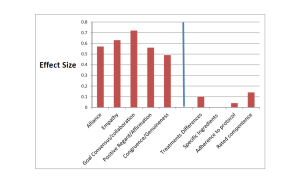

- Setting aside time at the outset of treatment specifically aimed at making people feel welcome and comfortable has consistently been shown to improve attendance. Known variously as “role preparation/indunction,” it’s similar to how you would treat a guest in your home, either formally or informally explaining the therapeutic process, addressing any concerns/apprehensions/misconceptions, and creating an expectation of success.

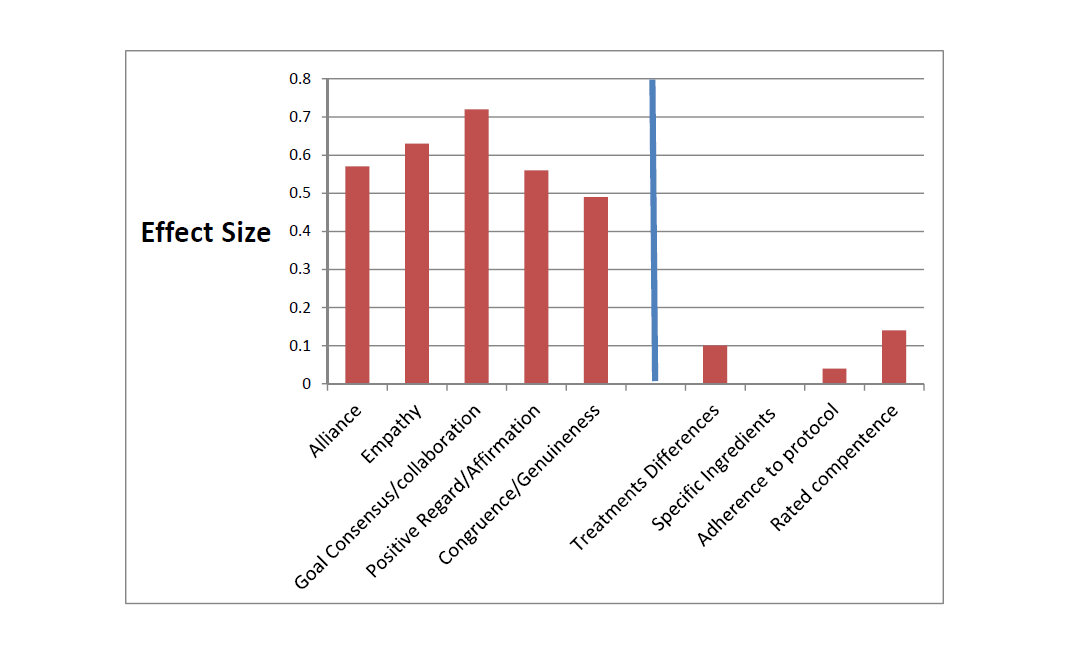

- Actively seek negative feedback about the therapeutic relationship. Clients rarely report negative reactions until they’ve already decided to quit (Horvath, 2001). Measuring and discussing the status of the working relationship has been shown to improve both retention and outcome.

- Monitor progress. Not surprisingly, a felt lack of improvement is predictive of service discontinuation. Clients whose therapists use measures to identify those not making progress or worsening stay longer and improve more than those who do not.

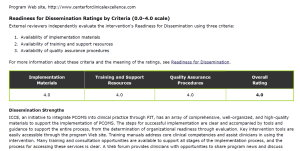

Learn more about how to create a culture of feedback and formally monitor the progress and the therapeutic relationship in this free article from the newly published book, Quality Improvement in Behavioral Health. Loads of “how to” resources on the ICCE YouTube channel as well. Check it out here.

with his story. Then, he played—doing with one hand what many would think impossible with two. When asked what drove him to continue in the face of so many challenges, he said, in a quiet yet confident voice, “Because there is so much to learn!”

with his story. Then, he played—doing with one hand what many would think impossible with two. When asked what drove him to continue in the face of so many challenges, he said, in a quiet yet confident voice, “Because there is so much to learn!”

liance and feedback literature, but also the first empirical model for how feedback can be used to resolve ruptures in the therapeutic relationship. What’s the secret? The entire study

liance and feedback literature, but also the first empirical model for how feedback can be used to resolve ruptures in the therapeutic relationship. What’s the secret? The entire study