In May 2012, I blogged about results from a Swedish study examining the impact of psychotherapy’s “favorite son”–cognitive behavioral therapy–on the outcome of people disabled by depression and anxiety. Like many other Western countries, the percentage of people in Sweden disabled by mental health problems was growing dramatically. Costs were skyrocketing. Even with treatment, far too many left the workforce permanently.

Sweden embraced “evidence-based practice”–most popularly construed as the application of specific treatments to specific disorders–as a potential solution. Socialstyrelsen, the country’s National Board of Health and Welfare, developed and disseminated a set of guidelines (“riktlinger”) specific to mental health practice. Topping the list? CBT.

A billion crowns were spent training clinicians in the method; another billion using it to treat people with diagnoses of depression and anxiety. As I reported at the time, the State’s “return on investment” was zilch. Said another way, the widespread adoption of method had no effect whatsoever on outcome (see Socionomen, Holmquist Interview). Not only that but many who were not disabled at the time they were treated with CBT became disabled along the way, bringing the total price tag, when combined with the 25% who dropped out of treatment, to a staggering 3.5 billon!

And now, a new study–this time from Norway, Sweden’s neighbor to the west.

Norwegian researchers looked at how the effectiveness of CBT has fared over time. Examining data from 70 randomized clinical trials, study authors Johnsen and Friborg found the approach to be roughly half as effective as it was four decades ago. Mind you, not 10 or 20 percent. Not 30 or 40. Fifty percent less effective! Cause for concern, to be sure.

So, what’s happening to CBT? Is the “favored son” losing its effectiveness?

Naturally, the results published by the Norwegian researchers generated a great deal of activity in social media. Critics were gleeful (see the comments at the end of the article). Proponents, of course, questioned the results.

If the findings are confirmed in subsequent studies, CBT will be in remarkably good company. Across a variety of disciplines–pharmacology, medicine, zoology, ecology, physics–promising findings often “lose their luster,” with many fading away completely over time (Lehrer, 2010; Yong, 2012). Alas, even in science, the truth occasionally wears off. In psychiatry and psychology, this phenomenon, known as the “decline effect,” is particularly vexing.

That said, while the study and commentary have managed to generate a modest amount of heat, they’ve shed precious little light on the question of how to improve the outcome of psychotherapy. After all, that’s what led Sweden to invest so heavily in CBT in the first place–doing so, it was believed, would improve the effectiveness of care. So today, I called Rolf Holmqvist.

Rolf is a professor in the Department of Behavioral Science and Learning at Linköping University. He’s also the author of the Swedish study I blogged about over three years ago. I wanted to catch up, find out what, if anything, had happened since he published his results.

“Some changes were made in the guidelines some time ago. In the case of depression, for example, the guidelines have become a little more open, a little broader. CBT is always on top, along with IPT, but psychodynamic therapy is now included…although it’s further down on the list.”

Sounded like progress, until Rolf continued, “They are broadening a bit. Still the fact is that if you look at the research, for example, with mild and moderate depression, almost any method works if it’s done systematically.”

Said another way, despite the lack of evidence for the differential effectiveness of psychotherapeutic approaches–in this case, CBT for depression–the mindset guiding the creation of lists of “specific treatments for specific disorders” remains.

Rolf’s sentiments are echoed by uber-researchers, Wampold and Imel (2015), who very recently pointed out, “Given the evidence that treatments are about equally effective, that treatments delivered in clinical settings are effective (and as effective as that provided in clinical trials), that the manner in which treatments are provided much more important than which treatment is provided, mandating particular treatments seems illogical. In addition, given the expense involved in “rolling out” evidence-based treatments in private practices, agencies, and in systems of care, it seems unwise to mandate any particular treatment.”

Right now, in Sweden, an authority within the Federal government (Riksrevisorn) is conducting an investigation evaluating the appropriateness of funds spent on training and delivery of CBT. In an article published yesterday in one of the countries largest newspapers , Rolf Holmqvist argues, “Billions spent–without any proven results.”

Returning to the original question: what can be done to improve the outcome of psychotherapy?

“We need transparent evaluation systems,” Rolf quickly answered, “that provide feedback at each session about the progress of treatment. This way, therapists can begin to look at individual treatment episodes, and be able to see when, where, and with whom they are and are not successful.”

“Is that on the agenda?” I asked, hopefully.

“Well,” he laughed, “here, we need to have realistic expectations. The idea of recommending that you should employ a clinician because they are effective and a good person, rather than because they can do a certain method, is hard for regulatory agencies like Socialstyrelsen. They think of clinicians as learning a method, and then applying that method, and that its the method that makes the process work…”

“Right,” I thought, “mindset.”

“…and that will take time,” Rolf said, “but I am hopeful.”

But, you don’t have to wait. You can begin tracking the quality and outcome of your work right now. It’s easy and free. Click here to access two simple scales–the ORS and SRS. the first measures progress; the second, the quality of the working relationship.

Next, read our latest article on how the field’s most effective practitioners use the measures to, as Rolf advised, “identify when, where, and with whom” they are and are not successful, and what steps they take to improve their effectiveness.

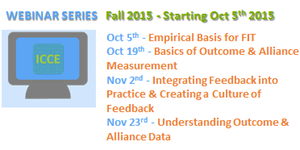

Finally, join colleagues from around the world for our Fall Webinar on “Feedback-Informed Treatment.”

We’ll be covering everything you need to know to integrate feedback into your clinical practice.

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

International Center for Clinical Excellence

Hi Scott-

The decline effect means to me that not only do we need to be able to replicate findings in order to have confidence in a research outcome, and not only do we need to carefully pick apart the methodology as best we can know it from the written report (which could leave out potentially powerful if subtly applied factors affecting the results), but in the case of strong positive results, even quite consistent ones, we need to let the phenomenon “age and mellow” before we should get all excited about how ‘real’ it is. That’s so difficult!

At the most recent Society for Psychotherapy Research conference in Philadelphia, Simon Goldberg and Zac Imel gave presentations on the same panel about a potentially huge pivot that insurance companies and health authorities might need to make to improve outcomes on a large scale. Taking advantage of the consistent finding of differential therapist effects (therapists seem more different in their outcomes than treatment approaches are), Goldberg showed that with the OQ-45, clients who stayed in therapy longer with the overall high-performing therapists had better outcomes the longer they stayed. Clients who stayed in therapy longer with the overall poorly-performing therapists had worse outcomes the longer they stayed (these clients still got better than they felt at intake, but the longer clients stayed the poorer their gains were from their intake scores). So rather than assuming that clients should just stay for a particular length of time “on average” these findings point to the possibility that health authorities should be determining who the better therapists are and then LEAVING THEM AND THEIR PATIENTS ALONE to do their work in whatever way they see fit, while working with the poorer performing therapists to help them improve, and/or limiting their treatment lengths until they are doing better with patients.

Meanwhile, Imel described his Monte Carlo simulation study in which removing the very poorest-performing therapists over 10 years from a large sample of typical therapists with a typical range of outcomes would (naturally) improve the overall quality of service (outcomes) to patients by dramatically increasing the number of patients expected to report real clinical change. While this makes sense intuitively, it served as a visual and numeric model for how many thousands of clients would have gotten better outcomes if this had been done.

Now, if these changes were made based on Goldberg’s and Imel’s studies, would we see this ‘therapist effect’ also decline over the years? Would patients’ gains not show so much luster in 20 or 30 years? Will the way we measure outcomes evolve in such a way that these gains shrink or change over time? All of this calls for modesty in our claims, and great care in the firmness of our assumptions and the creation of new, broad, and expensive policies–whether about CBT or any other method for improving outcomes.

Cheers,

Jason

Hey Scott, what do you think about the possibility that it lost effectiveness not because the approach is less potent, but because they retrained clinicians from other approaches into CBT, and dragged the mean down with it. Seems that you would have people much less experienced in that approach having to deliver it, and at the same time took those providers away from the approaches they may have already been doing competently. Historically you could probably argue that as new treatments emerge, the most attuned providers will be in board. Once they reach a ubiquitous level, everyone starts using them (aka less attuned, possibly less competent providers) and the mean effectiveness drops. Thoughts?

Very interesting thoughts. Bill Miller, of motivational interviewing fame, essentially found that same result. People doing MI weren’t as effective as him doing it!

To what extent, if at all, was the observed decline in the effectiveness of CBT associated with its designation by institutions (insurance, clinical institutions, . . .) as the preferred or required modality?

Might it be that before that designation and requirement those who practiced CBT were doing so because they had chosen it themselves as match for their approach and perceptions of client needs? To put this in the Inst. for Clinical Excellence terms, their choice of CBT was itself in a way “feedback-informed,” in the sense that the clinician’s observations (and perhaps their direct requests for feedback if they were doing that) had shown them its usefulness. Thus they were using CBT because of their observations of its usefulness.

In contrast, when using CBT because of outside mandate, many clinicians would be using it for that reason alone. Those would not have been convinced of its usefulness by their own observations of clients, and their use of CBT would not be dependent on such observations.

So we might have two co-factors acting in this observed decline, both of them the effects of the mandate: Unconvinced clinicians, and use of CBT not dependent on continuing clinician observations of the indirect feedback provided by client progress.

I have no surveys or studies on this subject. My own anecdotal experience with untrained checking in with clients – in a spirit of openness and readiness, even eagerness — to receive their responses and discuss them and jointly devise changes seems helpful to them and to me. The way I understand this benefit of feedback is that it provides the client an experience of empowerment in a situation of support, something quite the opposite of what traumatic incidents or chronic abuse or poor attachment history has equipped them with.

Joseph Maizlish, M.A., M.F.T.

Los Angeles, CA

In my opinion each psychotherapist uses a method he/she likes and his/her enthusiasm makes the method more effective. Similarly, a patient usually prefers a certain method to others. From this point of view imposing one single method on the whole nation was not very wise to begin with.