Just over a year ago, I blogged about an article that appeared in one of the U.K.’s largest daily newspapers, The Guardian. Below a picture of an attractive, yet dejected looking woman (reclined on a couch), the caption read, “Major new study reveals incorrect…care can do more harm than good.”

I was interested.

As I often do in such cases, I wrote directly to the researcher cited in the article asking for a reprint or pre-publication copy of the study. No reply. One month later, I wrote again. Still, no reply. Two months after my original email, I received a brief note thanking me for my interest in the study and offering to share any results once they became available.

“Wait a minute,” I immediately thought, “The results of this ‘major new study’ about the harmful effects of psychotherapy had already been announced in a leading newspaper. How could they not be available?” Then I wondered, “If there are no actual results to share, what exactly was the article in The Guardian based on?”

So-called “adverse events” are a hot topic at the moment. That some people deteriorate while in care is not in question. Research dating back several decades puts the figure at about 10%, on average (Lambert, 2010). When those being treated are adolescents or children, the rates are twice as high (Warren et al., 2009).

Putting this in context, compared to medical procedures with effect sizes similar to psychotherapy (e.g., coronary artery bypass surgery, stages II and III breast cancer, stroke), the rate is remarkably low. Nonetheless, it is a matter of concern–especially given research showing that therapists are not particularly adept at recognizing when those they serve deteriorate in their care (Hannan et al., 2005)

The question, of course, is the cause?

To date, whenever the question of adverse events is raised, two “usual suspects” are trotted out: (1) the method of treatment used; and (2) the therapist. Let’s take a closer look at each.

In an October 2914 article published in World Psychiatry, Linden and Schermuly-Haupt wrote about estimates of side effects associated with specific methods of treatment that had been reported in an earlier study by Swiss researchers. The numbers were shocking. Patient reported “burdens caused by therapy” were 19.7% with CBT, 20.4% for systemically oriented treatments, 64.8% with humanistic approaches, and a staggering 94.1% with psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Based on such results, one could only conclude that anyone seeking anything other than CBT should have their head examined.

There is only one problem. The figures reported were wrong. Completely and utterly wrong. Linden and Schermuly-Haupt made an arithmetic error and, as a result, totally misinterpreted the Swiss findings. Read the study for yourself. When it comes to adverse events in psychotherapy, CBT–the fair-haired child of the evidence-based practice movement–is not better. Indeed, as the study clearly shows, people treated with humanistic and systemic approaches suffered fewer “burdens” than expected, while those in CBT had a slightly higher, although not statistically significant, level. More, the observed percentage of people in care who perceived the quality of the therapeutic relationship–the single most potent predictor of engagement and outcome–as poor was significantly higher than expected in CBT and lower for both humanistic and systemic approaches.

How could the researchers have gotten it so wrong?

As I pointed out in my blog over year ago, despite claims to the contrary (e.g., Lilenfeld, 2007), no psychotherapy approach tested in a clinical trial has ever been shown to reliably lead to or increase the chances of deterioration. NONE. Scary stories about dangerous psychological treatments are limited to a handful of fringe therapies–approaches that have been never vetted scientifically and which all practitioners, but a few, avoid. In short, its not about the method.

(By the way, over a month ago, I wrote to the lead author of the paper that appeared in World Psychiatry via the ResearchGate portal–a site where scholars meet and share their publications–providing a detailed breakdown of the statistical errors in the publication. No response thusfar)

With only one suspect left, attention naturally turns to the therapist–you know, the “bad apple” in the bunch. Here’s what we know. That some practitioners do more harm than others is not exactly news. Have you seen the new biopic Love & Mercy, about the life of Beach Boy Brian Wilson? You should. The acting is superb.

Wilson’s therapist, psychologist Eugene Landy (chillingly recreated by actor Paul Giamatti), is a prime example of an adverse event. See the film and you’ll most certainly wonder how the guy kept his license to practice so long. And yet, as I also pointed out in my blog last year, there are too few such practitioners to account for the total number of clients who worsen. Consider this unsettling fact: beyond the 10% of those who deteriorate in psychotherapy, an additional 30 and 50% experience no benefit whatsoever!

Where does this leave us when it comes to adverse events in psychotherapy?

Whatever the cause, lack of progress and risk of deterioration are issues for all clinicians and clients. The key to addressing these problems is tracking progress from visit to visit so that those not improving, or getting worse, can be identified and offered alternatives. It’s that simple.

Right now, practitioners can access two simple, easy-to-use scales for free at: www.whatispcoms.com. Both have been tested in multiple, randomized, clinical trials and deemed evidence-based by the Federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

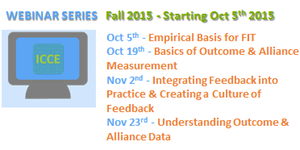

Learning to use the tools isn’t difficult. It costs nothing to join the International Center for Clinical Excellence and begin interacting with professionals around the world who are using the measures to improve the quality and outcome of behavioral health services. More detailed instruction is available at the upcoming webinar:

Join us in tackling the issue of adverse events in psychotherapy. In the meantime, be sure and leave a comment below.

Best wishes for the summer,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

P .S.: On the one year anniversary of my original email to the reseacher cited in the Guardian, I sent another. That’s over a month ago. So far, no reply. By contrast, the reporter who broke the story, Sarah Boseley , wrote back within a half hour! She’s following up her sources. I’ll let you know if she gets a response.

Thank you Scott for your integrity, elegance and clarity.

And are these researchers guilty of sins of omission or commisison?

Michael. No sure which researchers you are referring to in the piece. But, as Paul Simon sings, “A man sees what he wants to see, and disregards the rest.”

Hi Scott,

I greatly appreciate your persistent, clear and critical attention to these kinds of muddles! You’ve highlighted another prime example of humans not letting the facts (and critical thinking) get in the way of telling a compelling story. As the light keeps getting brighter, the fair-haired child may be required to sit down and let the common speak?

I don’t think the “fair-haired” child will ever sit down…willingly…OTHERS need to stand up…Talk loudly with data!

Regrettably, you tease my appetite, but you are not serving the expected side-dish here: “a detailed breakdown of the statistical errors in the publication”.

How can I get access to what you are referring to?

Not that I doubt your conclusions, but we all have a lot to learn from errors – others’ and our own.

Tormod…I’ve provided ALL the links to the articles on which the information is based. Just click and review.

Great write up of a very interesting topic. I’m a bit surprised at the Guardian doing some apparently messy work on a topic they would consider to be pretty core to their editorial interests.

Good post I think I’m going to link to this post for some of my customers as many seem to have no clue what so ever about spam

Psychotherapy Shepherds Bush