Nearly three years have passed since I blogged about claims being made about the impact of routine outcome monitoring (ROM) on the quality and outcome of mental health services. While a small number of studies showed promise, others results indicated that therapists did not learn from nor become more effective over time as a result of being exposed to ongoing feedback. Such findings suggested that the focus on measures and monitoring might be misguided–or at least a “dead end.”

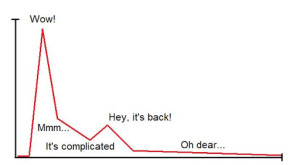

Well, the verdict is in: feedback is not enough to improve outcomes. Indeed, researchers are finding it hard to replicate the medium to large effects sizes enthusiastically reported in early studies, a well-known phenomenon called the “decline effect,” observed across a wide range of scientific disciplines.

In a naturalistic multisite randomized clinical trial (RCT) in Norway, for example, Amble, Gude, Stubdal, Andersen, and Wampold (2014) found the main effect of feedback to be much smaller (d = 0.32), than the meta-analytic estimate reported by Lambert and Shimokawa (2011 [d = 0.69]). A more recent study (Rise, Eriksen, Grimstad, and Steinsbeck, 2015) found that routine use of the ORS and SRS had no impact on either patient activation or mental health symptoms among people treated in an outpatient setting. Importantly, the clinicians in the study were trained by someone with an allegiance to the use of the scales as routine outcome measures.

Fortunately, a large and growing body of literature points in a more productive direction. Consider the recent study by De Jong, van Sluis, Nugter, Heiser, and Spinhoven (2012), which found that a variety of therapist factors moderated the effect ROM had on outcome. Said another way, in order to realize the potential of feedback for improving the quality and outcome of psychotherapy, emphasis must shift away from measurement and monitoring and toward the development of more effective therapists.

What’s the best way to enhance the effectiveness of therapists? Studies on expertise and expert performance document a single, underlying trait shared by top performers across a variety of endeavors: deep domain-specific knowledge. In short, the best know more, see more and, accordingly, are able to do more. The same research identifies a universal set of processes that both account for how domain-specific knowledge is acquired and furnish step-by-step directions anyone can follow to improve their performance within a particular discipline. Miller, Hubble, Chow, & Seidel (2013) identified and provided detailed descriptions of three essential activities giving rise to superior performance. These include: (1) determining a baseline level of effectiveness; (2) obtaining systematic, ongoing feedback; and (3) engaging in deliberate practice.

I discussed these three steps and more, in a recent interview for the IMAGO Relationships Think Tank. Although intended for their members, the organizers graciously agreed to allow me to make the interview available here on my blog. Be sure and leave a comment after you’ve had a chance to listen!

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

www.whatispcoms.com

www.iccexcellence.com

Scott, have you ever found clients to be resistant to filling out the ORS and SRS at every single session? If so, what do you recommend to overcome that resistance?

I am confused. Isn’t this what FIT was all about? Are you changing your mind?

Hi Allyson, I think what Scott is impressing upon us is that what has been learned about Feedback Informed Therapy is that anything that is applied in a mechanical, manualized or routine way does not by itself improve outcomes. It is when all three components are applied as Scott wrote: “Miller, Hubble, Chow, & Seidel (2013) identified and provided detailed descriptions of three essential activities giving rise to superior performance. These include: (1) determining a baseline level of effectiveness; (2) obtaining systematic, ongoing feedback; and (3) engaging in deliberate practice.” Without the feedback component, we would not be alerted to any areas for improving outcome with this particular client or as a therapist in general, nor would we be able to identify areas for our own improvement. He is pointing out that research on exceptional performance is adding the deliberate practice component here, that feedback by itself offers little promise, but doing something intentional with that feedback is the very spirit of FIT. That is my understanding anyway, for what its worth. Hope that makes sense.

EXACTLY George! Thanks so much for your comment. Also, I’m working hard to counter the sole emphasis on measurement.

Thanks for the clarification! 🙂

This is an exciting discussion. In my view there is some confusion as to why and how systematic documentation/ measurement of feedback should take place; probably the mechanisms behind the benefit to outcomes are still somewhat in the dark in many cases.

Studies that rely on designs where the control group provides feedback using the same scales as the intervention group seem to reveal, that the mere measurement of feedback is not in itself assumed to contribute to positive outcomes. The active component that is meant to make the difference between the intervention and the control group is the reception of the feedback by the therapist.

Of course, having the feedback is a necessary but insufficient condition for actually engaging in understanding and responding adequately to client feedback. So along these lines, it is equally important for an evaluation to study how therapists actually use (respond to) client feedback – during sessions with their clients, and during team consultations.

All of this has significant consequences for how the benefit of FIT can be obtained and evaluated; and for the reach of the conclusions of many of the studies conducted.

I am also confused. Here, you seem to say feedback (e.g. ORS & SRS) is not significantly effective, yet in the interview with IMAGO you seem to say it is. Are you saying that feedback ALONE is not sufficient? If so, when have you suggested otherwise?? Would the take away then be: Continue to use systematic feedback tools, but know that these are not enough to make you a better therapist.

Thanks!

Hi Scott,

I’m a little confused!

While I was not able to access the entire article by de Jong K1, van Sluis P, Nugter MA, Heiser WJ, Spinhoven P., I was able to read the abstract.

They seem to be concluding that feedback is not effective under all circumstances, and that therapist factors are important for not-on-track cases. Furthermore, when feedback was effective it appeared to be related to therapist factors such as, “internal feedback propensity, self-efficacy, and commitment to use the feedback.”

If you can, please explain what “internal feedback propensity” and “self-efficacy” mean. The reason I ask is that I would like to know how they are similar to (or different from) the factors you (and others) assert to be the three components critical for superior performance:

(1) determining a baseline level of effectiveness;

(2) obtaining systematic, ongoing, formal feedback; and

(3) engaging in deliberate practice.

It seems to me that “internal feedback propensity” (and even the drive for self-efficacy) may be more of a natural character trait or – for want of a better word – talent. If so, would that be contrary to your belief that “A fundamental finding of the research on superior performance is that talent is not a function of genetics…”?

Furthermore, where does the tendency to engage in deliberate practice come from?

I guess I’m not yet convinced that “top performers” do not come into the world with certain “gifts”.

Best!

Patrick

Hi Patrick:

Thanks for taking the time to reply. Our field has been in search of a method that improves outcomes for decades. Every inventor that comes along claims as much. Ultimately, and in each instance, the effectiveness of the tools are shown to vary depending on WHO uses them. Measurement is no different. Their helpfulness depends on the user. At present, researchers are working hard to understand what makes for an effective therapist. As George notes below, I’ve long maintained that administering measures is NOT enough. Still, hyperbolic claims continue, with some claiming they are the most important development in the history of the field since the very invention of therapy.

For my part, I am really excited about what we are learning. Finally out from under the search for specific methods for specific diagnoses, an entire new focus is being brought to the work. Chow’s brand new study shows that top performers spend more time engaged in deliberate practice. We are currently, along with a number of other researchers, exploring how to incorporate such findings into training of clinicians. For example, we know that more effective clinicians, form better alliances, so we have a research study going training therapists to respond empathically to difficult situations. Other researchers are looking at other variables, such as “internal feedback propensity,” or the willingness to seek and use feedback. While using different terms, the Chow study, along with others, identified similar findings. For example, more effective therapists evince more surprise in response to feedback, the precursor to learning. Said another way, if you are not surprised by feedback, you either: (1) didn’t hear it; or (2) did hear it, but did not consider it newsworthy. Anyway, stay tuned. And hey, join us in August 2016, for our professional development intensive. There, we lay out all of the current findings as well as help participants apply them to their practice: http://www.eventbrite.ie/e/fit-professional-development-intensive-2016-tickets-17740785166

The finding reflects my experience that just collecting data/obtaining feedback is not enough – it’s what the practitioner does with the information and the extent to which the practitioner engages in ‘deliberate practice’ – i.e. ‘Feedback…… informed.. practice’ and how the learning is applied.

Exactly Wendy. And this is why I’ve been warning about claims made by some advocates for nearly three years. The real risk is that research aimed at investigating what really matters will end once the headline grabbing claims about measurement are proven hyperbolic.