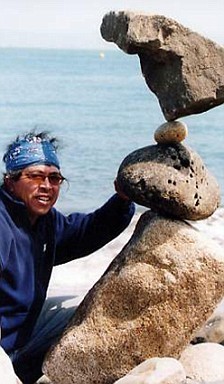

Trip-Advisor scores it # 11 out of 45 things to do Sausalito, California. No, it not’s the iconic Golden Gate Bridge or Point Bonita Lighthouse. Neither is it one of the fantastic local restaurants or bars. What’s more, in what can be a fairly pricey area, this attraction won’t cost you a penny. It’s the gravity-defying rock sculptures of local performance artist, Bill Dan.

So impossible his work seems, most initially assume there’s a trick: magnets, hooks, cement, or pre-worked or prefab construction materials.

Watch for a while, get up close, and you’ll see there are no tricks or shortcuts. Rather, Bill Dan has vision, a deep understanding of the materials he works with, and perseverance. Three qualities that, it turns out, are essential in any implementation.

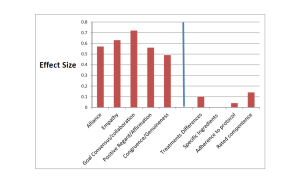

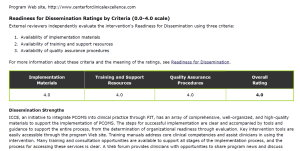

Over the last decade, I’ve had the pleasure of working with agencies and healthcare systems around the world as they work to implement Feedback-Informed Treatment (FIT). Not long ago, FIT–that is, formally using measures of progress and the therapeutic alliance to guide care–was deemed an evidence-based practice by SAMHSA, and listed on the official NREPP website. Research to date shows that FIT makes the impossible, possible, improving the effectiveness of behavioral health services, while simultaneously decreasing costs, deterioration and dropout rates.

Over the last decade, a number of treatment settings and healthcare systems have beaten the odds. Together with insights gleaned from the field of Implementation Science, they are helping us understand what it takes to be successful.

One such group is Prairie Ridge, an integrated behavioral healthcare agency located in Mason City, Iowa. Recently, I had the privilege of speaking with the clinical leadership and management team at this cutting-edge agency.

Click on the video below to listen in as they share the steps for successfully implementing FIT that have led to improved outcomes and satisfaction across an array of treatment programs, including residential, outpatient, mental health, and addictions.

Until next time,

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

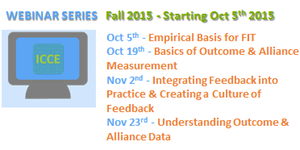

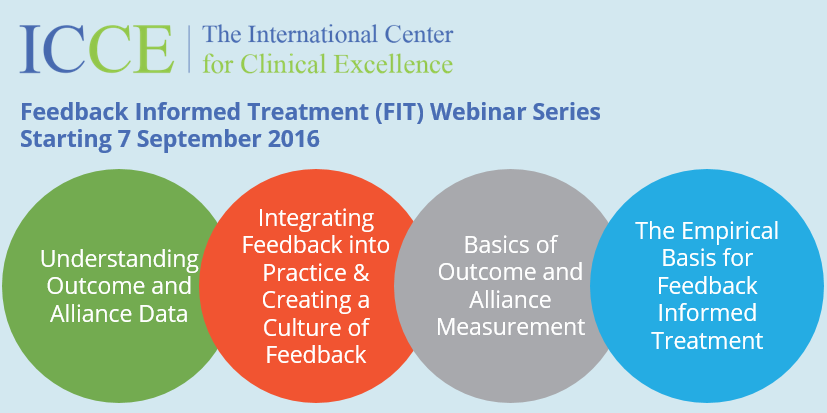

P.S.: Looking for a way to learn the principles and practice of Feedback Informed Treatment? No need to leave home. You can learn and earn CE’s at the ICCE Fall FIT Webinar. Register today at: https://www.eventbrite.ie/e/fall-2016-feedback-informed-treatment-webinar-series-tickets-26431099129.

between psychologist Eugene Landy and his famous client, Beach Boy Brian Wilson. In a word, it was disturbing. The psychologist did “24-hour-a-day” therapy, as he termed it, living full time with the singer-songwriter, keeping Wilson isolated from family and friends, and on a steady dose of psychotropic drugs while simultaneously taking ownership of Wilson’s songs, and charging $430,000 in fees annually. Eventually, the State of California intervened, forcing the psychologist to surrender his license to practice. As egregious as the behavior of this practitioner was, the problem of deterioration in psychotherapy goes beyond the field’s “bad apples.”

between psychologist Eugene Landy and his famous client, Beach Boy Brian Wilson. In a word, it was disturbing. The psychologist did “24-hour-a-day” therapy, as he termed it, living full time with the singer-songwriter, keeping Wilson isolated from family and friends, and on a steady dose of psychotropic drugs while simultaneously taking ownership of Wilson’s songs, and charging $430,000 in fees annually. Eventually, the State of California intervened, forcing the psychologist to surrender his license to practice. As egregious as the behavior of this practitioner was, the problem of deterioration in psychotherapy goes beyond the field’s “bad apples.”

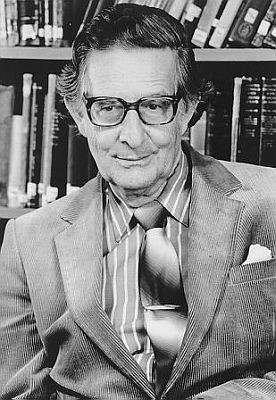

Norwegian psychologist Jørgen A. Flor just completed a study on the subject. We’ve been corresponding for a number of year as he worked on the project. Given the limited information available, I was interested.

Norwegian psychologist Jørgen A. Flor just completed a study on the subject. We’ve been corresponding for a number of year as he worked on the project. Given the limited information available, I was interested.

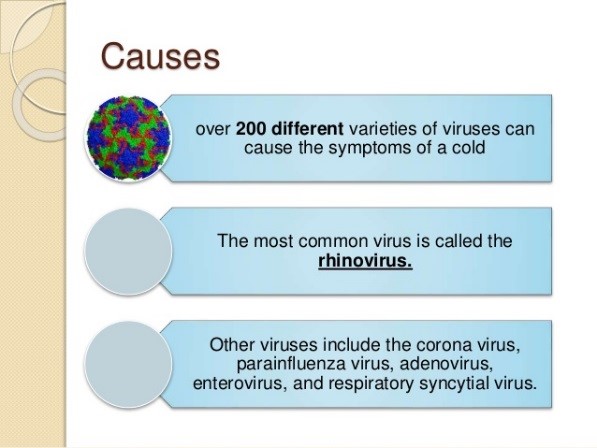

ment still popular today; namely, that by including studies of varying (read: poor) quality, Smith and Glass OVERESTIMATED the effectiveness of psychotherapy. Were such studies excluded, they contended, the results would most certainly be different and behavior therapy—Eysenck’s preferred method—would once again prove superior.

ment still popular today; namely, that by including studies of varying (read: poor) quality, Smith and Glass OVERESTIMATED the effectiveness of psychotherapy. Were such studies excluded, they contended, the results would most certainly be different and behavior therapy—Eysenck’s preferred method—would once again prove superior.

with his story. Then, he played—doing with one hand what many would think impossible with two. When asked what drove him to continue in the face of so many challenges, he said, in a quiet yet confident voice, “Because there is so much to learn!”

with his story. Then, he played—doing with one hand what many would think impossible with two. When asked what drove him to continue in the face of so many challenges, he said, in a quiet yet confident voice, “Because there is so much to learn!”

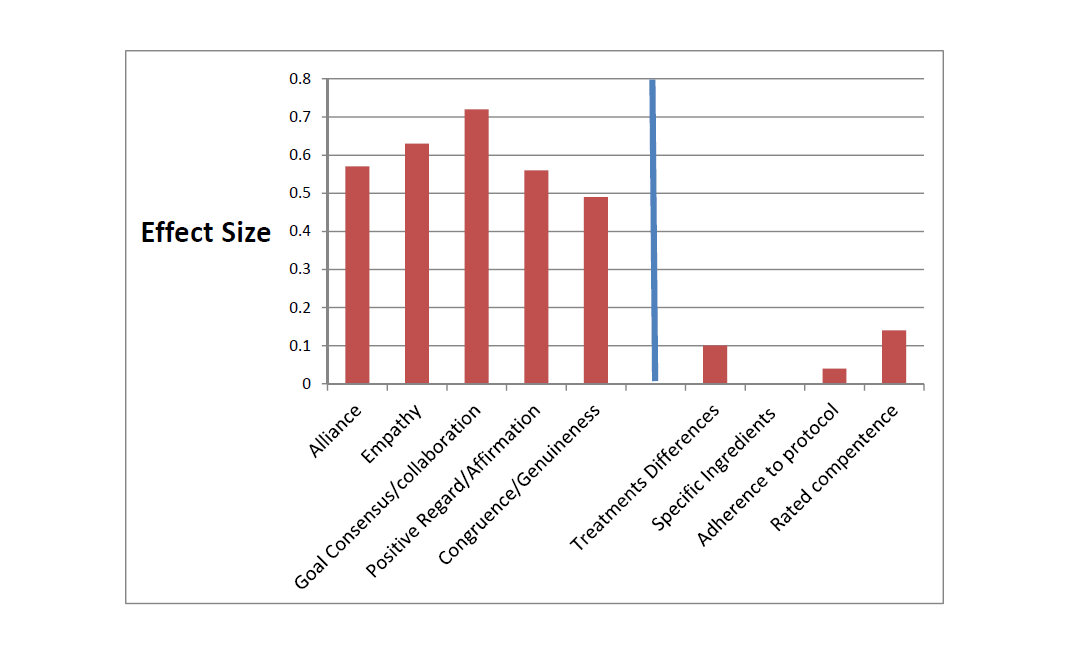

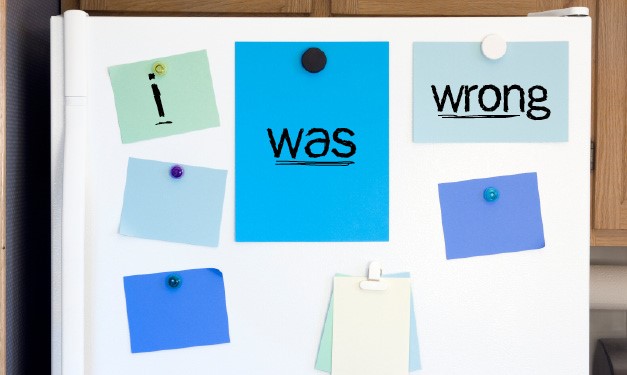

ng a mistake presumes knowing one has been made. It’s easier said than done. Clinicians’

ng a mistake presumes knowing one has been made. It’s easier said than done. Clinicians’ liance and feedback

liance and feedback

ave not.

ave not.

ing Psychology.

ing Psychology.

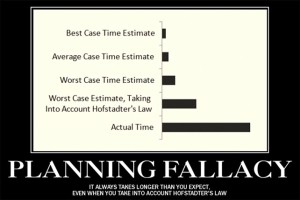

e boundary between “belief in the process” and “denial of reality” is remarkably fuzzy. Hope is a significant contributor to outcome—accounting for as much as 30% of the variance in results. At the same time, it becomes toxic when actual outcomes are distorted in a manner that causes practitioners to miss important opportunities to grow and develop—not to mention help more clients.

e boundary between “belief in the process” and “denial of reality” is remarkably fuzzy. Hope is a significant contributor to outcome—accounting for as much as 30% of the variance in results. At the same time, it becomes toxic when actual outcomes are distorted in a manner that causes practitioners to miss important opportunities to grow and develop—not to mention help more clients.

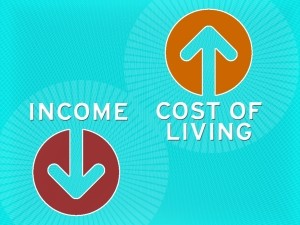

les and regulation are on the increase. Incomes are on the decline. They know the value of the work they do. They can see it in the people they treat. Instead of recognizing the value of the services offered, the effectiveness of the field, it’s methods, and practitioners are called into question.

les and regulation are on the increase. Incomes are on the decline. They know the value of the work they do. They can see it in the people they treat. Instead of recognizing the value of the services offered, the effectiveness of the field, it’s methods, and practitioners are called into question.