Search Results for: implementation

From Evidence-based Practice to Cultural Change: Steps to Successful Implementation

Chances are your are carrying a smartphone–maybe you’re even reading this post on your Android or Iphone! One thing I’m almost certain of is that the device you own–can’t live without–is not a Nokia.

Chances are your are carrying a smartphone–maybe you’re even reading this post on your Android or Iphone! One thing I’m almost certain of is that the device you own–can’t live without–is not a Nokia.

The nearly complete absence of the brand is strange. Not long ago, the company dominated the mobile phone market. At one time, seventy percent of phones in consumers’ hands were made by Nokia.

“And then,” to quote Agathe Christie, “there were none!”

Today, Nokia’s global market share is an anemic 3 %.

What happened? Here, the answer is no mystery. It was not a lack of position, talent, innovative ideas, or know-how. Rather, the company failed at implementation. Instead of rapidly adapting to changing conditions, it banked on its brand name and past success to carry it through. Vague considerations trumped concrete goals. Spreadsheets and speeches replaced communication, consensus-building, and commitment. The moral of the story? No matter how successful the brand or popular the product, implementation is hard.

Nowhere is this truer than in healthcare. Change is not only constant but accelerating. Each week, hundreds of research findings are published. Just as frequently, new technologies come online. All have the potential to do good, to improve the quality and outcome of treatment.

Research to date, for example, documents that seeking ongoing, formal feedback from those receiving behavioral health services as much as triples the effectiveness of the care offered, while simultaneously cutting the rate of drop out by 50%, and decreasing the risk of deterioration by 33%. Enough evidence has amassed to warrant the approach–known as, “Feedback Informed Treatment”– being listed on the National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices.

Any yet, despite the massive amount of time and resources, agencies and practitioners devote to staying “up-to-date,” most implementation efforts struggle, and far too many fail–according to the available evidence, about 70-95% (a figure equivalent to the number of start-up businesses in the United States that belly up annually).

In their chapter in the new book, Feedback Informed Treatment in Clinical Practice, Randy Moss and Vanessa Mousavizadeh, provide step-by-step instructions, based on the latest research and real-world experience, for creating an organizational culture that supports implementation success. Recently, I had a chance to talk with Randy about the chpater. Whether you’ve got the book or not, I think you’ll find the knowledge and experience in the video below, helpful:

Online version of the Fidelity Readiness Index and Fidelity Measure

In the meantime, while on the subject of implementation, here’s a cool, electronic version of a tool you can use to track the progress of your efforts. It helps identify where you and your organization are in the process as well as identify and set goals in order to remain on track (it’s one of the reasons reviewers at SAMHSA gave our application perfect marks for implementation support). Thanks to my Danish colleague, Rasmus Kern for developing and making it available. By the way, the program contains both English and Danish versions (we’ll be releasing more languages soon).

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Implementation Science, FIT, and the Training of Trainers

The International Center for Clinical Excellence (ICCE) is pleased to announce the 6th annual Training of Trainers event to be held in Chicago, Illinois August 6th-10th, 2012. As always, the ICCE TOT prepares participants provide training, consultation, and supervision to therapists, agencies, and healthcare systems in Feedback-Informed Treatment (FIT). Attendees leave the intensive, hands-on training with detailed knowledge and skills for:

- Training clinicians in the Core Competencies of Feedback Informed Treatment (FIT/CDOI);

- Using FIT in supervision;

- Methods and practices for implementing FIT in agencies, group practices, and healthcare settings;.

- Conducting top training sessions, learning and mastery exercises, and transformational presentations.

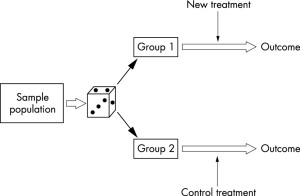

Multiple randomized clinical trials document that implementing FIT leads to improved outcomes and retention rates while simultanesouly decreasing the cost of services.

This year’s “state of the art” faculty include: ICCE Director, Scott D. Miller, Ph.D., ICCE Training Director, Julie Tilsen, Ph.D., and special guest lecturer and ICCE Coordinator of Professional Development, Cynthia Maeschalck, M.A.

Join colleagues from around the world who are working to improve the quality and outcome of behavioral healthcare via the use of ongoing feedback. Space is limited. Click here to register online today. Last year, one participants said the training was, “truly masterful. Seeing the connection between everything that has been orchestrated leaves me amazed at the thought, preparation, and talent that has cone into this training.” Here’s what others had to say:

Join colleagues from around the world who are working to improve the quality and outcome of behavioral healthcare via the use of ongoing feedback. Space is limited. Click here to register online today. Last year, one participants said the training was, “truly masterful. Seeing the connection between everything that has been orchestrated leaves me amazed at the thought, preparation, and talent that has cone into this training.” Here’s what others had to say:

Simple, not Easy: Using the ORS and SRS Effectively

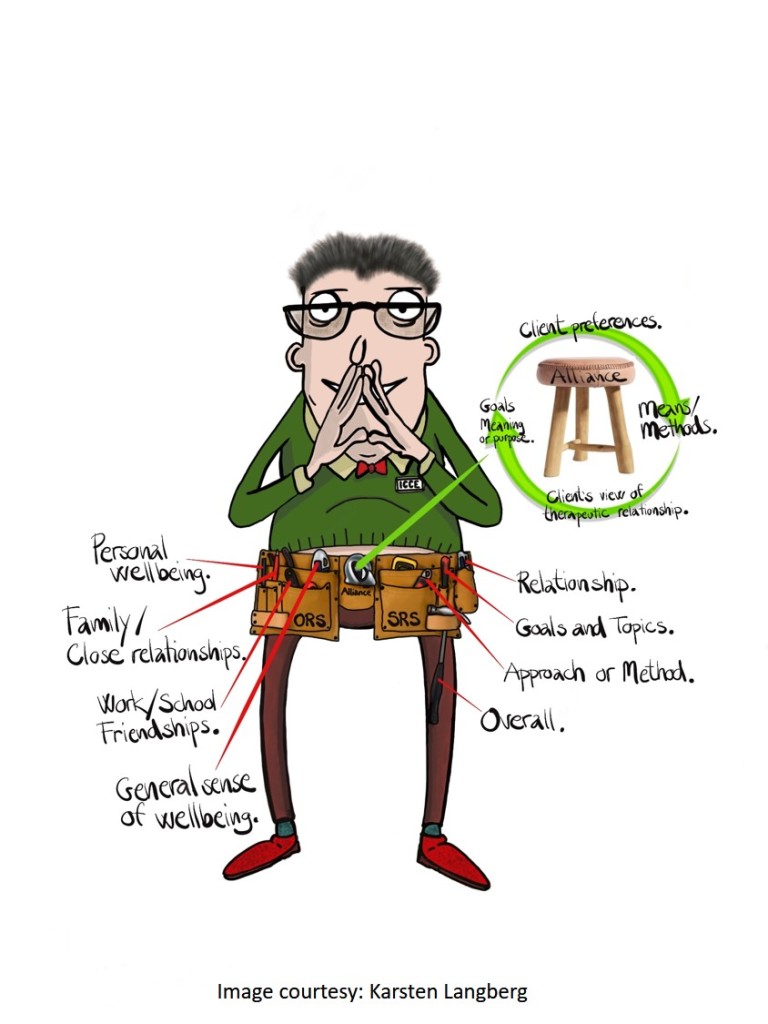

How difficult could it be? One scale to assess progress, a second to solicit the client’s perception of the therapeutic relationship. Each containing four questions, administration typically takes between 30 to 60 seconds.

Since first being developed 23 years ago, scores of randomized-controlled and naturalistic studies have found the use of simple tools in care significantly improves outcome (1, 2).

And yet, while both simple and effective, research shows integrating the measures into care is far from easy. First came studies documenting that implementing feedback-informed care took time — up to three years for agencies to see results (3). It’s why we developed and have been offering a two-day itensive training on the subject for more than a decade — the only one of its kind. The next one is scheduled for January (click here for more information or to register). We outline the evidence-based steps and help managers, supervisors, team leads and staff develop a plan.

Other studies show while the vast majority of clients have highly favorable reactions to the use of the scales in care, they do have questions. In a recently survey of 13 clients in a private practice setting, Glenn Stone and colleagues (4) reported 70% were surprised at being asked for feedback! More than half found it helpful to see their progress represented graphically from week to week, roughly the same number who felt the scales helped them identify and maintain the right focus in sessions. At the same time, a handful reported feeling confused about the some of the questions; specifically, how to answer an item (e.g., social well being) when it contained multiple descriptors (e.g., school, work and friendship) — each of which could be answered differently.

Such a fantastic question! One we have addressed, among many others, at every three-day, Feedback Informed Treatment Intensive since 2003 (the next one scheduled back-to-back with the Implementation training in January). Seeing the question in this research report made me think I needed to do a “FIT tip” video for those who’ve started using the measures but have yet to attend.

So what is the “best practice” when clients ask how to complete a question which contains multiple descriptors?

Incentivising the use of FIT

The evidence shows that using standardized measures to solicit feedback from clients regarding progress and their experience of the working relationship improves retention and outcome.

How much? By 25% (1)

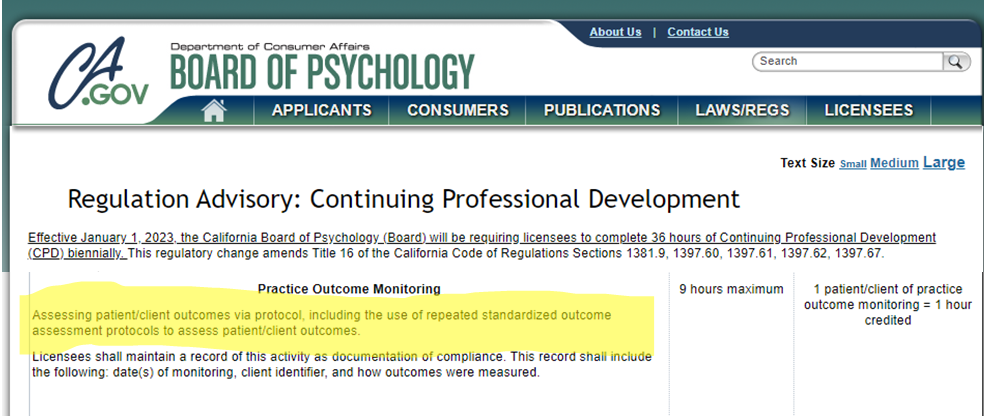

And now, major news out of California.

Psychologists — who are required to earn 36 hours of continuing education credits every other year — can now earn credit towards renewal of their license by implementing feedback-informed treatment (FIT) in their daily clinical work (2)!

Here’s the challenge. The same body of research documenting that FIT works, shows clinicians struggle when it comes to putting it into practice. Private practitioners express concerns about the time it takes. Those working in agencies talk about the challenges of finding alternatives when FIT data indicate the present course of treatment is not working. Finally, many who start, stop after a short while, noting that FIT didn’t add much beyond their “clinical knowledge and experience.”

All such concerns are real. Indeed, as reported a few years back on this blog (3), implemention takes time and skill — in agency settings, up to three years of effort, support and training before the benefits of being feedback-informed begin to materialize. When they do, however, clients are 2.5 times more likely to benefit from care.

So, don’t give-up. Instead, upskill!

In September, the International Center for Clinical Excellence is sponsoring the FIT “Training of Trainers.” Held only once every-other-year, the TOT focuses exclusively on the process of training and supporting others in their use of feedback informed treatment. As with all ICCE events, space is limited to 40 participants. Click on the link above or icon below for more information or to register!

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, ICCE

Does FIT work with all clients?

It’s a question that comes up at some point in most trainings on feedback-informed treatment (FIT):

“Can I use FIT with all my clients?”

Having encountered it many times, I now have a pretty good sense of the asker’s concerns. Given our training as mental health professionals, we think in terms of diagnosis, treatment approach and service delivery setting.

Thus, while the overall question is the same, the particulars vary:

“Does FIT work (with people in recovery for drug and alcohol problems, those with bipolar illness or schizophrenia, in crisis settings, group or family therapy, long term, inpatient or residential care)?

Occasionally, someone will report having read a study indicating FIT either did not work or made matters worse when used with certain types of clients (1) or in particular settings (2).

While I have posted detailed responses to specific studies published over the last couple of years (3), the near limitless number of ways questions of efficacy can be parsed ultimately renders such an approach clinically and pragmatically useless. Think of the panoply of potential parameters one would need to test. The latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders alone contains 297 diagnoses. Meanwhile, more than a decade ago, Scientific American identified 500 different types of psychotherapy. If history is a reliable guide, the number of approaches has most certainly increased by now. Add to that an ever evolving number of settings in which treatment takes place — most recently online — and the timeline for answering even the most basic questions quickly stretches to infinity.

So, returning to the question, “how best to decide whether to use FIT with ‘this or that’ client, treatment approach, or service setting?”

That’s the subject of my latest FIT TIP: Does FIT work with all Clients?

As promised, every 10 days or so, I’ve released a brief video providing practical guidance for optimzing your use of feedback in treatment. To date, these have addressed:

How to solicit clinically useful feedback

How to use client feedback to improve effectiveness

Identifying the best electronic FIT outcome system for you

What to do when your client is not making progress

Should you start FIT with established clients

OK, that’s it for now! Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

P.S.: Registration for the next FIT Implementation Online intensive is open. If you or your agency are thinking about or beginning to implement FIT, this is the event to attend. In this highly interactive training, you will learn evidence-based steps for ensuring success.

Managing the next Pandemic

I know, I know. You’re thinking, “A post about the next pandemic?!”

Some will insist, “We’re not done with the current one!” Others will, with the wave of a hand counter, “I’m so tired of this conversation, let’s move on. How about sushi for lunch?”

Now, however, is the perfect time to assess what happened and how matters should be handled in the next global emergency.

Scientists are already on the case. A recent study conducted by the University of Manchester and Imperial College London analyzed the relative effects of different non-pharmacological interventions aimed at controlling the spread of COVID-19. The investigation is notable for both its scope and rigor, analyzing data from 130 countries and accounting for date and strictness of implementation! The results are sure to surprise you. For example, consistent with my own, simple analysis of US state-by-state data published in the summer of 2020, researchers found, “no association between mandatory stay-at-home interventions on cross-country Covid-19 mortality after adjusting for other non-pharmaceutical interventions concurrently introduced.” Read for yourself what approaches did make a difference.

One non-pharmacological intervention that was not included in the analysis was the involvement of “human factors” experts — sociologists, anthropologists, psychologist, implementation scientists — in the development and implementation of COVID mitigation efforts. Indeed, those leading the process treated the last two years like a virus problem rather than a human management problem. The results speak for themselves. Beyond the division and death, the US is experiencing a dramatic mental health crisis, especially among our nation’s youth.

Which brings me to the latest edition of The Book Case — the podcast I do together with my friend and colleague Dr. Dan Lewis. In it, we consider two books with varying perspectives on the outbreak of COVID-19. As acknowledged at the outset of this post, I understand you may already have made up your mind. Whatever you’ve decided, I believe these two books will give you pause to reconsider and refine your thinking.

That’s all for now. Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Effectiveness

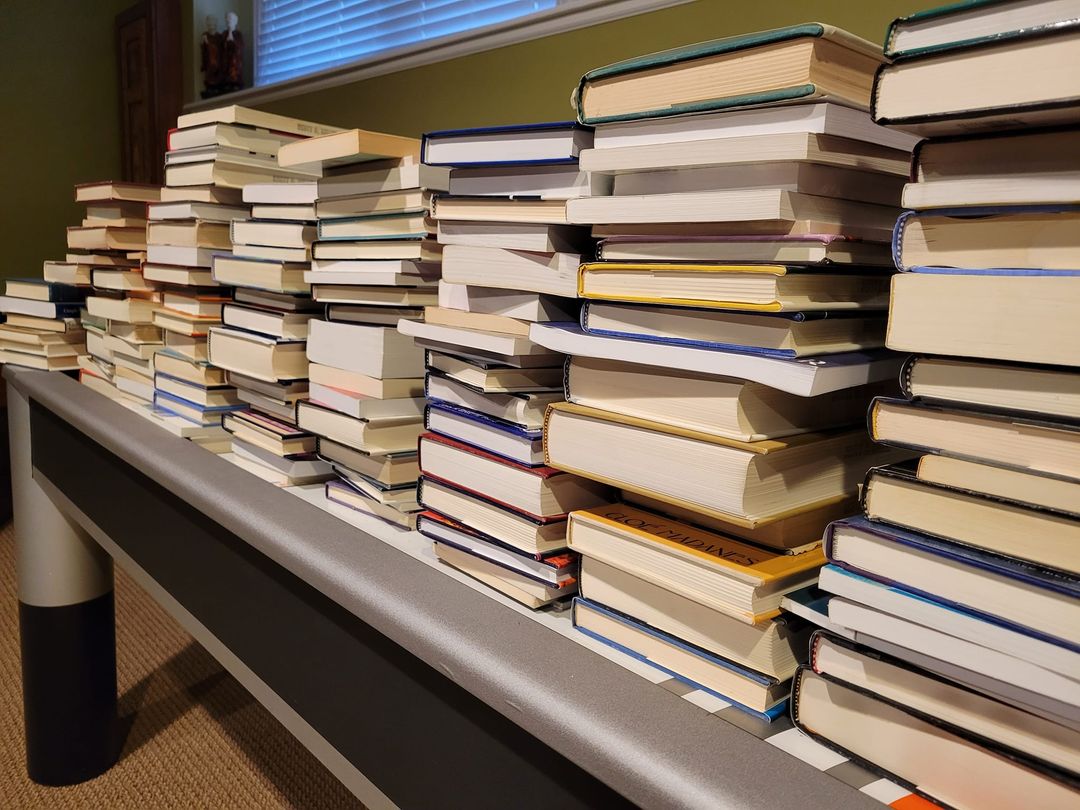

The Most Important Psychotherapy Book

Late last year, I began a project I’d been putting off for a long while: culling my professional books. I had thousands. They filled the shelves in both my office and home. To be sure, I did not collect for the sake of collecting. Each had been important to me at some time, served some purpose, be it a research or professional development project — or so I thought.

I contacted several local bookstores. I live in Chicago — a big city with many interesting shops and loads of clinicians. I also posted on social media. “Surely,” I was convinced, “someone would be interested.” After all, many were classics and more than a few had been signed by the authors.

I wish I had taken a selfie when the manager of one store told me, “These are pretty much worthless.” And no, they would not take them in trade or as a donation. “We’d just put them in the dumpster out back anyway,” they said with a laugh, “no one is interested.”

Honestly, I was floored. I couldn’t even give the books away!

The experience gave me pause. However, over a period of several months, and after much reflection, I gradually (and grudgingly) began to agree with the manager’s assessment. The truth was very few — maybe 10 to 20 — had been transformative, becoming the reference works I returned to time and again for both understanding and direction in my professional career.

Among that small group, one volume clearly stands out. A book I’ve considered my “secret source” of knowledge about psychotherapy, The Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. Beginning in the 1970’s, every edition has contained the most comprehensive, non-ideological, scientifically literate review of “what works” in our field.

Why secret? Because so few practitioners have ever heard of it, much less read it. Together with my colleague Dr. Dan Lewis, we review the most current, 50th anniversary edition. We also cover Ghost Hunter, a book about William James’ investigation of psychics and mediums.

What do these two books have in common? In a word, “science.” Don’t take my word for it, however. Listen to the podcast or video yourself!

Until next time, all the best!

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Study Shows FIT Improves Effectiveness by 25% BUT …

“Why don’t more therapists do FIT?” a grad student asked me during a recent consultation. Seated nearby in the room were department managers, supervisors, and many experienced practitioners.

“Well,” I said, queuing up my usual, diplomatic answer, “Feedback informed treatment is a relatively new idea, and the number of therapists doing it is growing.”

Unpersuaded, the student persisted, “Yeah, but with research showing such positive results, seems like ethically everyone should be doing FIT. What’s all the hesitance about?”

What’s that old expression? Out of the mouths of babes . . .

Truth is, a large, just released study showed FIT — specifically, the routine monitoring of outcome and relationship with the Outcome and Session Rating Scales — improved effectiveness by 25% over and above usual treatment services (1).

TWENTY-FIVE PERCENT!

In a second, pilot study conducted in a forensic psychiatric setting, use of the ORS and SRS dramatically reduced dropout rates (2).

What other clinical practice/technique can claim similar impacts on outcome and retention in mental health services?

Needless to say, perhaps, the student’s comments were more pointed. Use of FIT at the agency was decidedly uneven. Despite being a “clinical standard” for more than two years, many on staff — practitioners and supervisors alike — were not using the tools, or had started and then, just as quickly, stopped.

Here’s where the recent study might offer some help. The impact of FIT notwithstanding, researchers Bram Bovendeerd and colleagues found its use in routine practice was easily derailed. In their own words, they observe “implementation is challenging … and requires a careful plan of action.”

Even then, fate can intervene.

In their next paper, they describe how, even when organizational culture is receptive to FIT, contextual variables can get in the way. At one clinic, for example, it was the unexpected illness of a key staff member leaving everyone else to take up the slack. Curiously, when asked to explain the decline in use of the measures that followed, the therapists did not cite the increase in workload. Rather, in what appears to be a classic example of attempting to reduce cognitive dissonance — we know using the measures work, but we’re not doing it anyway — they developed and expressed doubts about the validity of the measures! Anyway, loads more interesting insights in the interview (below) I did with the lead researcher not long ago.

We’ll be addressing these and other implementation challenges at the next FIT Implementation coming up in August. Registration is open. Generally, the training sells out a month or more in advance. Click here for more information or to register.

Until next time, please share your thoughts in a comment.

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Seeing What Others Miss

It’s one of my favorite lines from one of my all time favorite films. Civilian Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) accompanies a troop of “colonial marines” to LV-426. Contact with the people living and working on the distant exomoon has been lost. A formidable life form is suspected. The Alien. Ripley is on board as an advisor. The only person that’s ever met the creature. The lone survivor of a ship whose crew was decimated hours after first contact.

It’s one of my favorite lines from one of my all time favorite films. Civilian Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) accompanies a troop of “colonial marines” to LV-426. Contact with the people living and working on the distant exomoon has been lost. A formidable life form is suspected. The Alien. Ripley is on board as an advisor. The only person that’s ever met the creature. The lone survivor of a ship whose crew was decimated hours after first contact.

On arrival, Ripley briefs the team. Her description and warnings are met with a mixture of determination and derision by the tough, experienced, highly-trained, and well-equipped soldiers. On touch down, the group immediately jumps into action. First contact does not go well. Confidence quickly gives way to chaos and confusion. Not only do many die, but the actions they take to defend themselves inadvertently damages a nuclear reactor.

If Ripley and the small group that remains hope to survive, they must get off the planet as soon as possible. With senior leaders out of commission,  command decisions fall to a lowly corporal named, Dwayne Hicks. His team is tired and facing overwhelming odds. It’s then he utters the line. “Hey, listen,” he says, “We’re all in strung out shape, but stay frosty, and alert …”.

command decisions fall to a lowly corporal named, Dwayne Hicks. His team is tired and facing overwhelming odds. It’s then he utters the line. “Hey, listen,” he says, “We’re all in strung out shape, but stay frosty, and alert …”.

Stay frosty and alert.

Sage counsel –advice which, had it been heeded from the very outset of the journey, would likely have changed the course of events — but also exceedingly difficult to do. Sounds. Smells. Flavors. Touch. Motion. Attention. Most behaviors. Once we become accustomed to them, they disappear from consciousness.

Said another way, experience dulls the senses. Except when it doesn’t. Turns out, some are less prone to habituation.

In his study of highly effective psychotherapists, for example, my colleague Dr. Daryl Chow (2014), found, “the number of times therapists were surprised by clients’ feedback … was … a significant predictor of client outcome” (p. xiii). Turns out, highly effective therapists frequently see something important in what average practitioners conclude is simply, “more of the same.” It should come as no surprise then that a large body of evidence finds no correlation between therapist effectiveness and their age, training, professional degree or certification, case load, or amount of clinical experience (1, 2).

Staying “frosty and alert” is the subject of Episode 5 of The Book Case Podcast. Together with my colleague, Dr. Dan Lewis, we review 3 new books, each organized around overcoming the natural human tendency to develop attentional biases and blind spots. Be sure and leave a comment after listening.

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

P.S.: As the Spring workshops in feedback-informed treatment (FIT) are sold out, registration is now open for the Summer 2022 events.

Reducing Dropout and Unplanned Terminations in Mental Health Services

Being a mental health professional is a lot like being a parent.

Please read that last statement carefully before drawing any conclusions!

I did not say mental health services are similar to parenting. Rather, despite their best efforts, therapists, like parents, routinely feel they fall short of their hopes and objectives. To be sure, research shows both enjoy their respective roles (1, 2). That said, they frequently are left with the sense that no matter how much they do, its never good enough. A recent poll found, for example 60% parents feel they fail their children in first years of life. And given the relatively high level of turnover on a typical clinician’s caseload — with a worldwide average of 5 to 6 sessions — what is therapy if not a kind of Goundhog Day repetition of being a new parent?

For therapists, such feelings are compounded by the number of clients who, without notice or warning, stop coming to treatment. Besides the obvious impact on productivity and income, the evidence shows such unplanned endings negatively impact clinicians’ self worth, ranking third among the top 25 most stressful client behaviors (3, p. 15).

Recent, large scale meta-analytic studies indicate one in five, or 20% (4) of clients, dropout of care — a figure that is slightly higher for adolescents and children (5). However, when defined as “clients who discontinue unilaterally without experiencing a reliable or clinically significant improvement in the problem that originally led them to seek treatment,” the rate is much higher (6)!

Feeling “not good enough” yet?

By the way, if you are thinking, “that’s not true of my caseload as hardly any of the people I see, dropout” or “my success rate is much higher than the figure just cited,” recall that parent who always acts as though their child is the cutest, smartest or most talented in class. Besides such behavior being unbecoming, it often displays a lack of awareness of the facts.

By the way, if you are thinking, “that’s not true of my caseload as hardly any of the people I see, dropout” or “my success rate is much higher than the figure just cited,” recall that parent who always acts as though their child is the cutest, smartest or most talented in class. Besides such behavior being unbecoming, it often displays a lack of awareness of the facts.

So, turning to the evidence, data indicate therapists routinely overestimate their effectiveness, with a staggering 96% ranking their outcomes “above average (7)!” And while the same “rose colored glasses” may cause us to underestimate the number of clients who terminate without notice, a more troubling reality may be the relatively large number who don’t dropout despite experiencing no measurable benefit from our work with them– up to 25%, research suggests.

What to do?

As author Alex Dumas once famously observed, “Nothing succeeds like success.” And when it comes addressing dropout, a recent, independent meta-analysis of 58 studies involving nearly 22,000 clients found Feedback-Informed Treatment (FIT) resulted in a 15% reduction in the number people who end psychotherapy without benefit (8). The same study — and another recent one (9) –documented FIT helps therapists respond more effectively to clients most at risk of staying for extended periods of time without benefit.

Will FIT prevent you from ever feeling “not good enough” again? Probably not. But as most parents with grown children say, “looking back, it was worth it.”

OK, that’s it for now,

Scott

Scott D. Miller Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

P.S.: If you are looking for support with your implementation of Feedback-Informed Treatment in your practice or agency, join colleagues from around the world in our upcoming online trainings.

Three Common Misunderstandings about Deliberate Practice for Therapists

Deliberate Practice is hot. Judging from the rising number of research studies, workshops, and social media posts, it hard to believe the term did not appear in the psychotherapy literature until 2007.

Deliberate Practice is hot. Judging from the rising number of research studies, workshops, and social media posts, it hard to believe the term did not appear in the psychotherapy literature until 2007.

The interest is understandable. Among the various approaches to professional development — supervision, continuing education, personal therapy — the evidence shows deliberate practice is the only one to result in improved effectiveness at the individual therapist level.

Devoting time to rehearsing what one wants to improve is hardly a novel idea. Any parent knows it to be true and has said as much to their kids. Truth is, references to enhancing one’s skills and abilities through focused effort date back more than two millennia. And here is where confusion and misunderstanding begin.

- Clinical practice is not deliberate practice. If doing therapy with clients on a daily basis were the same as engaging in deliberate practice, therapists would improve in effectiveness over the course of their careers. Research shows they do not. Instead, confidence improves. Let that sink in. Outcomes remain flat but confidence in our abilities continuously increases. It’s a phenomenon researchers term “automaticity” — the feeling most of us associate with having “learned” to do something –where actions are carried out without much conscious effort. One could go so far as to say clinical practice is incompatible with deliberate practice, as the latter, to be effective, must force us to question what we do without thinking.

- Deliberate practice is not a special set of techniques. The field of psychotherapy has a long history of selling formulaic approaches. Gift-wrapped in books, manuals, workshops, and webinars, the promise is do this — whatever the “this” is — and you will be more effective. Decades of research has shown these claims to be empty. By contrast, deliberate practice is not a formula to be followed, but a form. As such, the particulars will vary from person to person depending on what each needs to learn. Bottom line: beware pre-packaged content.

- Applying deliberate practice to mastering specific treatment models or techniques. Consider a recent study out of the United Kingdom (1). There, like elsewhere, massive amounts of money have been spent training clinicians to use cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The expenditure is part of a well-intentioned government program aimed at improving access to effective mental health services (2). Anyway, in the study, clinicians participated in a high intensity course that included more than 300 hours of training, supervision, and practice. Competence in delivering CBT was assessed at regular intervals and shown to improve significantly throughout the training. That said, despite the time, money, and resources devoted to mastering the approach, clinician effectiveness did not improve. Why? Contrary to common belief, competence in delivering specific treatment protocols contributes a negligible amount to the outcome of psychotherapy. As common sensical as it likely sounds, to have an impact, whatever we practice must target factors have leverage on outcome.

My colleague, Daryl Chow and I, have developed a tool for helping practitioners develop an effective deliberate practice plan.  Known as the “Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activities” (TDPA), it helps you identify aspects of your clinical performance likely to have the most impact on improving your effectiveness. Step-by-step instructions walk you through the process of assessing your work, setting small individualized learning objectives, developing practice activities, and monitoring your progress. As coaching is central to effective deliberate practice, a version of the tool is available for your supervisor or coach to complete. Did I mention, its free? Click here to download the TDPA contained in the same packet as the Outcome and Session Rating Scales. While your are at it, join our private, online discussion group where hundreds of clinicians around the world meet, support one another, and share experiences and ideas.

Known as the “Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activities” (TDPA), it helps you identify aspects of your clinical performance likely to have the most impact on improving your effectiveness. Step-by-step instructions walk you through the process of assessing your work, setting small individualized learning objectives, developing practice activities, and monitoring your progress. As coaching is central to effective deliberate practice, a version of the tool is available for your supervisor or coach to complete. Did I mention, its free? Click here to download the TDPA contained in the same packet as the Outcome and Session Rating Scales. While your are at it, join our private, online discussion group where hundreds of clinicians around the world meet, support one another, and share experiences and ideas.

OK, that’s it for now. All the best,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

P.S.: Improve your ability to deliver effective presentations online or in-person at the upcoming “Training of Trainers” workshop. This event is held only once, every two years — this time, online!

Feedback Informed Treatment in Statutory Services (Child Protection, Court Mandated)

“We don’t do ‘treatment,’ can we use FIT?”

“We don’t do ‘treatment,’ can we use FIT?”

It’s a question that comes up with increasing frequency as use of the Outcome and Session Rating Scales in the helping professions spreads around the globe and across diverse service settings.

When I answer an unequivocal, “yes,” the asker often responds as though I’d not heard what they said.

Speaking slowly and enunciating, “But Scott, we don’t do “t r e a t m e n t.‘” Invariably, they then clarify, “We do child protection,” or “We’re not therapists, we are case managers,” or providers in any of a large number of supportive, criminal justice, or other statutory social services.

How “treatment” became synonymous with psychotherapy (and other medical procedures) is a mystery to me. The word, as Merriam-Webster defines it, is merely the way we conduct ourselves — our specific manner, actions and behaviors — towards others.

With this definition in mind, working “feedback-informed” simply means interacting with people as though their experience of the service is both  primary and consequential. The challenge, I suppose, is how to do this when lives may be at risk (e.g., child protection, probation and parole), or when rules and regulations prescribe (or proscribe) provider and agency actions irrespective of how service users feel or what they prefer.

primary and consequential. The challenge, I suppose, is how to do this when lives may be at risk (e.g., child protection, probation and parole), or when rules and regulations prescribe (or proscribe) provider and agency actions irrespective of how service users feel or what they prefer.

Over the last decade, many governmental and non-governmental organizations have succeeded in making statutory services feedback-informed — and the results are impressive. For recipients, more engagement and better outcomes. For providers, less burnout, job turnover, and fewer sick days.

I had the opportunity to speak with the members and managers of one social service agency — Gladsaxe Kommune in Denmark — this last week. They described the ups, downs, and challenges they faced — including retraining staff, seeking variances to existing laws from authorities, — while working to transform agency practice and culture. If you work in this sector, I know you’ll find their experience both inspiring and practical. You can find the video below. Another governmental agency has created a step-by-step guide (in English) for implementing feedback informed treatment (FIT) in statutory service settings. It’s amazingly detailed and comprehensive. It’s also free. To access, click here.

Cliff note version of the results of implementing FIT in statutory services?

- 50% fewer kids placed outside the home

- 100% decrease in complaints filed by families against social service agencies and staff

- 100% decrease in staff turnover and sick days

OK, that’s it for now. Please leave a comment. If you, or your agency, is considering implementing FIT, please join us for the two-day intensive training in August. This time around, you can participate without leaving home as the entire workshop will be held online. For more information, click on the icon below.

All the best,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Do We Learn from Our Clients? Yes, No, Maybe So …

When it comes to professional development, we therapists are remarkably consistent in opinion about what matters. Regardless of experience level, theoretical preference, professional discipline, or gender identity, large, longitudinal studies show “learning from clients” is considered the most important and influential contributor (1, 2). Said another way, we believe clinical experience leads to better, increasingly effective performance in the consulting room.

When it comes to professional development, we therapists are remarkably consistent in opinion about what matters. Regardless of experience level, theoretical preference, professional discipline, or gender identity, large, longitudinal studies show “learning from clients” is considered the most important and influential contributor (1, 2). Said another way, we believe clinical experience leads to better, increasingly effective performance in the consulting room.

As difficult as it may be to accept, the evidence shows we are wrong. Confidence, proficiency, even knowledge about clinical practice, may improve with time and experience, but not our outcomes. Indeed, the largest study ever published on the topic — 6500 clients treated by 170 practitioners whose results were tracked for up to 17 years — found the longer therapists were “in practice,” the less effective they became (3)! Importantly, this result remained unchanged even after researchers controlled for several patient, caseload, and therapist-level characteristics known to have an impact effectiveness.

Only two interpretations are possible, neither of them particularly reassuring. Either we are not learning from our clients, or what we claim to be learning doesn’t improve our ability to help them. Just to be clear, the problem is not a lack of will. Therapists, research shows, devote considerable time, effort, and resources to professional development efforts (4). Rather, it appears the way we’ve approached the subject is suspect.

Consider the following provocative, but evidence-based idea. Most of the time, there simply is nothing to learn from a particular client  about how to improve our craft. Why? Because so much of what affects the outcome of individual clients at any given moment in care is random — that is, either outside of our direct control or not part of a recurring pattern of therapist errors. Extratherapeutic factors, as influences are termed, contribute a whopping 87% to outcome of treatment (5, 6). Let that sink in.

about how to improve our craft. Why? Because so much of what affects the outcome of individual clients at any given moment in care is random — that is, either outside of our direct control or not part of a recurring pattern of therapist errors. Extratherapeutic factors, as influences are termed, contribute a whopping 87% to outcome of treatment (5, 6). Let that sink in.

The temptation to draw connections between our actions and particular therapeutic results is both strong and understandable. We want to improve. To that end, the first step we take — just as we counsel clients — is to examine our own thoughts and actions in an attempt to extract lessons for the future. That’s fine, unless no causal connection exists between what we think and do, and the outcomes that follow … then, we might as well add “rubbing a rabbit’s foot” to our professional development plans.

So, what can we to do? Once more, the answer is as provocative as it is evidence-based. Recognizing the large role randomness plays in the outcome of clinical work, therapists can achieve better results by improving their ability to respond in-the-moment to the individual and their unique and unpredictable set of circumstances. Indeed, uber-researchers Stiles and Horvath note, research indicates, “Certain therapists are more effective than others … because [they are] appropriately responsive … providing each client with a different, individually tailored treatment” (7, p. 71).

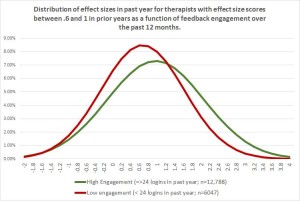

What does improving responsiveness look like in real world clinical practice? In a word, “feedback.” A clever study by Jeb Brown and Chris Cazauvielh found, for example, average therapists who were more engaged with the feedback their clients provided — as measured by the number of times they logged into a computerized data gathering program to view their results — in time became more effective than their less engaged peers (8). How much more effective you ask? Close to 30% — not a bad “return on investment” for asking clients to answer a handful of simple questions and then responding to the information they provide!

What does improving responsiveness look like in real world clinical practice? In a word, “feedback.” A clever study by Jeb Brown and Chris Cazauvielh found, for example, average therapists who were more engaged with the feedback their clients provided — as measured by the number of times they logged into a computerized data gathering program to view their results — in time became more effective than their less engaged peers (8). How much more effective you ask? Close to 30% — not a bad “return on investment” for asking clients to answer a handful of simple questions and then responding to the information they provide!

If you haven’t already done so, click here to access and begin using two, free, standardized tools for gathering feedback from clients. Next, ioin our free, online community to get the support and inspiration you need to act effectively and creatively on the feedback your clients provide — hundreds and hundreds of dedicated therapists working in diverse settings around the world support each other daily on the forum and are available regardless of time zone.

And here’s a bonus. Collecting feedback, in time, provides the very data therapists need to be able to sort random from non-random in their clinical work, to reliably identify when they need to respond and when a true opportunity for learning exists. Have you heard or read anything about “deliberate practice?” Since first introducing the term to the field in our 2007 article, Supershrinks, it’s become a hot topic among researchers and trainers. If you haven’t yet, chances are you will soon be seeing books and videos offering to teach how to use deliberate practice for mastering any number of treatment methods. The promise, of course, is better outcomes. Critically, however, if training is not targeted directly to patterns of action or inaction that reliably impact the effectiveness of your individual clinical performance in negative ways, such efforts will, like clinical experience in general, make little difference.

If you are already using standardized tools to gather feedback from clients, you might be interested in joining me and my colleague Dr. Daryl Chow  for upcoming, web-based workshop. Delivered weekly in bite-sized bits, we’ll not only help you use your data to identify your specific learning edge, but work with you to develop an individualized deliberate practice plan. You go at your own pace as access to the course and all training materials are available to you forever. Interested? Click here to read more or sign up.

for upcoming, web-based workshop. Delivered weekly in bite-sized bits, we’ll not only help you use your data to identify your specific learning edge, but work with you to develop an individualized deliberate practice plan. You go at your own pace as access to the course and all training materials are available to you forever. Interested? Click here to read more or sign up.

OK, that’s it for now. Until next time, wishes of health and safety, to you, your colleagues, and family.

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Making Sense of Client Feedback

I have a guilty confession to make. I really like Kitchen Nightmares. Even though the show finished its run six L O N G years ago, I still watch it in re-runs. The concept was simple. Send one of the world’s best known chefs to save a failing restaurant.

I have a guilty confession to make. I really like Kitchen Nightmares. Even though the show finished its run six L O N G years ago, I still watch it in re-runs. The concept was simple. Send one of the world’s best known chefs to save a failing restaurant.

Each week a new disaster establishment was featured. A fair number were dives — dirty, disorganized messes with all the charm and quality of a gas station lavatory. It wasn’t hard to figure out why these spots were in trouble. Others, by contrast, were beautiful, high-end eateries whose difficulties were not immediately obvious.

Of course, I have no idea how much of what we viewers saw was real versus contrived. Regardless, the answers owners gave whenever Ramsey asked for their assessment of the restaurant never failed to surprise and amuse. I don’t recall a single episode where the owners readily acknowledged having any problems, other than the lack of customers! In fact, most often they defended themselves, typically rating their fare “above average,” — a 7 or higher on a scale from 1 to 10.

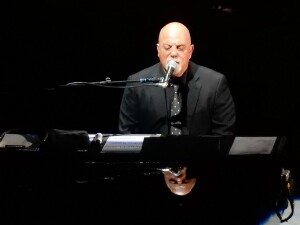

Contrast the attitude of these restaurateurs with pop music icon Billy Joel. When journalist Steve Croft asked him why he  thought he’d been so successful, Joel at first balked, eventually answering, “Well, I have a theory, and it may sound a little like false humility, but … I actually just feel that I’m competent.” Whether or not you are a fan of Joel’s sound, you have to admit the statement is remarkable. He is one of the most successful music artists in modern history, inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, winning a Grammy Legend Award, earning four number one albums on the Billboard 200, and consistently filling stadiums of adoring fans despite not having released a new album since 1993! And yet, unlike those featured on Kitchen Nightmares, he sees himself as merely competent, adding “when .. you live in an age where there’s a lot of incompetence, it makes you appear extraordinary.”

thought he’d been so successful, Joel at first balked, eventually answering, “Well, I have a theory, and it may sound a little like false humility, but … I actually just feel that I’m competent.” Whether or not you are a fan of Joel’s sound, you have to admit the statement is remarkable. He is one of the most successful music artists in modern history, inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, winning a Grammy Legend Award, earning four number one albums on the Billboard 200, and consistently filling stadiums of adoring fans despite not having released a new album since 1993! And yet, unlike those featured on Kitchen Nightmares, he sees himself as merely competent, adding “when .. you live in an age where there’s a lot of incompetence, it makes you appear extraordinary.”

Is humility associated with success? Well, turns out, it is a quality possessed by highly effective effective therapists. Studies not only confirm “professional self-doubt” is a strong predictor of both alliance and outcome in psychotherapy but actually a prerequisite for acquiring therapeutic expertise (1, 2). To be clear, I’m not talking about debilitating diffidence or, as is popular in some therapeutic circles, knowingly adopting a “not-knowing” stance. As researchers Hook, Watkins, Davis, and Owen describe, its about feedback — specifically, “valuing input from the other (or client) … and [a] willingness to engage in self-scrutiny.”

Low humility, research shows, is associated with compromised openness (3). Sound familiar? It is the most common reaction of owners featured on Kitchen Nightmares. Season 5 contained two back-to-back episodes featuring Galleria 33, an Italian restaurant in Boston, Massachusetts. As is typical, the show starts out with management expressing bewilderment about their failing business. According to them, they’ve tried everything — redecorating, changing the menu, lowering prices. Nothing has worked. To the viewer, the problem is instantly obvious: they don’t take kindly to feedback. When one customer complains their meal is “a little cold,” one of the owners becomes enraged. She first argues with Ramsey, who agrees with the customer’s assessment, and then storms over to the table to confront the diner. Under the guise of “just being curious and trying to understand,” she berates and humiliates them. It’s positively cringeworthy. After numerous similar complaints from other customers — and repeated, uncharacteristically calm, corrective feedback from Ramsey — the owner experiences a moment of uncertainty. Looking directly into the camera she asks, “Am I in denial?” The thought is quickly dismissed. The real problem, she and the co-owner decide, is … (wait for it) …

Ramsey and their customers! Is anyone surprised the restaurant didn’t survive?

Such dramatic examples aside, few therapists would dispute the importance of feedback in psychotherapy. How do I know? I’ve meet thousands over the last two decades as I traveled the world teaching about feedback-informed treatment (FIT). Research on implementation indicates a far bigger challenge is making sense of the feedback one receives (4, 5, 6) Yes, we can (and should) speak with the client — research shows therapists do that about 60% of the time when they receive negative feedback. However, like an unhappy diner in an episode of Kitchen Nightmares, they may not know exactly what to do to fix the problem. That’s where outside support and consultation can be critical. Distressingly, research shows, even when clients are deteriorating, therapists consult with others (e.g., supervisors, colleagues, expert coaches) only 7% of time.

Such dramatic examples aside, few therapists would dispute the importance of feedback in psychotherapy. How do I know? I’ve meet thousands over the last two decades as I traveled the world teaching about feedback-informed treatment (FIT). Research on implementation indicates a far bigger challenge is making sense of the feedback one receives (4, 5, 6) Yes, we can (and should) speak with the client — research shows therapists do that about 60% of the time when they receive negative feedback. However, like an unhappy diner in an episode of Kitchen Nightmares, they may not know exactly what to do to fix the problem. That’s where outside support and consultation can be critical. Distressingly, research shows, even when clients are deteriorating, therapists consult with others (e.g., supervisors, colleagues, expert coaches) only 7% of time.

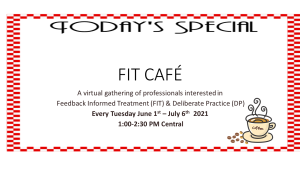

Since late summer, my colleagues and I at the International Center for Clinical Excellence have offered a series of intimate, virtual gatherings of mental health professionals. Known as the FIT Cafe, the small group (10 max) gets together once a week to finesse their FIT-related skills and process client feedback. It’s a combination of support, sharing, tips, strategizing, and individual consultation. As frequent participant, psychologist Claire Wilde observes, “it has provided critical support for using the ORS and SRS to improve my therapeutic effectiveness with tricky cases, while also learning ways to use collected data to target areas for professional growth.”

The next series is fast approaching, a combination of veterans and newbies from the US, Canada, Europe, Scandinavia, and Australia. Learn more or register by clicking here or on the icon to the right.

Not ready for such an “up close and personal” experience? Please join the ICCE online discussion forum. It’s free. You can connect with knowledgeable and considerate colleagues working to implement FIT and deliberate practice in their clinical practice in diverse settings around the world.

OK, that’s it for now. Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Umpires and Psychotherapists

Criticizing umpires is as much a part of watching baseball as eating hotdogs and wearing team jerseys on game day. The insults are legion, whole websites are dedicated to cataloging them:

Criticizing umpires is as much a part of watching baseball as eating hotdogs and wearing team jerseys on game day. The insults are legion, whole websites are dedicated to cataloging them:

“Open your eyes!”

“Wake up, you are missing a great game!”

“Your glasses fogged up?”

“Have you tried eating more carrots?”

“I’ve seen potatoes with better eyes!”

“Hey Ump, how many fingers am I holding up?

Are you “seeing” a common theme here?

And interestingly, the evidence indicates fans have reason to question the judgement and visual acuity of most umpires. A truly massive study of nearly 4 million pitches examined the accuracy of their calls over 11 regular seasons. I didn’t know this, but it turns out, all major league stadiums are equipped with fancy cameras which track every ball thrown from mound to home plate. Using this data, researchers found “botched calls and high error rates are rampant.” How many you ask? A staggering 34,246 incorrect calls in the 2018 season alone! It gets worse. When the pressure was on — a player at bat, for example, with two strikes — umpire errors skyrocket, occurring nearly one-third of the time. Surely, the “umps” improve with time an experience? Nope. In terms of accuracy, youth and inexperienced win out every time!

Now, let me ask, are your “ears burning” yet?

Turns out, umpires and psychotherapists share some common traits. So, for example, despite widespread belief to the contrary, clinicians are not particularly good at detecting deterioration in clients. How bad are we? In one study, therapists correctly identified clients who worsen in their care a mere two-and-a-half percent of the time (1)! Like umpires, “we call ’em as we see ’em.” We just don’t see them. And if you believe we improve with experience, think again. The largest study in the history of research on the subject — 170 practitioners treating 6500 clients over a 5 year period — reveals that what is true of umpires applies equally to clinicians. Simply put, on average, our outcomes decline the longer we are in the field.

If you are beginning to feel discouraged, hold on a minute. While the data clearly show umpires make mistakes, the same evidence documents most of their calls are correct. Similarly, therapists working in real world settings help the majority of their clients achieve meaningful change — between 64 and 74% in our database of thousands of clinicians and several million completed treatment episodes.

Still, you wouldn’t be too far “off base” were you to conclude, “room for improvement exists.”

Truth is, umpires and therapists are calling “balls and strikes” much the same way they did when Babe Ruth and Alfred Alder were key players. Solutions do exist. As you might guess, they are organized around using feedback to augment and improve individual judgement ability. So far, major league baseball (and its umpires) has resisted. In psychotherapy, evidence shows clients of therapists who formally and routinely solicit feedback regarding the quality of the therapeutic relationship and progress over time are twice as likely to experience improvement in treatment.

The measures are free for practitioners to use and available in 25+ languages. If you don’t have them, click here to register. You’ll likely need some support in understanding how to use them effectively. Please join the conversation with thousands of colleagues from around the world in the ICCE Discussion Forum. If you find yourself wanting to learn more, click on the icon below my name for information about our next upcoming intensive — online, by the way!

What more is there to say, except: BATTER UP!

Until next time, wishes for a safe and healthy Holiday season,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

BAD THERAPY

Are you guilty of it? A quick internet search turned up only 15 books on the subject. It’s strange, especially when you consider that between 5 and 10% of clients are actually worse off following treatment and an additional 35-40% experience no benefit whatsoever! (Yep, that’s nearly 50%)

And what about those numerous “micro-failures.” You know the ones I’m talking about? Those miniature ruptures, empathic missteps, and outright gaffs committed during the therapy hour. For example, seated opposite your client, empathic look glued to your face and suddenly you cannot remember your client’s name? Or worse, you call them by someone else’s. The point is, there’s a lot of bad therapy.

Why don’t we therapists talk about these experiences more often? Could it possibly be that we don’t know? Four years on, I can still remember the surprise I felt when Norwegian researcher, Jorgen Flor, found most therapists had a hard time recalling any clients they hadn’t helped.

One group does know — and recently, they’ve been talking their experiences! The Very Bad Therapy podcast is one of my favorites. After listening to sixty-some-odd episodes of clients exposing our shortcomings, I reached out to the podcast’s two fearless interviewers, clinicians Ben Fineman and Carrie Wiita, to learn what had motivated them to start the series in the first place and what, if anything, they’d learned along the way. Here’s what I promise: they have no shame (and its a good thing for us they don’t)!

OK, that’s it for now. Until next time, all the best,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

P.S.: For the first time ever, we’re offering the FIT Implementation Intensive Online. It’s one of the four courses required for certification as an ICCE FIT Trainer. As with our “in-person” events, we have an international faculty and strictly limit the number of participants to 40 to ensure the highest quality experience. Click here for more information or to register.

Does Teletherapy Work?

With the outbreak of the coronavirus, much of mental health service delivery shifted online. Regulations regarding payment and confidentiality were scaled back in an effort to deal with the unprecedented circumstances, allowing clinicians and their clients to meet virtually in order to reduce the spread of the illness.

With the outbreak of the coronavirus, much of mental health service delivery shifted online. Regulations regarding payment and confidentiality were scaled back in an effort to deal with the unprecedented circumstances, allowing clinicians and their clients to meet virtually in order to reduce the spread of the illness.

Getting Beyond the “Good Idea” Phase in Evidence-based Practice

The year is 1846. Hungarian-born physician Ignaz Semmelweis is in his first month of employment at Vienna General hospital when he notices a troublingly high death rate among women giving birth in the obstetrics ward. Medical science at the time attributes the problem to “miasma,” an invisible, poison gas believed responsible for a variety of illnesses.

Semmelweis has a different idea. Having noticed midwives at the hospital have a death rate six times lower than physicians, he concludes the prevailing theory cannot possibly be correct. The final breakthrough comes when a male colleague dies after puncturing his finger while performing an autopsy. Reasoning that contact with corpses is somehow implicated in the higher death rate among physicians, he orders all to wash their hands prior to interacting with patients. The rest is, as they say, history. In no time, the mortality rate on the maternity ward plummets, dropping to the same level as that of midwives.

Nowadays, of course, handwashing is considered a “best practice.” Decades of research show it to be the single most effective way to prevent the spread of infections. And yet, nearly 200 years after Semmewies’s life-saving discovery, compliance with hand hygiene among healthcare professionals remains shockingly low, with figures consistently ranging between 40 and 60% (1, 2). Bottom line: a vast gulf exists between sound scientific practices and their implementation in real world settings. Indeed, the evidence shows 70 to 95% of attempts to implement evidence-based strategies fail.

To the surprise of many, successful implementation depends less on disseminating “how to” information to practitioners than on establishing a culture supportive of new practices. In one study of hand washing, for example, when Johns Hopkins Hospital administrators put policies and structures in place facilitating an open, collaborative, and transparent culture among healthcare staff (e.g., nurses, physicians, assistants), compliance rates soared and infections dropped to zero!

on establishing a culture supportive of new practices. In one study of hand washing, for example, when Johns Hopkins Hospital administrators put policies and structures in place facilitating an open, collaborative, and transparent culture among healthcare staff (e.g., nurses, physicians, assistants), compliance rates soared and infections dropped to zero!

Feedback Informed Treatment (FIT) — soliciting and using formal client feedback to guide mental health service delivery — is another sound scientific practice. Scores of randomized clinical trials and naturalistic studies show it improves outcomes while simultaneously reducing drop out and deterioration rates. And while literally hundreds of thousands of practitioners and agencies have downloaded the Outcome and Session Rating Scales — my two, brief, feedback tools — since they were developed nearly 20 years ago, I know most will struggle to put them into practice in a consistent and effective way.

To be clear, the problem has nothing to do with motivation or training. Most are enthusiastic to start. Many invest significant time and money in training. Rather, just as with hand washing, the real challenge is creating the open, collaborative, and transparent workplace culture necessary to sustain FIT in daily practice. What exactly does such a culture look like and what actions can practitioners, supervisors, and managers take to facilitate its development? That’s the subject of our latest “how to” video by ICCE Certified Trainer, Stacy Bancroft. It’s packed with practical strategies tested in real world clinical settings.

We’ll cover the subject in even greater detail in the upcoming FIT Implementation Intensive — the only evidence-based training on implementing routine outcome monitoring available.

We’ll cover the subject in even greater detail in the upcoming FIT Implementation Intensive — the only evidence-based training on implementing routine outcome monitoring available.

For the first time ever, the training will be held ONLINE, so you can learn from the comfort and safety of your home. As with all ICCE events, we limit the number of participants to 40 to ensure each gets personalized attention. For more information or to register, click here.

OK, that’s it for now.

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

P.S.: Want to interact with FIT Practitioners around the world? Join the conversation here.

The Expert on Expertise: An Interview with K. Anders Ericsson

I can remember exactly where I was when I first “met” Swedish psychologist, K. Anders Ericsson. Several hours into a long, overseas flight, I discovered someone had left a magazine in the seat pocket. I never would have even given the periodical a second thought had I not seen all the movies onboard — many twice. Its target audience wasn’t really aimed at mental health professionals: Fortune.

I can remember exactly where I was when I first “met” Swedish psychologist, K. Anders Ericsson. Several hours into a long, overseas flight, I discovered someone had left a magazine in the seat pocket. I never would have even given the periodical a second thought had I not seen all the movies onboard — many twice. Its target audience wasn’t really aimed at mental health professionals: Fortune.

Bored, I mindlessly thumbed through the pages. Then, between articles about investing and pictures of luxury watches, was an article that addressed a puzzle my colleagues and I had been struggling to solve for some time: why were some therapists more consistently effective than others?

In 1974, psychologist David F. Ricks published the first study documenting the superior outcomes of a select group of practitioners he termed, “supershrinks.” Strangely, thirty-years would pass before another empirical analysis appeared in the literature.

The size and scope of the study by researchers Okiishi, Lambert, Nielsen, and Ogles (2003), dwarfed Rick’s, examining results from standardized measures  administered on an ongoing basis to over 1800 people treated by 91 therapists. The findings not only confirmed the existence of “supershrinks,” but showed exactly just how big the difference was between them and average clinicians. Clients of the most effective experienced a rate of improvement 10 times greater than the average. Meanwhile, those treated by the least effective, ended up feeling the same or worse than when they’d started — even after attending 3 times as many sessions! How did the best work their magic? The researchers were at a loss to explain, ending their article calling it a “mystery” (p. 372).

administered on an ongoing basis to over 1800 people treated by 91 therapists. The findings not only confirmed the existence of “supershrinks,” but showed exactly just how big the difference was between them and average clinicians. Clients of the most effective experienced a rate of improvement 10 times greater than the average. Meanwhile, those treated by the least effective, ended up feeling the same or worse than when they’d started — even after attending 3 times as many sessions! How did the best work their magic? The researchers were at a loss to explain, ending their article calling it a “mystery” (p. 372).

By this point, several years into the worldwide implementation of the outcome and session rating scales, we’d noticed (and, as indicated, were baffled by) the very same phenomenon. Why were some more effective? We pursued several lines of inquiry. Was it their technique? Didn’t seem to be. What about their training? Was it better or different in some way? Frighteningly, no. Experience level? Didn’t matter. Was it the clients they treated? No, in fact, their outcomes were superior regardless of who walked through their door. Could it be that some were simply born to greatness? On this question, the article in Fortune, was clear, “The evidence … does not support the [notion that] excelling is a consequence of possessing innate gifts.”

So what was it?

Enter K. Anders Ericsson. His life had been spent studying great performers in many fields, including medicine, mathematics, music, computer programming, chess, and sports. The best, he and his team had discovered, spent more time engaged in an activity they termed, “deliberate practice” (DP). Far from mindless repetition, it involved: (1) establishing a reliable and valid assessment of performance; (2) the identification of objectives just beyond an individual’s current level of ability; (3) development and engagement in exercises specifically designed to reach new performance milestones; (4) ongoing corrective feedback; and (5) successive refinement over time via repetition.

I can remember how excited I felt on finishing the article. The ideas made so much intuitive sense. Trapped in a middle seat, my row-mates on either side fast asleep, I resolved to contact Dr. Ericsson as soon as I got home.

Anders replied almost immediately, giving rise to a decade and a half of correspondence, mentoring, co-presenting, and friendship. And now he is gone. To say I am shocked is an understatement. I’d just spoken with him a few days prior to his death. He was in great spirits, forever helpful and supportive, full of insights and critical feedback. I will miss him — his warmth, encouragement, humility, and continuing curiosity. If you never met him, you can get a good sense of who he was from the interview I did with him two weeks ago. Let me know your thoughts in the comments below.

Until next time, I wish you health, peace, and progress.

Scott

Far from Normal: More Resources for Feedback Informed Treatment in the Time of COVID-19

I hope this post finds you, your loved ones, and colleagues, safe and healthy.

I hope this post finds you, your loved ones, and colleagues, safe and healthy.

What an amazing few weeks this has been. Daily life, as most of us know it, has been turned upside down. The clinicians I’ve spoken with are working frantically to adjust to the new reality, including staying abreast of rapidly evolving healthcare regulation and learning how to provide services online.

I cannot think of a time in recent memory when the need to adapt has more pressing. As everyone knows, feedback plays a crucial role in this process.

Last week, I reported a surge in downloads of the Outcome and Session Rating Scales (ORS & SRS), up 21% over the preceding three months. Independent, randomized controlled trials document clients are two and a half times more likely to benefit from therapy when their feedback is solicited via the measures and used to inform care. Good news, eh? Practitioners are looking for methods to enhance their work in these new and challenging circumstances. Only problem is the same research shows it takes time to learn to use the measures effectively — and that’s under the best or, at least, most normal of circumstances!

Given that we are far from normal, the team at the International Center for Clinical Excellence, in combination with longtime technology and continuing education partners, have been working to provide the resources necessary for practitioners to make the leap to online services. In my prior post, a number of tips were shared, including empirically-validating scripts for oral administration of the ORS and SRS as well as instructional videos for texting, email, and online use via the three, authorized FIT software platforms.

We are not done. Below, you will find two, new instructional videos from ICCE Certified Trainers, Stacy Bancroft and Brooke Mathewes. They provide step-by-step instructions and examples of how to administer the measures orally — a useful skill if you are providing services online or via the telephone.

Two additional resources:

- On April 15th at 5:00 p.m. CENTRAL time, I will be hosting a second, free online discussion for practitioners interested in feedback informed treatment and deliberate practice. Although all are welcome to join, the particular time has been chosen to accommodate colleagues in Australia, New Zealand, and Asia. To join, you must register. Here’s the link: https://zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_c5eousjqQRChSSQSj3AQZg.

- My dear colleague, Elizabeth Irias at Clearly Clinical, has made a series of podcasts about the COVID-19 pandemic available for free (including CE’s). What could be better than “earning while you are learning,” with courses about transitioning to online services and understanding the latest research on the psychological impact of the virus on clients.

OK, that’s it for now.

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Final Making Sense of Making Sense of Negative Research Results about Feedback Informed Treatment

“Everyone understands how a toilet works, don’t you?” ask cognitive scientists Sloman and Fernbach.

“Everyone understands how a toilet works, don’t you?” ask cognitive scientists Sloman and Fernbach.

The answer, according to their research, is likely no. Turns out, peoples’ confidence in their knowledge far outstrips their ability to explain how any number of simple, every day items work — a coffeemaker, zipper, bicycle and yes, a toilet. More troubling, as complexity increases, the problem only worsens. Thus, if you struggle to explain how glue holds two pieces of paper together — and most, despite being certain they can, cannot — good luck accounting for how an activity as complicated as psychotherapy works.

So pronounced is our inability to recognize the depth of our ignorance, the two researchers have given the phenomenon a name: the “Illusion of Explanatory Depth.” To be sure, in most instances, not being able to adequately and accurately explain isn’t a problem. Put simply, knowing how to make something work is more important in everyday life than knowing how it actually works:

- Push the handle on the toilet and the water goes down the drain, replaced by fresh water from the tank;

- Depress the lever on the toaster, threads of bare wire heat up, and the bread begins to roast;

- Replace negative cognitions with positive ones and depression lifts.

Simple, right?

Our limited understanding serves us well until we need to build or improve upon any one of the foregoing. In those instances, lacking true understanding,  we could literally believe anything — in the case of the toilet, a little man in the rowboat inside the tank makes it flush — and be just as successful. While such apparent human frailty might, at first pass, arouse feelings of shame or stupidity, truth is operating on a “need to know” basis makes good sense. It’s both pragmatic and economical. In life, you cannot possibly, and don’t really need to know everything.

we could literally believe anything — in the case of the toilet, a little man in the rowboat inside the tank makes it flush — and be just as successful. While such apparent human frailty might, at first pass, arouse feelings of shame or stupidity, truth is operating on a “need to know” basis makes good sense. It’s both pragmatic and economical. In life, you cannot possibly, and don’t really need to know everything.

And yet, therein lies the paradox: we passionately believe we do. That is, until we are asked to provide a detailed, step-by-step, scientifically sound accounting — only then, does humility and the potential for learning enter the picture.

When research on routine outcome monitoring (ROM) first began to appear, the reported impact on outcomes was astonishing. Some claimed it was the most important development in the field since the invention of psychotherapy! They were also quite certain how it worked: like a blood test, outcome and alliance measures enabled clinicians to check progress and make adjustments when needed. Voila!

Eight years ago, I drew attention to the assertions being made about ROM, warning “caution was warranted. ” It was not a bold statement, rather a reasoned one. After all, throughout the waning decades of the last millennium and into the present, proponents of cognitive (CT) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) had similarly overreached, claiming not only that their methods were superior in effect to all others, but that the mechanisms responsible were well understood. Both proved false. As I’ve written extensively on my blog, CT and CBT are no more effective in head to head comparisons with other approaches. More, studies dating back to 1996 have not found any of the ingredients, touted by experts as critical, necessary to success (1, 2, 3).

That’s why I was excited when researchers Mikeal, Gillaspy, Scoles, and Murphy (2016) published the first dismantling study of the Outcome and Session Rating Scales, showing that using the measures in combination, or just one or the other, resulted in similar outcomes. Some were dismayed by these findings. They wrote to me questioning the value of the tools. For me, however, it proved what I’d said back in 2012, “focusing on the measures misses the point.” Figure out why their use improves outcomes and we stop conflating features with causes, and are poised to build on what most matters.

That’s why I was excited when researchers Mikeal, Gillaspy, Scoles, and Murphy (2016) published the first dismantling study of the Outcome and Session Rating Scales, showing that using the measures in combination, or just one or the other, resulted in similar outcomes. Some were dismayed by these findings. They wrote to me questioning the value of the tools. For me, however, it proved what I’d said back in 2012, “focusing on the measures misses the point.” Figure out why their use improves outcomes and we stop conflating features with causes, and are poised to build on what most matters.

On this score, what do the data say? When it comes to feedback informed treatment, two key factors count:

- The therapist administering the measures; and

- The quality of the therapeutic relationship.

As is true of psychotherapy-in-general, the evidence indicates that who uses the scales is more important that what measures are used (1, 2). Here’s what we know:

- Therapists with an open attitude towards getting feedback reach faster progress with their patients;

- Clinicians able to create an environment in which clients provide critical (e.g., negative) feedback in the form of lower alliance scores early on in care have better outcomes (1, 2); and

- The more time a therapists spend consulting the data generated by routinely administering outcome and alliance measures, the greater their growth in effectiveness over time.

In terms of how FIT helps, two lines of research are noteworthy:

- In a “first of its kind” study, psychologist Heidi Brattland found that the strength of the therapeutic relationship improved

more over the course of care when clinicians used the Outcome and Session Rating Scales (ORS & SRS) compared to when they did not. Critically, such improvements resulted in better outcomes for clients, ultimately accounting for nearly a quarter of the effect of FIT.