Once upon a time, a nickel (the U.S. 5-cent coin) had value.

As a kid, I could get a generous scoop of ice cream at Sav-On, Big Hunk candy bar at Bock’s variety store, or a super-sized glazed doughnut at the Donut Man shop on Route 66.

At that time, a nickel was considered so valuable that when you wanted to imply something was worthless, you would say, “Yeah, that, and a nickel will get you a cup of coffee.” According to a post on Quora, the expression arose in the 1940’s when a cup typically cost five cents.

Along with, “I’m not going to hold my breath,” the expression was one my Dad sometimes used in response to me making any number of promises (e.g., clean my room, walk the dog, practice the piano or be nice to my younger brother).

I’m sure he hoped I’d follow through, much the same way we therapists believe growing clinical experience results in greater expertise and effectiveness. Why, otherwise, would so many of our websites feature “time in the chair” so prominently?

“I have over 15,000 hours of clinical experience,” says one. “I’ve been a psychotherapist for more than 20 years and have authored 5 best-selling books,” says another.

And yet, when such statements are considered in light of the evidence, it seems clear the most appropriate response is, “Yeah, and that plus $6.75 will get you a grande, soy, caramel macchiato at Starbucks.”

(The cost of a cup of coffee has obviously risen a bit since 1940)

Indeed, as I’ve reported in previous posts, research not only shows therapists do not improve with time and experience in the field, but on average become less effective (1, 2, 3, 4). Other studies document that students achieve outcomes on par or better than licensed professionals who supervise them (5, 6). Given such findings, it is more than a bit ironic that experience is associated with higher per hour fees (7) — increased rates which, it turns out, are tied to higher dropout rates!

Enter a new study by Bugatti and colleagues examining therapist dropout rates. Using data generated by more than 2,500 practitioners working with real clients in real world clinical settings, the researchers found therapists’ dropout rates increased the longer they were in practice.

You read that right.

Similar to the findings on effectiveness, therapist experience is not associated with better client retention rates. More, as noted previously, “therapists working with clients paying higher out-of-pocket fees have higher increases in client dropout over time.” Finally, in case you are wondering, caseload size did impact retention rates, but in a direction opposite to what most expect; specifically, therapists treating the most clients had the lowest dropout rates.

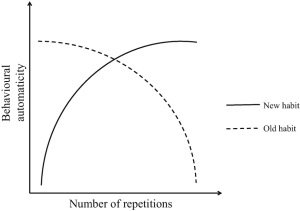

Bottom line? It’s time for the field to stop attributing benefits to clinical experience. Beyond the obvious ethical concerns, doing so actually prevents us from improving our effectiveness! A fundamental element of deliberate practice is challenging automaticity, or the lack of conscious control over and inability to make specific intentional adjustments to our behaviors that comes with … experience.

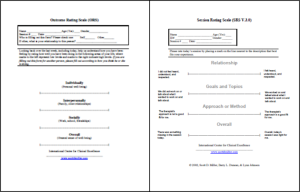

Raising awareness is the first step. To improve, we have to know where our actions and thinking fall short. Measuring and mapping our performance — as described in Better Results: Using Deliberate Practice to Improve Therapeutic Effectiveness and its companion volume, The Field Guide to Better Results — are two methods proven to help. The latest studies show, for example, both improved retention and effectiveness rates (~25%).

My colleauge and co-author, Daryl Chow, Ph.D., and I will be talking about these two methods (and the latest research findings reported here) at the next, online “Tuesdays with Daryl and Scott.” Held the last Tuesday of each month, the next one will be held on May 28th at 8 a.m. Central time.

No cost — not even a nickel — and you supply your own coffee.

Space is limited, however, so please click here to register and secure your spot.

ing Psychology.

ing Psychology.

e boundary between “belief in the process” and “denial of reality” is remarkably fuzzy. Hope is a significant contributor to outcome—accounting for as much as 30% of the variance in results. At the same time, it becomes toxic when actual outcomes are distorted in a manner that causes practitioners to miss important opportunities to grow and develop—not to mention help more clients.

e boundary between “belief in the process” and “denial of reality” is remarkably fuzzy. Hope is a significant contributor to outcome—accounting for as much as 30% of the variance in results. At the same time, it becomes toxic when actual outcomes are distorted in a manner that causes practitioners to miss important opportunities to grow and develop—not to mention help more clients.