It’s just two weeks ago. I was on a call with movers and shakers from a western state. They were looking to implement Feedback Informed Treatment (FIT)–that is, using measures of progress and the therapeutic relationship to monitor and improve the quality and outcome of mental health services.

It’s just two weeks ago. I was on a call with movers and shakers from a western state. They were looking to implement Feedback Informed Treatment (FIT)–that is, using measures of progress and the therapeutic relationship to monitor and improve the quality and outcome of mental health services.

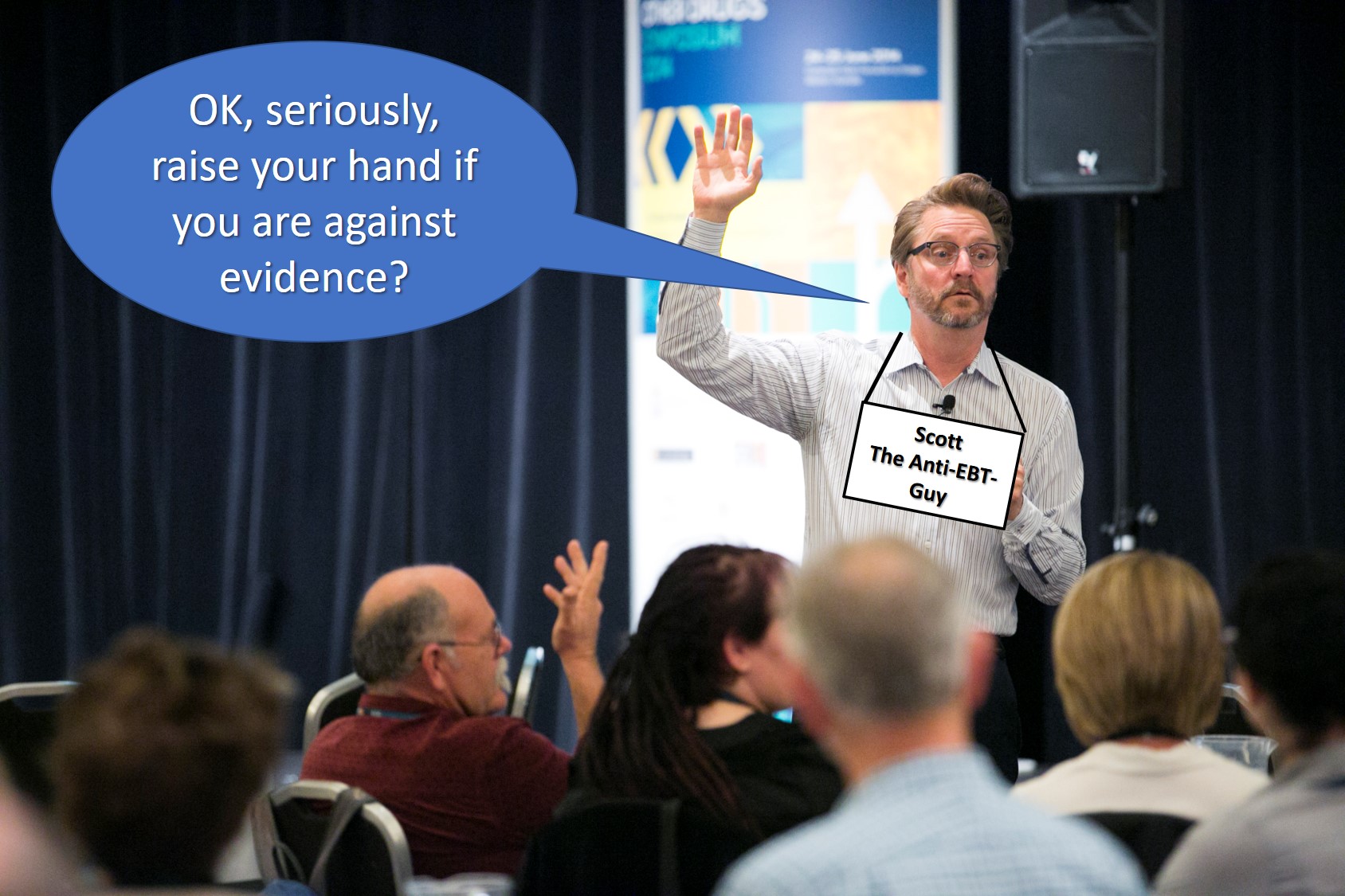

I was in the middle of reviewing the empirical evidence in support of FIT when one of the people on the call broke in. “I’m a little confused,” they said hesitantly, “I thought you were the anti-evidence-based practice guy.”

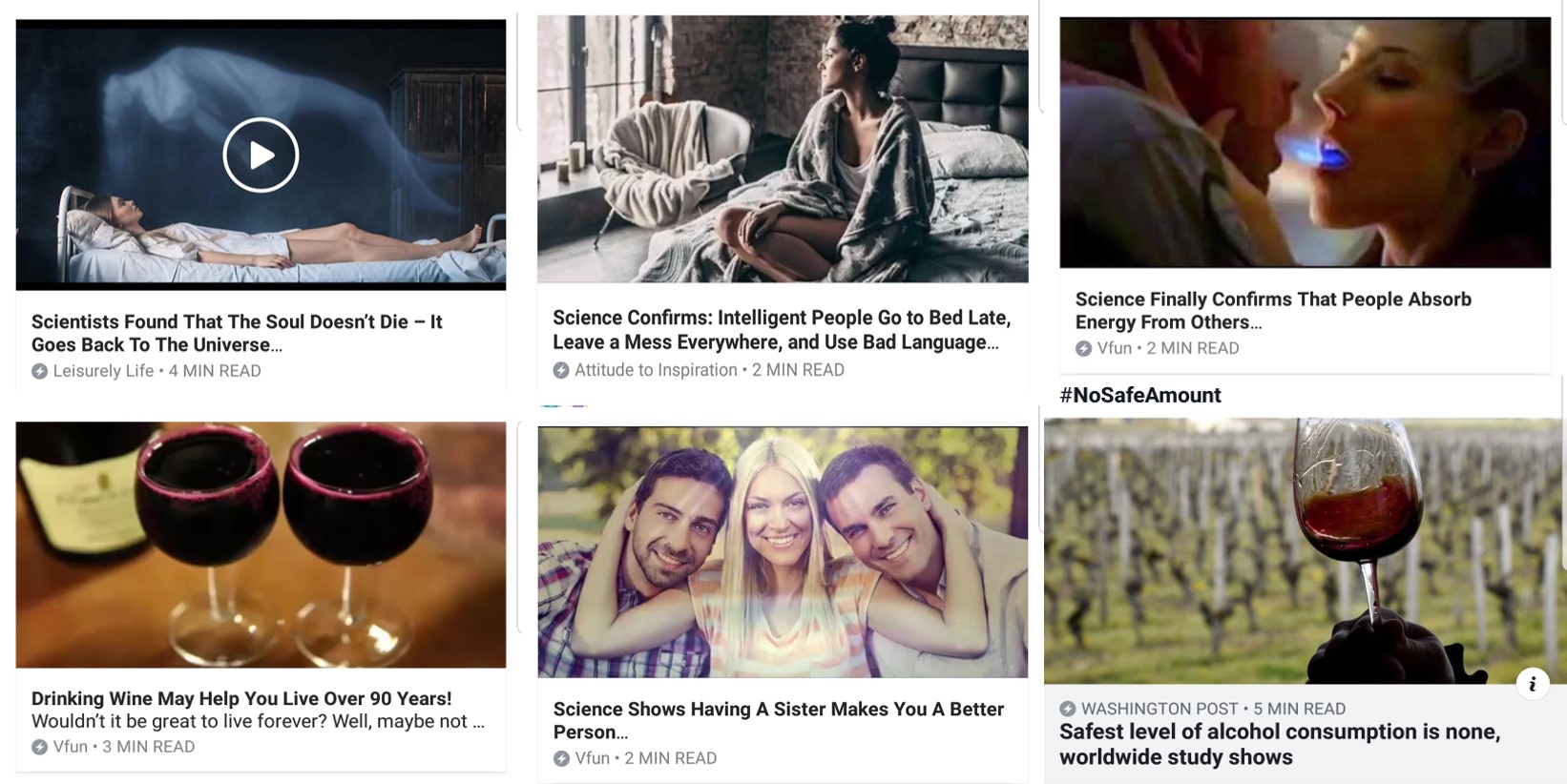

It’s not the first time I’ve been asked this question. In truth, it’s easy to understand why some might believe this about me. For more than two decades, I have been a vocal critic of the idea that certain treatments are more effective for some problems than others. Why? Because of the evidence! Indeed, one of the most robust findings over the last 40 years is that all approaches work equally well.

Many clinicians, and a host of developers of therapeutic approaches, mistakenly equate the use of a given model with evidence-based practice. Nothing could be further from the truth. Evidence-based practice is a verb not a noun.

According to American Psychological Association and the Institute of Medicine, there are three components: (1) using the best evidence; in combination with (2) individual clinical expertise; while ensuring the work is consistent with (3) patient values and expectations. “FIT,” I responded, “not only is consistent with, but operationalizes the definition of evidence-based practice, providing clinicians with reliable and valid tools for identifying when services need to be adjusted in order to improve the chances of achieving a successful outcome.”

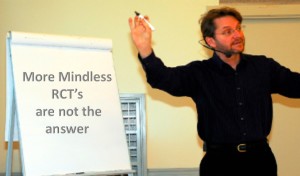

Here’s another recent question: “I’ve read somewhere that FIT doesn’t work.” When I inquired further, the asker indicated they’d been to a conference and heard about a study showing FIT doesn’t improve effectiveness (1). With the rising popularity of FIT around the world, I understand how someone might be rattled by such a claim. And yet, from the outset, I’ve always recommended caution.

In 2012, I wrote about findings reported in the first studies of the ORS and SRS, indicating they were simply, “too good to be true.” Around that same time, I also expressed my belief that therapists were not likely to learn from, nor become more effective as a result of measuring their results on an ongoing basis. Although later proven prophetic (1, 2), mine wasn’t a particularly brilliant observation. After all, who would expect using a stopwatch would make you a faster runner? Or a stethoscope would result in more effective heart surgeries? Silly, really.

What does the evidence indicate?

-

- The latest, most comprehensive meta-analysis of studies published in the prestigious, peer-reviewed journal, Psychotherapy Research, found that routine use of the ORS and SRS resulted in a small, yet significant impact on outcomes.

-

- Improving the outcome of care requires more than measurement. If FIT is to have any effect on engagement and progress in care, clinicians must be free of programmatic and structural barriers that restrict their ability to respond in real time to the feedback they receive. As obvious as it may seem, studies in which clinicians measure, but cannot change what they are doing in response show little or no effect (1).

-

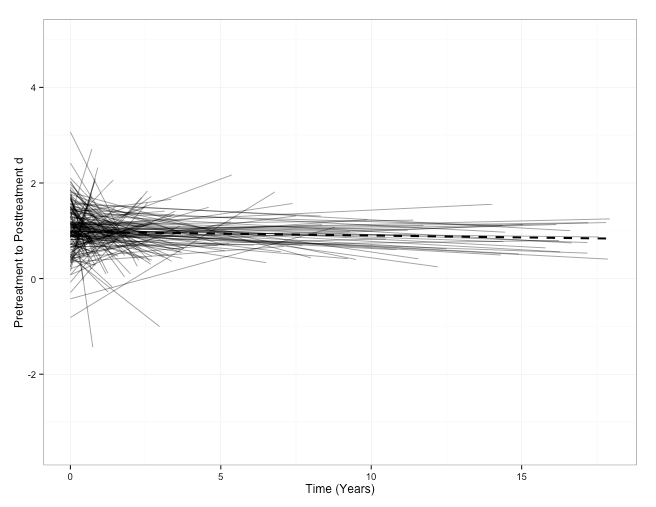

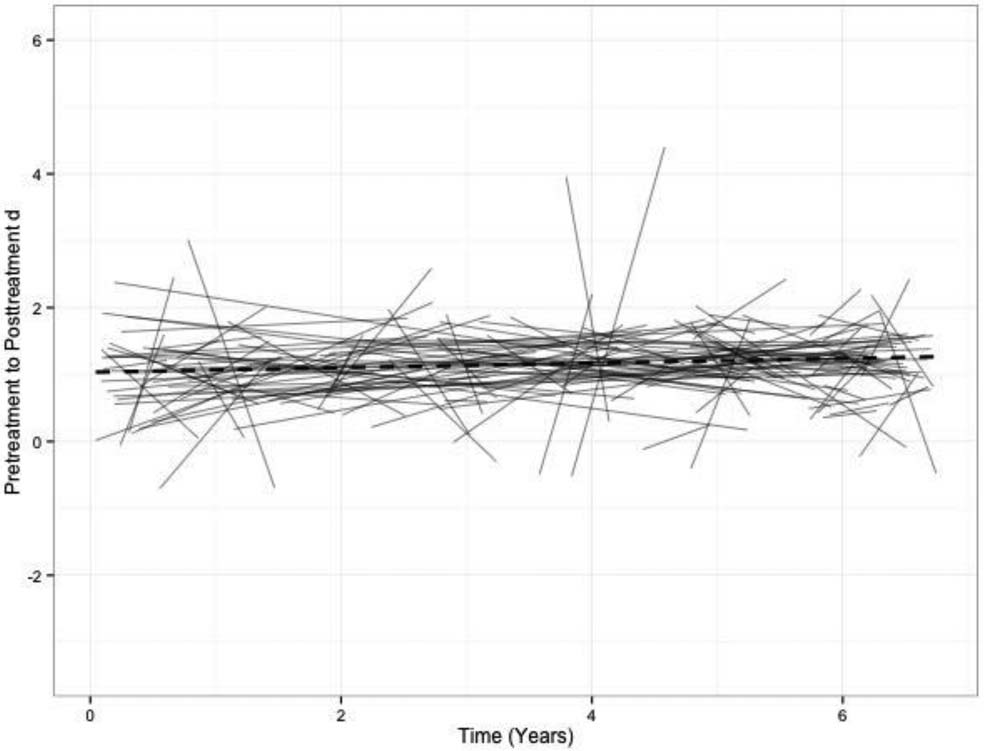

- With one exception, results reported in studies of FIT are confounded by the amount of training therapists receive, and the stage of implementation they (or the agency in which they work) are in, at the time the research is conducted. In many of the investigations published to date, participating therapists received 1 hour of training or less prior to beginning, and no supervision during, the study (1). Consistent with findings from the field of implementation science documenting that productive use of new clinical practices takes from three to five years, a new study conducted in Scandinavia found the impact of FIT grew over time, with few results seen in the first and second year of use. By year four, however, patients were 2.5 times more likely to improve when their therapists used FIT. In short, it takes time to learn how to do FIT, and for organizations to make the structural changes required for the development and maintenance of a feedback culture.

-

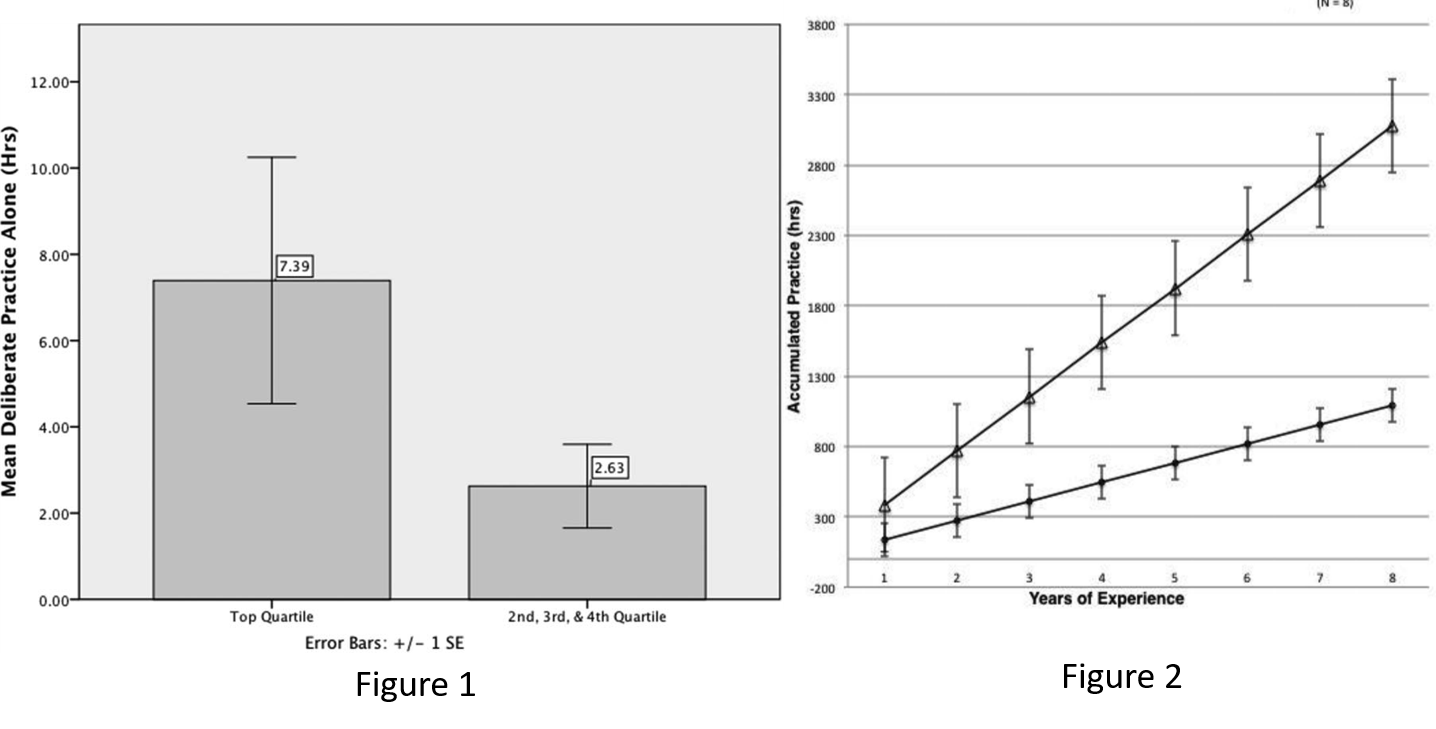

- Improving individual therapist effectiveness requires deliberate practice. It turns out,the best therapists devote twice as much time to the process. More, when employed purposefully and mindfully, the outcomes of average practitioners steadily rise at a rate consistent with performance improvements obtained by elite athletes (Click here if you want to watch an entertaining and informative video on the subject from the recent Achieving Clinical Excellence conference).

Before ending, let me mention one other question that comes up fairly often. “Why don’t you wear shoes when you present?” The picture to the left was taken at a workshop in Sweden last week and posted on Facebook! Over the years, I’ve heard many explanations: (1) it’s a Zen thing; (2) because I’m from California; (3) to make the audience feel comfortable; (3) to show off my colorful socks; and so on.

Before ending, let me mention one other question that comes up fairly often. “Why don’t you wear shoes when you present?” The picture to the left was taken at a workshop in Sweden last week and posted on Facebook! Over the years, I’ve heard many explanations: (1) it’s a Zen thing; (2) because I’m from California; (3) to make the audience feel comfortable; (3) to show off my colorful socks; and so on.

The truth, it turns out, is like the findings about FIT reported above, much more mundane. Care to guess?

(You can find my answer below)

P.S: Men’s shoes hurt my feet and back ache. I get neither when walking about in my stocking feet while standing and presenting all day.

It’s data taken from

It’s data taken from

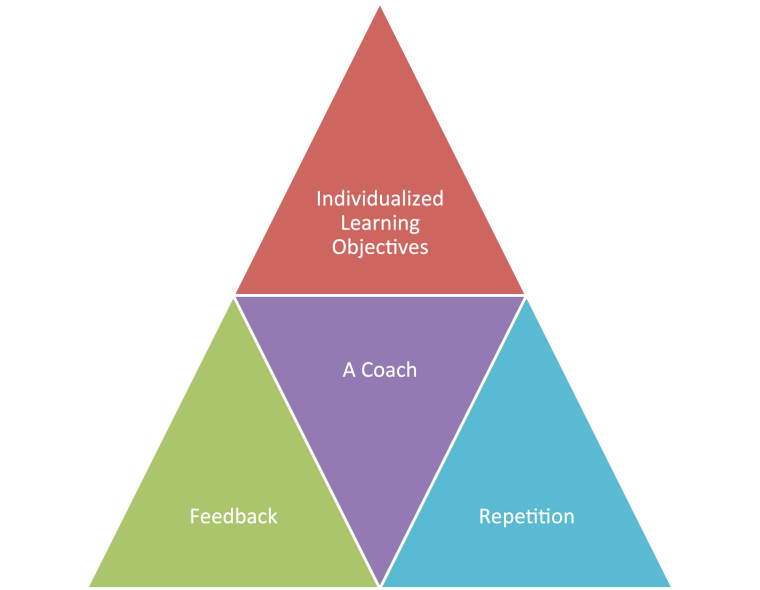

For the last several years, I’ve been advocating deliberate practice (DP)—conscious and purposeful effort aimed at improving specific aspects of an individual’s performance. DP contains four essential ingredients:

For the last several years, I’ve been advocating deliberate practice (DP)—conscious and purposeful effort aimed at improving specific aspects of an individual’s performance. DP contains four essential ingredients: