Ever see the film, Sliding Doors?

It’s an older movie with a familiar plot. Life can change in an instant — in this case, depending on whether or not lead character, Helen (played by Gwyneth Paltrow), catches a train. Both possibilities are explored, the results being dramatically different.

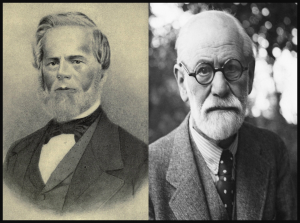

Now, consider the pictures to the left. Chances are you recognize one and not the other. Of course, one is strongly connected to the origins of psychotherapy, perhaps best considered the founder. He inspired a generation of followers, with several of his acolytes going on to achieve the same or even greater recognition and fame. The fundamental and revolutionary principle of his work? Many of the problems people struggle with are psychogenic in origin. Talking about them helped.

No, its not Freud. It’s the person on the left, Phineas Parkhurst Quimby.

Never heard of him? Sliding Doors.

By the time Freud was born, Quimby had been working for nearly two decades. His ideas and approach gave rise to the “New Thought” or “Mind Cure” movement in the United States, the philosophical and technical aspects of which arguably bear a much greater resemblance to the modern practice of psychotherapy than Freud’s. In sum, it emphasized the healing power of emotions, thoughts, and positive beliefs (1).

Unfortunately, the movement Quimby inspired occurred at roughly the same time American medical practitioners were professionalizing. Buoyed by a growing list of scientific discoveries, the group embraced the “somatic paradigm,” treating subjects of mind and emotion as relics of a bygone, unscientific era. In periodicals, professional journals, and the courts, they convincingly argued psychological suffering was the result of physical “lesions,” be they located in the brain, spine or elsewhere. Anyone believing otherwise was superstitious at best, potentially dangerous at worse.

The rest is, as is often said, history. It is interesting to imagine how mental health care might be different today had the medicophysical paradigm emerging in the final decades of the 19th century not so thoroughly vanquished a psychological point of view. Freud — who biographer, Frank Sulloway once famously labeled, “The biologist of the mind” — might well be a footnote in the story of the field. How might our understanding of and ability to help be different had we embraced the role of thinking, emotion, and trauma so central to contemporary treatment approaches, a century ago?

Then again, what if, in reality, we’re all still standing on the platform waiting for our train to arrive? After all, much of what occupied professional attention then, continues to dominate now. For example, the field acts as though our methods are specifically remedial to the problems our clients bring to care. Thus, CBT is said to cure by targeting the dysfunctional thoughts that cause depression while brain-based approaches rewire the “neural foundations of various disorders and lead[ing] to specific psychotherapeutic conclusions” (2). Common wisdom holds the most enlightened perspective is some kind of hybrid — the biopsychosocial model. All clear representations of the medical model. All which enjoy no empirical support. All which may be implicated in the lack of improvement in the outcome of psychotherapy over the last four decades (it’s likely longer, but valid and reliable studies of effectiveness only started appearing in the late 1950’s [3, 4, 5]).

Then again, what if, in reality, we’re all still standing on the platform waiting for our train to arrive? After all, much of what occupied professional attention then, continues to dominate now. For example, the field acts as though our methods are specifically remedial to the problems our clients bring to care. Thus, CBT is said to cure by targeting the dysfunctional thoughts that cause depression while brain-based approaches rewire the “neural foundations of various disorders and lead[ing] to specific psychotherapeutic conclusions” (2). Common wisdom holds the most enlightened perspective is some kind of hybrid — the biopsychosocial model. All clear representations of the medical model. All which enjoy no empirical support. All which may be implicated in the lack of improvement in the outcome of psychotherapy over the last four decades (it’s likely longer, but valid and reliable studies of effectiveness only started appearing in the late 1950’s [3, 4, 5]).

What, you might ask, is the alternative? That’s exactly what Dan Lewis, M.D. and I discuss on the latest installment of the Book Case. All Aboard!

PLEASE, let me know your thoughts …

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Leave a Reply