I’ve just returned from a week in Denmark providing training for two important groups. On Wednesday and Thursday, I worked with close to 100 mental health professionals presenting the latest information on “What Works” in Therapy at the Kulturkuset in downtown Copenhagen. On Friday, I worked with a small group of select clinicians working on implementing feedback-informed treatment (FIT) in agencies around Denmark. The day was organized by Toftemosegaard and held at the beautiful and comfortable Imperial Hotel.

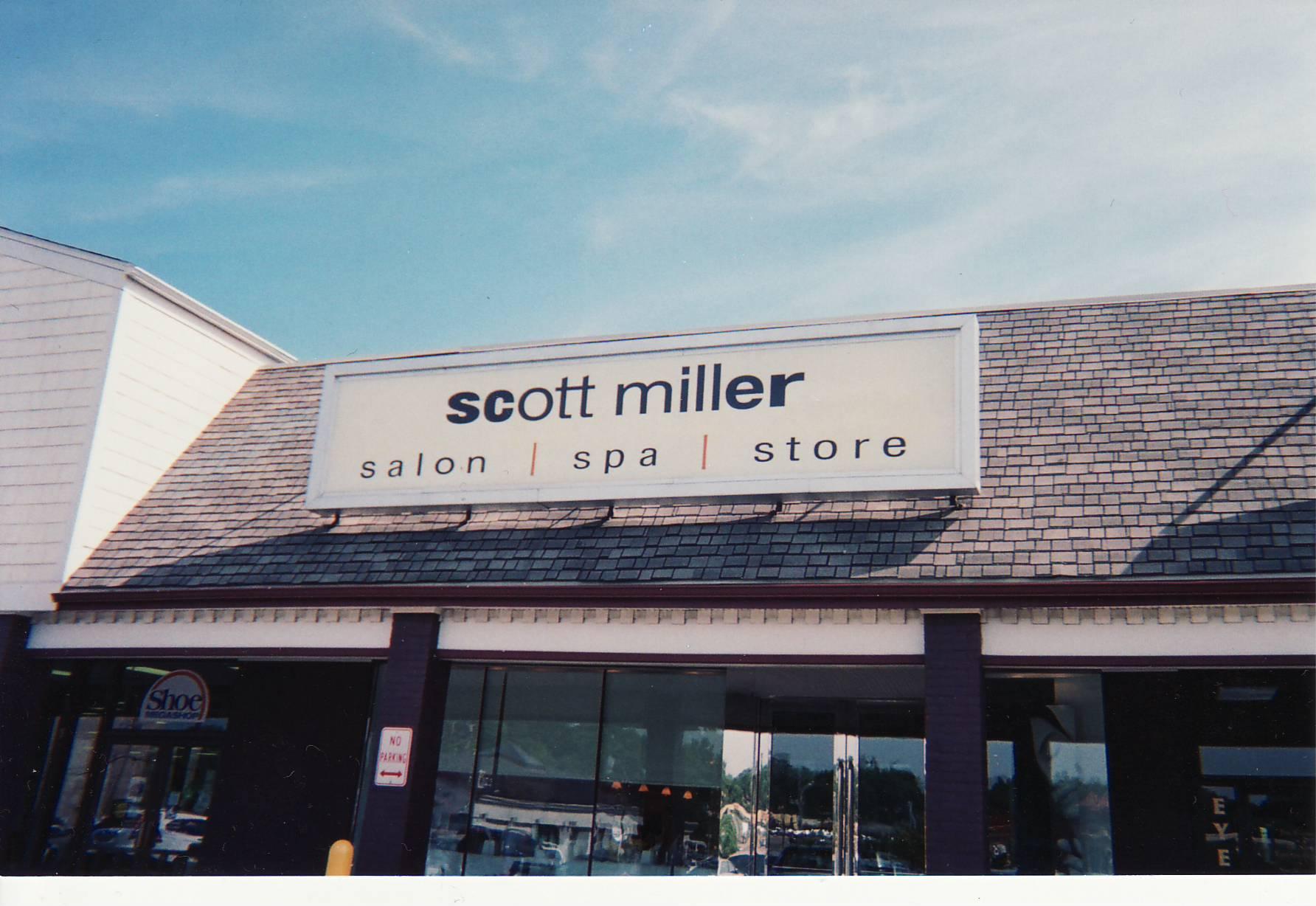

In any event, while I was away, I received a letter from my colleague and friend, M. Duncan Stanton. For many years, “Duke,” as he’s known, has been sending me press clippings and articles both helping me stay “up to date” and, on occasion, giving me a good laugh. Enclosed in the envelope was the picture posted above, along with a post-it note asking me, “Are you going into a new business?!”

As readers of my blog know, while I’m not going into the hair-styling and spa business, there’s a grain of truth in Duke’s question. My work is indeed evolving. For most of the last decade, my writing, research, and training focused on factors common to all therapeutic approaches. The logic guiding these efforts was simple and straightforward. The proven effectiveness of psychotherapy, combined with the failure to find differences between competing approaches, meant that elements shared by all approaches accounted for the success of therapy (e.g., the therapeutic alliance, placebo/hope/expectancy, structure and techniques, extratherapeutic factors). As first spelled out in Escape from Babel: Toward a Unifying Language for Psychotherapy Practice, the idea was that effectiveness could be enhanced by practitioners purposefully working to enhance the contribution of these pantheoretical ingredients. Ultimately though, I realized the ideas my colleagues and I were proposing came dangerously close to a new model of therapy. More importantly, there was (and is) no evidence that teaching clinicians a “common factors” perspective led to improved outcomes–which, by the way, had been my goal from the outset.

The measurable improvements in outcome and retention–following my introduction of the Outcome and Session Rating Scales to the work being done by me and my colleagues at the Institute for the Study of Therapeutic Change–provided the first clues to the coming evolution. Something happened when formal feedback from consumers was provided to clinicians on an ongoing basis–something beyond either the common or specific factors–a process I believed held the potential for clarifying how therapists could improve their clinical knowledge and skills. As I began exploring, I discovered an entire literature of which I’d previously been unaware; that is, the extensive research on experts and expert performance. I wrote about our preliminary thoughts and findings together with my colleagues Mark Hubble and Barry Duncan in an article entitled, “Supershrinks” that appeared in the Psychotherapy Networker.

Since then, I’ve been fortunate to be joined by an internationally renowned group of researchers, educators, and clinicians, in the formation of the International Center for Clinical Excellence (ICCE). Briefly, the ICCE is a web-based community where participants can connect, learn from, and share with each other. It has been specifically designed using the latest web 2.0 technology to help behavioral health practitioners reach their personal best. If you haven’t already done so, please visit the website at www.iccexcellence.com to register to become a member (its free and you’ll be notified the minute the entire site is live)!

As I’ve said before, I am very excited by this opportunity to interact with behavioral health professionals all over the world in this way. Stay tuned, after months of hard work and testing by the dedicated trainers, associates, and “top performers” of ICCE, the site is nearly ready to launch.

Leave a Reply