Psychology has been in the headlines a fair bit of late—and the news is not positive. I blogged about this last year, when a study appeared documenting that the effectiveness of CBT was declining–50% over the last four decades.

Psychology has been in the headlines a fair bit of late—and the news is not positive. I blogged about this last year, when a study appeared documenting that the effectiveness of CBT was declining–50% over the last four decades.

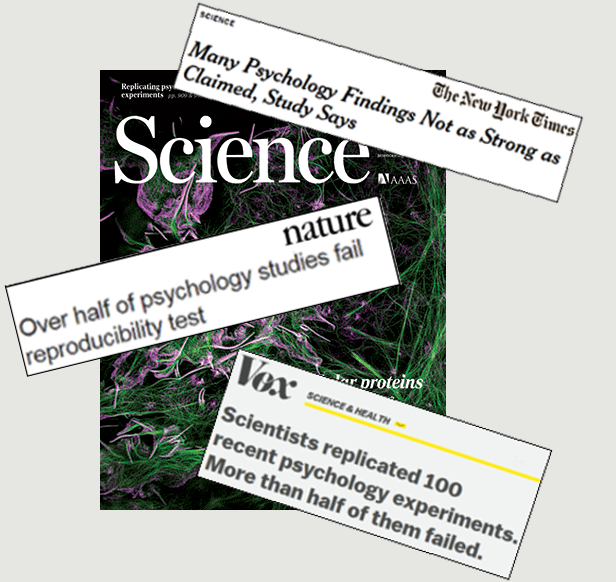

The problem is serious. Between 2012 and 2014, for example, a team of researchers working together on their free time tried to replicate 100 published psychology experiments and succeeded only a third of the time! As one might expect, such findings sent shock waves through academia.

Now, this week, The British Psychological Society’s Research Digest piled on, reviewing 10 “famous” findings that researchers have been unable to replicate—despite the popularity and common sense appeal of each. Among others, these include:

- Power posing does not make you more powerful;

- Smiling does not make you happier;

- Exposing you to words (known as “priming”) related to ageing does not cause you to walk like an old person;

- Having a mental image of a college professor in mind does not make you perform more intelligently (another priming study);

- Being primed to think of money will not cause make you act more selfishly; and

- Despite being reported in nearly every basic psychology text, babies are not born with the power to imitate.

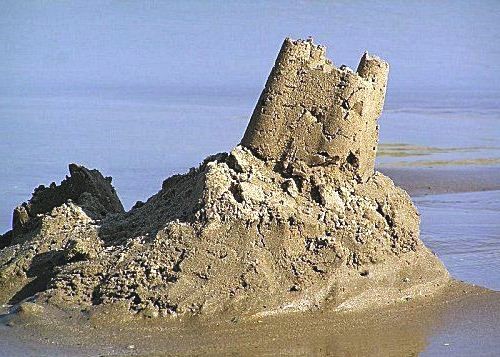

Clearly, replication is a problem.  The bottom line? Much of psychology’s evidence-base is built on a foundation of sand.

The bottom line? Much of psychology’s evidence-base is built on a foundation of sand.

Amidst all the controversy, I couldn’t help thinking of psychotherapy. In this area, I believe, the problem with the available research is not so much the failure to replicate, but rather an unwillingness to accept what has been replicated repeatedly. Contrary to hope and popular belief, one—if not the most—replicated finding is the lack of difference in outcome between psychotherapeutic approaches.

It’s not for lack of trying. Massive amounts of time and resources have been spent comparing treatment methods. With few exceptions, either no or inconsequential differences are found.

Consider, for example, the U.S. Government spent  $33,000,000 studying different approaches for problem drinking only to find what we already know: all worked equally well. A decade later, the British officials spent millions of pounds on the same subject with similar results.

$33,000,000 studying different approaches for problem drinking only to find what we already know: all worked equally well. A decade later, the British officials spent millions of pounds on the same subject with similar results.

Just this week, a study was released comparing the hugely popular method called DBT to usual care in the treatment of “high risk suicidal veterans.” Need I tell you what they found?

As the Ground-Hog-Day-like quest continues, another often replicated finding is ignored. One of the best predictors of the outcome of psychotherapy is the quality of the therapeutic relationship between the provider and recipient of care. That was one of the chief findings, for example, in both of the studies on alcohol treatment cited above (1, 2). Put simply, better relationship = improved engagement and effectiveness.

Sadly, but not surprisingly, research, writing, and educational opportunities focused on the alliance lags model and techniques. Consider this: slightly more than 55,000 books are in print on the latter subject, compared to a paltry 193 on the former. It’s mind-boggling, really. How could one of the most robust and replicated findings in psychotherapy be so widely ignored?

My colleague Daryl Chow is working hard to get beyond the “lip service” frequently paid to the therapeutic relationship. At the ICCE Professional Development training this last August, he presented findings from an ongoing series of studies aimed at helping clinicians improve their ability to engage, retain, and help people in psychotherapy by targeting training to the individual practitioners strengths and weaknesses. Not surprisingly, the results show slow and steady improvement in connecting with a broader, more diverse, and challenging group of clinical scenarios! Those in attendance learned how to build these skills into an individualized, professional development plan.

Trust me when I say, we won’t be ignoring this and other robust findings related to improving effectiveness at the upcoming ICCE intensive trainings in Chicago. Registration is open for both the Advanced and Supervision Intensives. Join us and colleagues from around the world.

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Hi Scott, Thanks for sharing. Regarding the SMILING technique, I found it helped when I practiced it. However, the experience and outcomes of any interventions are always very subjective. What works for one person, does not always work for another, in most therapy techniques indicating problems with reliability – as your studies have found. I can give the same strategies to clients experiencing similar concerns and what will work for one will not work for another and vice versa. I find it difficult to provide strategies to clients if I have found them unhelpful to use myself. I trial strategies myself and if they work, I share them with clients. I agree with your comment too about the predictability of success in therapy is based on the therapeutic relationship. It’s paramount to build and sustain rapport to achieve positive outcomes. http://www.jacquelinehogan.com

What about research on comparing treatment methods with children and adolescents (specially children)?

Do you have information on that?

Thank you!

Thanks Scott for this article……. no one else has been game to say this…. the CBT Church is a strong and prolific congregation…… I wonder where the next trend to engulf psychology, mindfulness, will end up as well …. we need to be clear about the strengths, weaknesses and purpose of all methods of human engagement…

So what is it about the therapeutic relationship? Mainstream research has yet to answer that question. My answer (see my articles in PsycINFO) is the therapist offering sufficient support for what the client is experiencing so that that person’s subsequent heightened emotional experiencing arises in an unforced way; i.e., coincident with that support. Therapists who follow a manualized approach do not support the client’s experiencing. In fact, such an attitude actually distracts clients from their experiencing. So what happens when a client’s emotional experiencing arises in an unforced way? That person will quite likely tear/cry and/or sound indignant, which term is preferred over “anger” as it is a healing response to unfair/unjust treatment. It’s what I call therapeutic catharsis, and which, if you persist in supporting a client’s experiencing – and especially when you don’t understand why the client is talking about what she/he’s talking about – you will see that it is healing and not retraumatizing. The FORCED activation of emotional experiencing is retraumatizing. That happens when an unexpected stimulus triggers a flight or fight reaction; i.e., too much unresolved experience is kicked up out of sequence. Many articles on psychotherapy have examples of therapeutic crying. However, I’ve yet to see any mention of it in the Summary as the reason for that particular client’s profound change.

Jeffrey, I’m with you, observing, like you, the importance of experience that can emerge from the quality of relationship. Being CBT trained, I went through many phases in 20 years of practice from being strict and sticking to a plan to be being very process oriented and leading from one step behind.

In Australia, given the max 10 sessions per calendar year and a high level of involvement of GPs, I often feel the pressure of manufacturing “outcomes”, from GPs and therefore from clients alike, and that has all sorts of implications hindering us the work to do that could be done, if circumstances were more favourable.

Having had tend years of training with various trainers, and having practiced for decades, I’ve always suspected it was the actual relationship and not the particular school that was the key

Great post Scott. The replications issue is becoming a big challenge in research world, pushing us back to rigour and good methods. So thanks for pointing this up. The problem with alliance focus as opposed to technique focus is that this is a self-regarding cycle. We can possibly assume that alliance is a requisite for effective therapy (there of course is a problem with the large number of studies). We can identify where alliance fails and why. What then? Once we start to intervene to improve alliance we are back to technique. Thanks again for the work.

Unfortunately these studies which cannot be replicated have formed the evidence base for funding….so when will someone wake up to consider it?!?!