Later today, I board United flight 908 on my way to workshops scheduled in Holland and Belgium. My routine in the days leading up to an international trip is always the same. I slowly gather together the items I’ll need while away: computer (check); european electric adapter (check); presentation materials (check); clothes (check). And, oh yeah, two decks of playing cards and close up performance mat.

That’s me (pictured above) practicing a “ribbon spread” in my hotel room following a day of training in Marion, Ohio. It’s a basic skill in magic and I’ve been working hard on this (and other moves using cards) since last summer. Along the way, I’ve felt both hopeful and discouraged. But I’ve kept on nonetheless taking heart from what I’m reading about skill acquisition.

Research on expertise indicates that the best performers (in chess, medicine, music, sports, etc.) practice every day of the week (including weekends) for up to four hours a day. Sounds tiring for sure. And yet, the same body of evidence shows that world class performers are able to sustain such high levels of practice because they view the acquisition of expertise as a long-term process. Indeed, in a study of children, researcher Gary McPherson found that the answer to a simple question determined the musical ability of kids a year later: “how long do you think you’ll play your instrument?” The factors that were shown to be irrelevant to performance level were: initial musical ability, IQ, aural sensitivity, math skills, sense of rhythm, income level, and sensorimotor skills.

The type of practice also matters. When researchers Kitsantas and Zimmerman studied the skill acquisition of experts, they found that 90% of the variation in ability could be accounted for by how the performers described their practice; the types of goals they set, how they planned and executed strategies, self-monitored, and adapted their performance in response to feedback.

So, I take my playing cards and close-up mat with me on all of my trips (both domestic and international). I don’t practice on planes. Gave that up after getting some strange stares from fellow passengers as they watched me repeat, in obsessive fashion, the same small segment of my performance over, and over, and over again. It only made matters worse if they found out I was a psychologist. I’d get that “knowing look,” that seemed to say, “Oh yeah.” Anyway, I also managed to lose a fair number of cards when the deck–because of my inept handling while trying to master some particular move–went flying all over the cabin (You can imagine why I’ve been less successful in keeping last year’s New Year resolution to learn to play the ukelele).

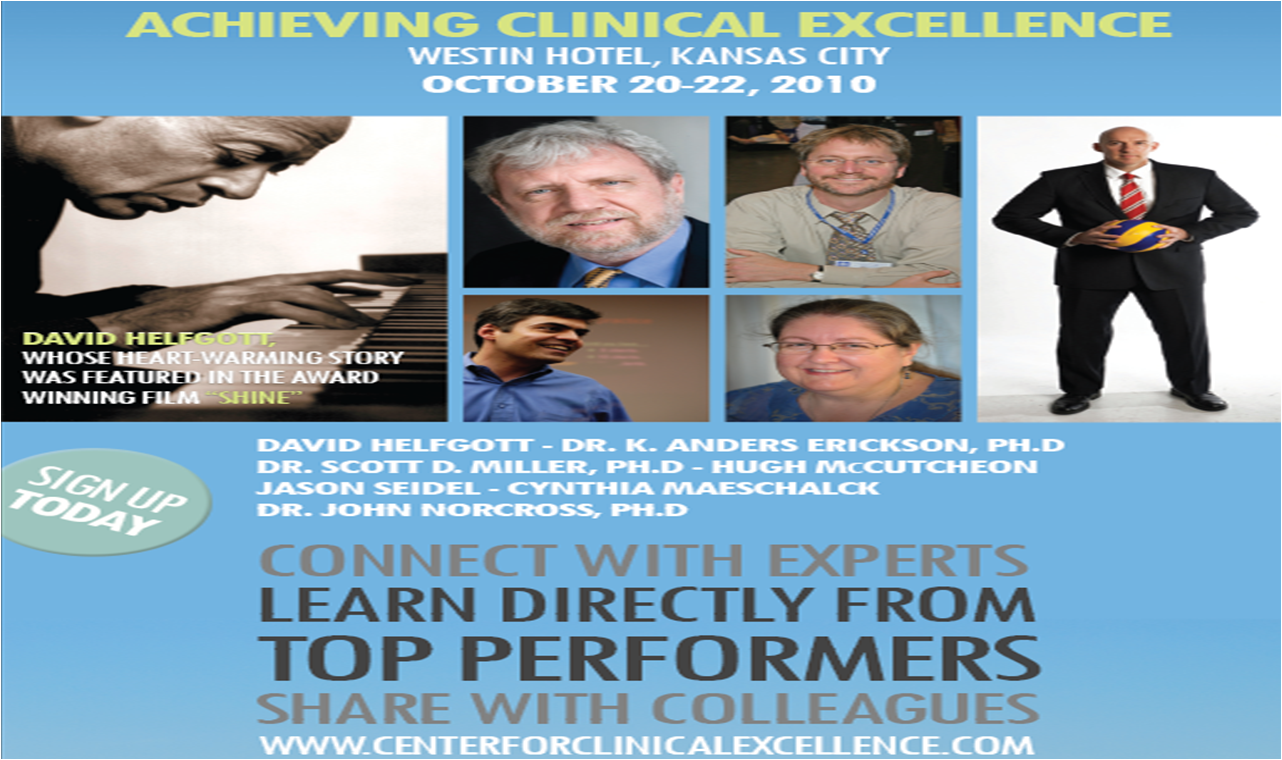

Once I’m comfortably situated in my room, the mat and cards come out and I work, practice a specific handling for up to 30 minutes followed by a 15-20 minute break. Believe it or not, learning–or perhaps better said, attempting to learn–magic has really been helpful in understanding the acquisition of expertise in my chosen field: psychology and psychotherapy. Together with my colleagues, we are translating our experience and the latest research on expertise into steps for improving the performance and outcome of behavioral health services. This is, in fact, the focus of the newest workshop I’m teaching, “Achieving Clinical Excellence.” It’s also the organizing theme of the ICCE Achieving Clinical Excellence conference that will be held in Kansas City, Kansas in October 2010. Click on the photo below for more information.

In the meantime, check out the two videos I’ve uploaded to ICCETV featuring two fun magic effects. And yes, of course, feedback is always appreciated!