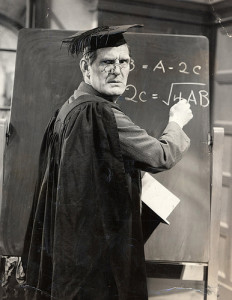

Mr. Gomm was my sixth grade teacher. Tall and angular, with a booming voice and stern demeanor, he remains a forbidding figure from my childhood.

Mr. Gomm was my sixth grade teacher. Tall and angular, with a booming voice and stern demeanor, he remains a forbidding figure from my childhood.

I’ll never forget the day he slammed his open hand on my desk, bellowing “That, Mr. Miller, is an assumption!” Turning abruptly, he walked to the chalkboard, and began writing, one capital letter at a time: A, S, S, U, M, E.

“And do you know what happens when we assume, Mr. Miller?” he asked.

“Speak up!” I remember him commanding. But I just sat there, like a deer in the headlights.

I’m sure you know what happened next. Returning to the board, he quickly drew slash marks between the S and U, and U and M: ASS/U/ME.

For emphasis, he then tapped each section loudly with his chalk as he spoke, “Let me spell it out for you, Mr. Miller. To assume is to make an ass out of you and me!”

It’s a moment I recall with absolute clarity. Only later — much later — did I come to realize I’d not understood the point he’d  been trying to make at the time. Indeed, at recess, all anyone could talk about was that Mr. Gomm said the word “ass” out loud in class. Soon, we were applying our new knowledge to anything anyone did on the playground that we didn’t like: butting in line, missing a critical shot in kick ball, or any of the other possible social faux pas among marginally pubescent adolescents.

been trying to make at the time. Indeed, at recess, all anyone could talk about was that Mr. Gomm said the word “ass” out loud in class. Soon, we were applying our new knowledge to anything anyone did on the playground that we didn’t like: butting in line, missing a critical shot in kick ball, or any of the other possible social faux pas among marginally pubescent adolescents.

“You just made an ass out of you and me!” we repeated with glee at the slightest provocation.

Beyond the obvious irony involved, it turns out tr. Gomm was only half right. Yes, assuming — supposing without proof — is fraught with risk. That said, presuming — taking something for granted based on probability — is, as the incident so clearly demonstrates, just as problematic. In his mind, he’d made a sensible presumption: we would get “it.” After all, he knew us. We were his students. We made the same mistake. Based on our experience of him, we figured he was teaching us another valuable lesson, and then assumed we’d understood what he’d said.

Prior to last week, I’d not thought of Mr. Gomm for ages. I was was reminded of him after puzzling over a slew of questions about feedback-informed treatment (FIT) posted on our online discussion forums at the International Center for Clinical Excellence. On the surface, all appeared to be straightforward requests for information, requiring nothing more than a simple and direct response. The trouble was that any answer one might give ended up confirming assumptions contained in the queries that were fundamentally untrue or inaccurate.

While the particulars varied, a theme shared by many of the posts was whether one could or should trust scores on the Outcome and Session Rating Scales (ORS & SRS) with certain clients — in particular, people who were shy, mandated into treatment, cognitively compromised, or emotionally disturbed.

To be sure, it’s not the first time I’d encountered such concerns. Indeed, they frequently come up at the beginning of introductory workshops on FIT:

To be sure, it’s not the first time I’d encountered such concerns. Indeed, they frequently come up at the beginning of introductory workshops on FIT:

“Court ordered clients won’t be truthful.”

“The feedback from client’s with (borderline personality disorder, bipolar, psychosis) won’t be reliable or valid.”

“People from this (age group, culture) are not (accustomed to or incapable of) providing feedback to professionals.”

When I have several hours to teach, interact, and illustrate, I usually ask people to wait with such observations, promising an answer will emerge in time. In the truncated, two-dimensional space of most social media interactions, however, I’ve found a similar evolution of understanding much more challenging. Hence this post.

Of course, in the best of all worlds, people would get more training. Answers are available. Given the simplicity of the scales — you can learn to administer and score the ORS and SRS in less than a minute — the temptation to dive in, presuming our existing clinical knowledge and experience applies to their use, is simply too great for most to resist. Consider this: several hundred thousand practitioners have download the measures from my website in just the last couple of years! Of these, fewer than 2 or 3% have had any training! In the end, the unquestioned assumptions brought to the process cause most to get stuck and eventually give up.

So, what about the concerns noted above?

All make perfect sense IF the ORS and SRS are thought of as assessments, the helpfulness of which depend on the accuracy of the data collected. By contrast, were the measures primarily seen as tools to help engage clients, an entirely different set of assumptions becomes possible. For example, rather than interpreting high ORS scores of a court-ordered client as evidence of dishonesty or denial that must be confronted or overcome, they could be treated as an opportunity to connect with, explore, and understand their experience and world view.

In practical terms that means taking client scores at face value. Leaving traditional assumptions aside, the clinician would first acknowledge and then respond logically to what is reported on the scale. “I see from your responses, you are doing quite well,” continuing, “So, why did you decide to come see me today?” Should the client say, as most readily do, they were sent by the courts (or employer, parents, or partner), the clinician responds by asking them to complete the measure as if they were the person who sent them. After all, from their perspective, that’s why they are there! The discussion can then turn to closing the gap between the client’s and referral source’s scores, beginning, for instance, with asking, “What have they missed about you that, once recognized, will lead them to score you higher?” Along the way, the result of this line of inquiry is greater participation of the client in treatment — the factor long ago established as the number one process-related predictor of outcome (see Orlinsky, Grawe, & Parks, 1994).

And what about the other questions?

As already stated, answers are available — ones that leave most thinking, “Duh, why didn’t I think of that?” To be blunt, we can’t so long as we are unaware we are thinking something else! That’s where a more in-depth training in FIT can prove helpful. Join colleagues from around the world and our international faculty this coming Spring in Chicago for the three-day, Advanced FIT Intensive. We’ll not only challenge your thinking, we’ll provide a thorough grounding in the principles and skills of using feedback to inform and improve the quality of mental health and substance abuse services with a broad and diverse clinical population — training which, research shows, improves therapist effectiveness. Registration is limited to 40 participants. Click either of the icons below for more information.

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

Thanks Scott for this entry! Very helpful points for whenever i do outreach and talk to clinicians who have similar concerns. Hope you’re well!

Use of the scales is an intervention which provides an experience of empowerment and equality in relationship. And don’t many client problems have their origins in experiences with qualities exactly opposed to those?

Is it possible to participate in the Intensive online

I did the three day workshop in Melbourne (2019), taking my Practice Manager with me. Together we have slowly implemented FIT both therapeutically and administratively as part of our reporting over this past year. The practice is just reaching its quota to gather good data. It has been a slow and searching journey for us. I can only say that those who do not drift back and forward through the manuals, or undertake training are denying themselves the fullness of FIT. A year in I am glad to say I am a babe in the woods. It is exciting and filled with opportunity. It is changing my practice. Clients are warming to it and taking greater ownership of the space between us. We work creatively together on what matters to them for improving their wellbeing. What I’m wondering is where the three day Australian training places me in terms of going to Chicago for more training? Or are you coming back with extra training for us in Australia? I want another year’s data before I go to Chicago or my next raining I’m thinking.

I make use of my ORS & SRS inquiries to very simply demonstrate “I want to know more about how and who you are because I care this much about you and our journey together”” … and to do this without being attached to the outcome.