Over the last 10 days or so, I’ve been digesting a recently published article on the therapeutic alliance — reading, highlighting, tracking down references, rereading, and then discussing the reported findings with colleagues and a peer group of fellow researchers. It’s what I do.

Over the last 10 days or so, I’ve been digesting a recently published article on the therapeutic alliance — reading, highlighting, tracking down references, rereading, and then discussing the reported findings with colleagues and a peer group of fellow researchers. It’s what I do.

The particular study has been on my “to be read” pile for the better part of a year, maybe more. Provocatively titled, “Is the Alliance Really Therapeutic?” it promises to answer the question in light of “recent methodological advances.”

I know this will sound strange — at least at first — but throughout, I kept finding myself thinking of the assasination of the 35th President of the United States, John F. Kennedy. Bear with me as I explain.

I personally remember the shock and grief of this event. Although I was only six years old at the time, I have vivid memories, watching televised segments of the funeral procession down Pennsylvania Avenue under a grey, overcast and rainy sky. “Why?” my family and the Nation asked, and “How?”

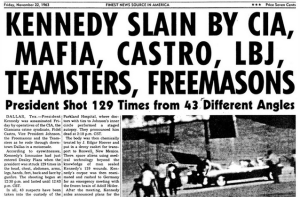

You likely know the rest of the story.  Within hours, a suspect was arrested. Two days later, he was murdered on live TV by a Dallas nightclub owner. Ever since, events surrounding the assasination have been the subject of heated debate. More than 2,000 books have been published, each offering a different theory of the event — a veritable “Who’s who” of suspects, including but not limited to the Soviet Union, CIA, Mafia, Cuban government, and Vice President of the United States.

Within hours, a suspect was arrested. Two days later, he was murdered on live TV by a Dallas nightclub owner. Ever since, events surrounding the assasination have been the subject of heated debate. More than 2,000 books have been published, each offering a different theory of the event — a veritable “Who’s who” of suspects, including but not limited to the Soviet Union, CIA, Mafia, Cuban government, and Vice President of the United States.

Whatever you might believe, it’s hard to fault the majority of Americans — 61% in the most recent polls — who seriously doubt that the slight, unemployed, thrice court-martialed former marine, acted alone. To many, in fact, it’s simply inconceivable. And, that’s the point. As investigative reporter, Gerald Posner, observed in his book Case Closed, “The notion that a misguided sociopath … wreaked such havoc [makes] the crime seem senseless” (p. xviii). By contrast, concluding there was an elaborate plot involving important and powerful people, embues Kennedy’s death with meaning equal to his stature and significance in the mind of the public.

Said another way, maybe, just maybe, in our attempts to reconcile the facts with our feelings, we made a molehill into a mountain … which brings me back to the article about the therapeutic relationship. The empirical evidence is clear: the quality of the alliance between client and clinician is one of the most potent and reliable predictors of successful psychotherapy.

Said another way, maybe, just maybe, in our attempts to reconcile the facts with our feelings, we made a molehill into a mountain … which brings me back to the article about the therapeutic relationship. The empirical evidence is clear: the quality of the alliance between client and clinician is one of the most potent and reliable predictors of successful psychotherapy.

According to the most recent and thorough review of the empirical literature:

- Better alliances result in better outcomes when working with individuals, groups, couples and families, children and adolescents, and mandated/involuntary clients;

- With regard to specific qualities, better outcomes result the more therapists:

- Like, value, and care for the client (known as the “real” relationship, it contributes more to outcome than relational elements associated with the doing of therapy. Effect Size [E.S.] ~ .80 );

- Communicate their understanding of and compassion for the client (E.S. ~ .58);

- Collaborate with the client regarding the focus (e.g., problem) and goals for treatment (E.S. ~ .49);

- Present as accessible, approachable, and sincere (i.e., congruent and genuine, E.S. ~ .46)

- Demonstrate respect, warmth, and positive regard (E.S. ~ .36);

- Seek and utilize formal feedback regarding the client’s experience of progress and the therapeutic alliance (E.S. ~ .33 – .49);

- Express emotions and generate hope and expectancy of positive results (E.S. = .56 & .36, respectively).

Sounds pretty straightforward and simple to me. In a relatively efficient fashion (worldwide the average number of visits is around 5 visits), we establish relationships with people that result in significant improvements in their well being. With regard to the latter, as reviewed many times on my blog, the average recipient of psychotherapy is better off than 80% of those with similar problems that do not.

Sounds pretty straightforward and simple to me. In a relatively efficient fashion (worldwide the average number of visits is around 5 visits), we establish relationships with people that result in significant improvements in their well being. With regard to the latter, as reviewed many times on my blog, the average recipient of psychotherapy is better off than 80% of those with similar problems that do not.

That said, is the relationship we offer people so astounding that it forever changes them? Judging by the article’s dense language and near inpenetrable statistical procedures, you’d assume so. Yet ultimately, it fails to show as much, focusing instead on defining characteristics and qualities of clients amenable to a particular theoretical orientation rather than the relationship.

Now, before you object, please note, I did not say relationships — in life or in therapy — were easy. But therein lies the risk. Challenging or difficult (e.g., a lone gunman taking out a beloved and powerful figure) is equated with complicated (i.e., must have been a conspiracy). Add to that the tendency of professionals to embue their interactions with clients with life-changing significance and voila! we are poised, as a field, to make mountains out of molehills. Nowhere is this more easy to see than in the language we use to describe our work. We “treat,” have “countertransference reactions,” “repair ruptures,” and form “therapeutic alliances” rather than connect, experience frustration (or other feelings), and develop relationships.

It’s time to embrace what 50 years of evidence plainly shows: yes, we offer an important service, an opportunity for someone to feel understood, get support while going through a difficult period, solve problems, learn new and different ways for approaching life’s challenges, and every once in a while –maybe one in a hundred — something more. To do that, what’s needed is humility and a relentless focus on the fundamentals. Given the history of our field, that alone will prove hard enough.

Embracing the evidence and focusing on fundamentals is precisely what we’ll be doing, by the way, at the Deliberate Practice Intensive this summer coming August in Chicago. Join colleagues from around the world to learn how to use this simple (not easy) way for improving your effectiveness! For more info, click here or on the banner below.

Until next time,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

With increased practice experience and the sharpening of one’s intuitive sense, a therapist will/should be able to say of the therapist-client relationship, “It’s just you and me, with nothing in-between,” including any theory about the client’s experiencing and what the therapist is supposed to do. There’s absolutely no substitute for Kahneman and Klein’s “skilled intuition.”

Hi Scott,

Great post Scott! I find it so energizing to hear you bring the focus back to the fundamentals and simple but not simplistic ways of working. The work can feel complex which parallels the complex ways that profesdionals describe their work.

I continually find myself getting lost in the complexity of the work, and having to re-member and re-discover how to come back to a simple path forward. I think it signifies the constant realisation of what we don’t have control of in life and therapy, and focusing our attention on the small but potentially significant role we can play.

I really value your research authority on this topic.

With respect.

Mark

I often used Motivational Interviewing in my work with clients in large part because of its emphasis on relationship-building and its use of close careful feedback in training and in follow-up after training. There are thousands of studies supporting its effectiveness.

Yet, even though Motivational Interviewing closely models the approach you are advocating, it does not show a differential superiority to other treatment approaches. The one exception to this that I know of is research suggesting Motivational Interviewing is superior to Cognitive and 12-Step approaches with clients who are more “resistant” to treatment.

What is your understanding of this situation? Why isn’t this or other relationally focused treatments “superior” to others if the therapeutic relationship is so key?

Thanks,

Craig

Hi Scott!

I was just writing about the necessity of being humble enough to invent a new therapy together with every new patient although you have all your theory in the back of your head. I believe that is the only way to do evidence- based therapy, because as I see it evidence of today will not be evidence of tomorrow – we have to lean forward into the future every day – Mind , the gap, or be careful you don´t fall over!