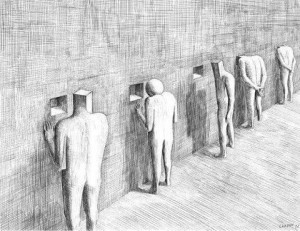

Recognize this? Yours will likely look at bit different. If you drive an expensive car, it may be motorized, with buttons automatically set to your preferences. All, however, serve the same purpose.

Recognize this? Yours will likely look at bit different. If you drive an expensive car, it may be motorized, with buttons automatically set to your preferences. All, however, serve the same purpose.

Got it?

It’s the lever for adjusting your car seat.

I’m betting you’re not impressed. Believe it or not though, this little device was once considered an amazing innovation — a piece of equipment so disruptive manufacturers balked at producing it, citing “engineering challenges” and fear of cost overruns.

For decades, seats in cars came in a fixed position. You could not move them forward or back. For that  matter, the same was the case with seats in the cockpits of airplanes. The result? Many dead drivers and pilots.

matter, the same was the case with seats in the cockpits of airplanes. The result? Many dead drivers and pilots.

The military actually spent loads of time and money during the 1940’s and 50’s looking for the source of the problem. Why, they wondered, were so many planes crashing? Investigators were baffled.

Every detail was checked and rechecked. Electronic and mechanical systems tested out. Pilot training was reviewed and deemed exceptional. Systematic review of accidents ruled out human error. Finally, the equipment was examined. Nothing, it was determined, could not have been more carefully designed — the size and shape of the seat, distance to the controls, even the shape of the helmet, were based on measurements of 140 dimensions of 4,000 pilots (e.g., thumb length, hand size, waist circumference, crotch height, distance from eye to ear, etc.).

It was not until a young lieutenant, Gilbert S. Daniels, intervened that the problem was solved. Turns out, despite of the careful measurements, no pilot fit the average of the various dimensions used to design the cockpit and flight equipment. Indeed, his study found, even when “the average” was defined as the middle 30 percent of the range of values on any given indice, no actual pilot fell within the range!

The conclusion was as obvious as it was radical. Instead of fitting pilot into planes, planes needed to be designed to fit pilots. Voila! The adjustable seat was born.

Now, before you scoff — wisecracking, perhaps, about “military intelligence” being the worst kind of oxymoron — beware. The very same “averagarianism” that gripped leaders and engineers in the armed services is still in full swing today in the field of mental health.

Now, before you scoff — wisecracking, perhaps, about “military intelligence” being the worst kind of oxymoron — beware. The very same “averagarianism” that gripped leaders and engineers in the armed services is still in full swing today in the field of mental health.

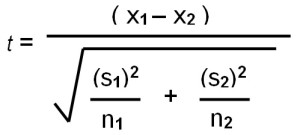

Perhaps the best example is the randomized controlled trial (RCT) — deemed the “gold standard” for identifying “best practices” by professional bodies, research scientists, and governmental regulatory bodies.

However sophisticated the statistical procedures may appear to the non-mathematically inclined, they are nothing more than mean comparisons.

Briefly, participants are recruited and then randomly assigned to one of two groups (e.g., Treatment A or a Control group; Treatment A or Treatment as Usual; and more rarely, Treatment A versus Treatment B). A measure of some kind is administered to everyone in both groups at the beginning and the end of the study. Should the mean response of one group prove statistically greater than the other, that particular treatment is deemed “empirically supported” and recommended for all.

The flaw in this logic is hopefully obvious: no individual fits the average. More, as any researcher will tell you, the variability between individuals within groups is most often greater than variability between groups being compared.

Bottom line: instead of fitting people into treatments, mental health care should be to made to fit the person. Doing so is referred to, in the psychotherapy outcome literature, as responsiveness — that is, “doing the right thing at the right time with the right person.” And while the subject receives far less attention in professional discourse and practice than diagnostic-specific treatment packages, evidence indicates it accounts for why, “certain therapists are more effective than others…” (p. 71, Stiles & Horvath, 2017).

Bottom line: instead of fitting people into treatments, mental health care should be to made to fit the person. Doing so is referred to, in the psychotherapy outcome literature, as responsiveness — that is, “doing the right thing at the right time with the right person.” And while the subject receives far less attention in professional discourse and practice than diagnostic-specific treatment packages, evidence indicates it accounts for why, “certain therapists are more effective than others…” (p. 71, Stiles & Horvath, 2017).

I’m guessing you’ll agree it’s time for the field to make an “adjustment lever” a core standard of therapeutic practice — I’ll bet it’s what you try to do with the people you care for anyway.

Turns out, a method exists that can aid in our efforts to adjust services to the individual client. It involves routinely and formally soliciting feedback from the people we treat. That said, not all feedback is created equal. With a few notable exceptions, all routine outcome monitoring systems (ROM) in use today suffer from the same problem that dogs the rest of the field. In particular, all generate feedback by comparing the individual client to an index of change based on an average of a large sample (e.g., reliable change index, median response of an entire sample).

By contrast, three computerized outcome monitoring systems use cutting edge technology to provide feedback about progress and the quality of the therapeutic alliance unique to the individual client. Together, they represent a small step in providing an evidence-based alternative to the “mean” approaches traditionally used in psychotherapy practice and research.

Interested in your thoughts,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

PS: Want to learn more? Join me and colleagues from around the world for any or all three, intensive workshops being offered this August in Chicago, IL (USA).

- The FIT Implementation Intensive: the only workshop in the US to provide an in depth training in the evidence-based steps for successful integration of Feedback Informed Treatment (FIT) into your agency or clinical practice.

- The Training of Trainers: a 3-day workshop aimed at enhancing your presentation and training skills.

- The Deliberate Practice Intensive: a 2-day training on using deliberate practice to improve your clinical effectiveness.

Click on the title of the workshop for more information or to register.

Dear Scott,

Thank you for all your insights, and the inputs for practicing psychotherapy. It is a real paradigm shift in my daily practice. There would be much to be done here in France, where there are a lot of arguments over which psychotherapy model is best rather than « what’s good for this client? » and the following outcomes…

So thanks again, and keep us posted!

Best regards,

As with adjustable seats in autos, how I ensure I am tracking with my Clients to achieve THEIR outcomes was through questioning and then course correcting when what I proposed did not fit their paradigm. I am never afraid to be corrected by a Client because I know they know more about themselves than I do. My Clients teach me. I learn from them. Psychotherapy is an art not a science. Client attunement is paramount to getting the best outcomes both in session and in total treatment. Client sets the goal mutually with me and we work toward attainment. It’s their goal not mine.

Hello Scott,

This was a great blog (They are all good, but this one was particularly thought provoking). I still wonder (although I should know better by now) why it is so difficult to convince people to change how their systems work and to abandon the “obsession” with “evidence-based practices”. It seems to be pretty clear what the evidence tells us! It probably has to be done on a legislative basis since system-wide change, in this case, may not come from within the field. -Or, universities need to be pushing for this paradigm shift so newly graduated practitioners take it for granted that gathering feedback from clients on a routine basis is the norm, not the exception! Thank you sharing!

I would love to be able to come to your workshops… any chance you will have them a little bit closer to Vancouver?

Thank you from Norway , from a human beeing going to psycotherapy for 6,5 year and ended up depended and questioning my own sanity. I tried to speak up but was not heard. Sites like this and the genuine voice of a therapist who goes right into what is helpfull gives me hope. Thank you again.