What works in the treatment of people with eating disorders? Search around a bit on the internet, or consult official treatment guidelines, and you’ll find cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) listed as the “best-supported” or “preferred” psychological approaches for bulimia, anorexia, and binge eating.

Such recommendations strongly imply such approaches contain ingredients specifically remedial to eating disorders which, when applied, result in superior outcomes. Otherwise, why create the list in the first place?

But what does the evidence actually indicate? While research in mental health rarely results in definitive findings, in the case of eating disorders, the story is different. When it comes to psychotherapy, all methods work equally well. At least, that is the conclusion of the most recent, sophisticated meta-analysis on the subject. However, if history serves as a guide, many will find the latest results hard to swallow.

Back in 2014, an article penned by proponents of the “specific treatments for specific disorders” — aka the “empirically supported” treatments movement — appeared in The Guardian, claiming science had show that some approaches were “better for certain conditions than others,” in particular eating disorders. Citing the tremendous cost to sufferers and the healthcare system, they urged the field to “redouble … efforts to identify … and ensure that the most effective therapies are available to all who need them.”

As I blogged about at the time, I received a ton of email when that article first appeared. “Have you seen the Guardian?” they asked. “What do you make of it?” others inquired. A few messages were downright snarky, even gloating, “Scott, research has finally proven certain approaches are more effective than others. I knew it all along!”

I responded noting that the claims in the article were based on a single study. One. And yes, that one study comparing CBT to psychoanalysis found CBT resulted in superior effects in the treatment of bulimia. Crucially, I pointed out, the authors failed to mention the existence of another, exhaustive investigation available at the time in Clinical Psychology Review—one that used the statistically rigorous method of meta-analysis to review 53 studies of psychological treatments for eating disorders, and found no differences in effect between competing therapeutic approaches.

Four-and-a-half years later, the question of “what works best” in the treatment of eating disorders is being addressed in a brand new study in the top tier journal, Psychotherapy Research. (As of right now, you can read it for yourself for free by clicking here. Be prepared, however, as this is not an opinion piece written in a newspaper, but rather an academically rigorous analysis of the evidence).

What did the authors find? Confirming the results of the prior meta-analysis: (1) any treatment works better than none; (2) real treatments are more effective than sham approaches; (3) and no method works better than any other.

Similar results, have been found across a wide range concerns that bring people into treatment, including trauma, sexual abuse, alcohol abuse and dependence, depression and anxiety.

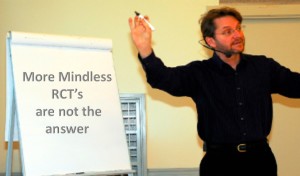

Given the evidence, the question is not whether such results can be trusted. They can. Indeed, they represent the “state-of-the-art” — the best research has to offer. The real problem, then as now, is that such findings do not address the question therapists most want answered, “What can I do to better help my clients?”

To answer this question, we have to recognize a simple fact: therapists live in a fundamentally different world than researchers. We do not deal with groups of people sharing a common diagnosis who are randomized into different treatments. Neither are we are interested in differences in the means response of aggregate group comparisons. We deal with individuals. Confronted daily by their suffering, we want to know how to help the person in our office right now. The problem comes whenever these two worlds are conflated, as advocates of particular treatment approaches are prone to do. It’s then our pragmatic focus make us exceptionally vulnerable to anyone claiming to have discovered “a better way.”

So, what can therapists do to improve their effectiveness?

Simply put: find out if what you are doing is helping your client. Do this by seeking feedback on a formal, session-by-session basis about their progress and experience of the therapeutic relationship–a process known as “Feedback-Informed Treatment” or FIT (you can access two, free, brief and simple-to-use scales by clicking here). A variety of support materials, and 10,000+ clinicians and administrators are available at no cost via the International Center for Clinical Excellence website. Importantly, evidence shows clients of therapists who have integrated FIT into their work are 2.5 times more likely to experience improvement over the course of care.