Therapists want to improve. In the largest, most comprehensive survey conducted to date, 86% of clinicians reported being “highly motivated” to transcend their current level of performance (1).

No wonder the arrival of deliberate practice on the professional scene has attracted so much interest. Always hungry for guidance and direction about helping their clients, most therapists say, “Just tell me what to practice and I’ll do it.” When I tell them that’s the wrong question, confusion often follows.

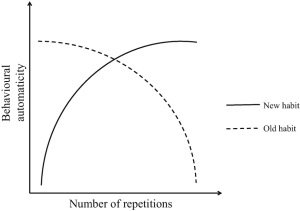

Historically, the mental health professions have never suffered from a shortage of experts ready and willing to tell practitioners what to do to be effective (2, 3). The premise has, and continues to be, practice this method or that technique until proficiency is reached, and professional growth is assured. In the time since the concept was first introduced to psychotherapy in our 2007 article, “Supershrinks,” a series of books and studies have appeared mistaking repetition and rehearsal of particular methods for deliberate practice.

What do practitioners need to do instead?

Prior to embarking on a course of professional development, each must answer the question, “what do I need to target to improve my particular results?” Failing to develop a therapist-specific answer to this question, all but guarantees: (1) clinician effectiveness will remain flat, as has been seen in the field for the past 40 years; or (2) decline, as studies of individual therapist outcomes shows happens, regardless of the amount of time, money and energy invested in learning something new (4, 5, 6).

The process begins with measurement. Over the last two decades, several outcome measurement systems have been developed which provide detailed metrics capable of helping each clinician establish an evidence-based profile of their work. You can download and get started using our tools for free here.

The next step is analyzing the data you accumulate — that is, looking deeply at what, where, and with whom you excel and, more importantly, where you fall short or could make improvements. And let me offer reassurance to anyone whose first response to the words, “analyzing data,” is a combination of terror and traumatic memories from graduate school stats courses. Without exception, the procedures involved are more tedious in nature than mathematically challenging.

Not long ago, I interviewed psychotherapist Michael Harloff about his efforts to identify his “learning edge.” In the video you’ll not only hear the steps he took, and the time involved, but see and obtain a copy of the tool he created to both categorize and mine his results (the payoff was amazing, by the way). If you’ve been gathering data about your clinical performance in the hopes of setting individualized deliberate practice objectives, you won’t want to miss it!