Available evidence leaves little doubt. As I’ve blogged about previously, separating intake from treatment results in:

• Higher dropout rates;

• Poorer outcomes;

• Longer treatment duration; and

• Higher costs

And yet, in many public behavioral health agencies, the practice is commonplace. What else can we expect?

Chronically underfunded, and perpetually overwhelmed by mindless paperwork and regulation, agencies and practitioners are left with few options to meet the ever-rising number of people in need of help. Between 2009 and 2012, for example, the number of people receiving mental health services increased by 10%. During the same period, funding to state agencies decreased $4.35 billion. Not long ago, in my own home town of Chicago, the city shuttered half—50%–of the city’s mental health clinics, forcing the remaining, already burdened, agencies to absorb an additional 5,000 people in need of care.

Simply put, the practice of separating intake from treatment is little more than a form of “crowd management”–and an ineffective one at that.

Adding to the growing body of evidence is a new study investigating the impact of computerized intake on the consumer’s experience of the therapeutic relationship and continuation in care. Not only did researchers find that therapist use of a computer had a negative impact on the quality of the working relationship—one of the best predictors of outcome–but clients were between 62 and 97% less likely to continue in care!

It’s not hard to see how these well-intentioned—some would argue, absolutely necessary—solutions actually end up exacerbating the problem. Money is wasted when the paperwork is completed but people don’t come back; money that would be better spent providing treatment. Those who do not return don’t disappear, they simply access services in other ways (e.g., the E.R., police and social services, etc.)—after all, they need help! The ones who do continue after intake, experience poorer outcomes and stay longer in care, a cost to both the consumer and the system.

What to do?

In addition to pushing back against the mindless regulation and paperwork, there are several steps practitioners and agency managers can take:

- Stop separating intake from treatment

The practices does not save time and actually increases costs. Consider having consumers complete as much of the paperwork as possible before the session begins. The first visit is critical. It determines whether people continue or drop pout. Listen first. At the end of the visit, review the paperwork, filling in missing data, and completing any remaining forms.

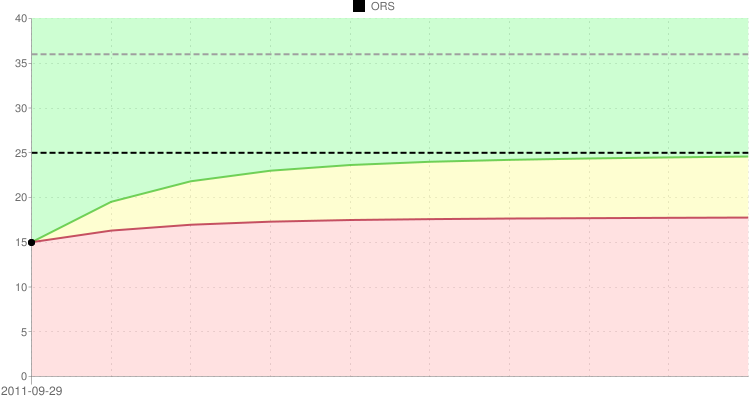

- Begin monitoring outcome

Research to date shows that routinely monitoring progress reduces dropout rates and the length of time spent in treatment while simultaneously improving outcome. Combined, such results work to alleviate the bottleneck at the entry point of services.

- Begin monitoring the quality of the therapeutic relationship:

Engagement and outcomes are improved when problems in the relationship are identified and openly discussed. Even when intake is separated from treatment, feedback should be sought. Data to date indicate that the most effective clinicians seek and more often receive negative feedback, a skill that enables them to better meet the needs of those they serve.

Getting started is not difficult. Indeed, there’s an entire community of professionals just a click away who are working with and learning from one another. The International Center for Clinical Excellence is the largest, web based community of mental health professionals in the world. It’s ad free and costs nothing to join.

Sign up for the ICCE Fall Webinar. You will learn:

- The Empirical Basis for Feedback Informed Treatment

- Basics of Outcome and Alliance Measurement

- Integrating Feedback into Practice & Creating a Culture of Feedback

- Understanding Outcome and Alliance Data

Register online at: https://www.eventbrite.ie/e/fall-2015-feedback-informed-treatment-webinar-series-tickets-17502143382. CE’s are available.

Finally, join colleagues and friends from around the world for the Advanced and FIT Supervision courses are held in March in Chicago. We work and play hard. You will leave with a thorough grounding in feedback-informed principles and practice. Registration is limited, and the courses tend to sell out several month in advance.

Until then,

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D. Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)