When it comes to professional development, we therapists are remarkably consistent in opinion about what matters. Regardless of experience level, theoretical preference, professional discipline, or gender identity, large, longitudinal studies show “learning from clients” is considered the most important and influential contributor (1, 2). Said another way, we believe clinical experience leads to better, increasingly effective performance in the consulting room.

When it comes to professional development, we therapists are remarkably consistent in opinion about what matters. Regardless of experience level, theoretical preference, professional discipline, or gender identity, large, longitudinal studies show “learning from clients” is considered the most important and influential contributor (1, 2). Said another way, we believe clinical experience leads to better, increasingly effective performance in the consulting room.

As difficult as it may be to accept, the evidence shows we are wrong. Confidence, proficiency, even knowledge about clinical practice, may improve with time and experience, but not our outcomes. Indeed, the largest study ever published on the topic — 6500 clients treated by 170 practitioners whose results were tracked for up to 17 years — found the longer therapists were “in practice,” the less effective they became (3)! Importantly, this result remained unchanged even after researchers controlled for several patient, caseload, and therapist-level characteristics known to have an impact effectiveness.

Only two interpretations are possible, neither of them particularly reassuring. Either we are not learning from our clients, or what we claim to be learning doesn’t improve our ability to help them. Just to be clear, the problem is not a lack of will. Therapists, research shows, devote considerable time, effort, and resources to professional development efforts (4). Rather, it appears the way we’ve approached the subject is suspect.

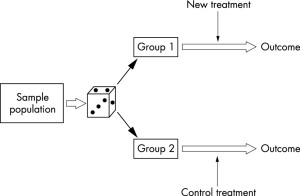

Consider the following provocative, but evidence-based idea. Most of the time, there simply is nothing to learn from a particular client  about how to improve our craft. Why? Because so much of what affects the outcome of individual clients at any given moment in care is random — that is, either outside of our direct control or not part of a recurring pattern of therapist errors. Extratherapeutic factors, as influences are termed, contribute a whopping 87% to outcome of treatment (5, 6). Let that sink in.

about how to improve our craft. Why? Because so much of what affects the outcome of individual clients at any given moment in care is random — that is, either outside of our direct control or not part of a recurring pattern of therapist errors. Extratherapeutic factors, as influences are termed, contribute a whopping 87% to outcome of treatment (5, 6). Let that sink in.

The temptation to draw connections between our actions and particular therapeutic results is both strong and understandable. We want to improve. To that end, the first step we take — just as we counsel clients — is to examine our own thoughts and actions in an attempt to extract lessons for the future. That’s fine, unless no causal connection exists between what we think and do, and the outcomes that follow … then, we might as well add “rubbing a rabbit’s foot” to our professional development plans.

So, what can we to do? Once more, the answer is as provocative as it is evidence-based. Recognizing the large role randomness plays in the outcome of clinical work, therapists can achieve better results by improving their ability to respond in-the-moment to the individual and their unique and unpredictable set of circumstances. Indeed, uber-researchers Stiles and Horvath note, research indicates, “Certain therapists are more effective than others … because [they are] appropriately responsive … providing each client with a different, individually tailored treatment” (7, p. 71).

What does improving responsiveness look like in real world clinical practice? In a word, “feedback.” A clever study by Jeb Brown and Chris Cazauvielh found, for example, average therapists who were more engaged with the feedback their clients provided — as measured by the number of times they logged into a computerized data gathering program to view their results — in time became more effective than their less engaged peers (8). How much more effective you ask? Close to 30% — not a bad “return on investment” for asking clients to answer a handful of simple questions and then responding to the information they provide!

What does improving responsiveness look like in real world clinical practice? In a word, “feedback.” A clever study by Jeb Brown and Chris Cazauvielh found, for example, average therapists who were more engaged with the feedback their clients provided — as measured by the number of times they logged into a computerized data gathering program to view their results — in time became more effective than their less engaged peers (8). How much more effective you ask? Close to 30% — not a bad “return on investment” for asking clients to answer a handful of simple questions and then responding to the information they provide!

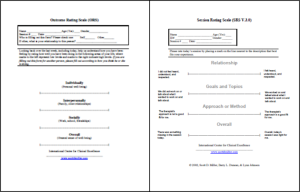

If you haven’t already done so, click here to access and begin using two, free, standardized tools for gathering feedback from clients. Next, ioin our free, online community to get the support and inspiration you need to act effectively and creatively on the feedback your clients provide — hundreds and hundreds of dedicated therapists working in diverse settings around the world support each other daily on the forum and are available regardless of time zone.

And here’s a bonus. Collecting feedback, in time, provides the very data therapists need to be able to sort random from non-random in their clinical work, to reliably identify when they need to respond and when a true opportunity for learning exists. Have you heard or read anything about “deliberate practice?” Since first introducing the term to the field in our 2007 article, Supershrinks, it’s become a hot topic among researchers and trainers. If you haven’t yet, chances are you will soon be seeing books and videos offering to teach how to use deliberate practice for mastering any number of treatment methods. The promise, of course, is better outcomes. Critically, however, if training is not targeted directly to patterns of action or inaction that reliably impact the effectiveness of your individual clinical performance in negative ways, such efforts will, like clinical experience in general, make little difference.

If you are already using standardized tools to gather feedback from clients, you might be interested in joining me and my colleague Dr. Daryl Chow  for upcoming, web-based workshop. Delivered weekly in bite-sized bits, we’ll not only help you use your data to identify your specific learning edge, but work with you to develop an individualized deliberate practice plan. You go at your own pace as access to the course and all training materials are available to you forever. Interested? Click here to read more or sign up.

for upcoming, web-based workshop. Delivered weekly in bite-sized bits, we’ll not only help you use your data to identify your specific learning edge, but work with you to develop an individualized deliberate practice plan. You go at your own pace as access to the course and all training materials are available to you forever. Interested? Click here to read more or sign up.

OK, that’s it for now. Until next time, wishes of health and safety, to you, your colleagues, and family.

Scott

Scott D. Miller, Ph.D.

Director, International Center for Clinical Excellence